|

Timeline Hypotheses Evidence

Most of this

material is included here on Harpguitars.net, and includes the Knutsen

Patents, the Livermore and Gaskin harp mandolin patents, the

Knutsen/Dyer flyer, the complete BMG advertising run, and the many

instruments themselves, including the critical label information.

Unfortunately, some of the latter data may be faulty due to misread, mis-communicated,

or poorly photographed or inspected labels.

Before attempting

an understanding of the material below, I would

highly recommend reading the Knutsen and Larson books,

re-familiarizing yourself with the

patents,

continuing with the

overview of models,

and then studying the complete

BMG advertising

run.

Next is my

original 2010 list of conflicting or unproven information and

evidence. Happily, some of this has since been solved.

Next is my

original 2010 list of conflicting or unproven information and

evidence. Happily, some of this has since been solved.

A) The Cadenza ad of December, 1901 showing a Type 1

Dyer Symphony harp guitar

B) The various harp guitars of Type 2 design that have

very low serial numbers, along with hard-to-read numbers

C) The mention of a “1906 model” referring to the Type 2

design introduced in December, 1904

D) The handwritten “1909” of Stephen Bennett’s harp

guitar with serial number 669, the claim of a patent on all

post-Knutsen Dyer labels, and Knutsen’s claim of “sole patentee” on

his own labels

E) The unknown date of introduction of the “lower bass

point” harp guitars built by both Knutsen and the Larsons

F) The use of “Style 3” for the Type 3 design, whereas

“Style 4 through 8” are used for ornamentation designations on the

Type 2 design, while Style “1” and “2” have never turned up

G) Duplicate serial numbers

What

follows is my 2010 discussion of the bullets above. I have mostly left

his intact (for archival purposes),

but include new

text in red where I have resolved or changed my opinion.

| A) The 1901

Cadenza ad

This curious ad conundrum was finally put to rest in 2024 when harp

guitarist Randall Sprinkle shared with me a cryptic historic photo which

I tracked down to the Wisconsin Historical Society, who subsequently

licensed it for our use and provided the critical high-resolution image.

You can read the story here.

The reason it proved frustrating for the last dozen-plus years is

discussed below (now redundant, I’m archiving all these discoveries and

updates as they happened, for history’s (and my) sake:

The first

ad that Dyer ran depicting a harp guitar appeared in The Cadenza in

December, 1901. It shows a frustratingly stylized woodcut of a

Knutsen-style (Larson’s Dyer Type 1) Symphony harp guitar. The headstock

appears to represent a clean, slotted, Larson-made headstock, though the

neck itself is offset significantly to the treble side as in a Knutsen.

The depicted 10th fret marker (rather than 9th)

was used by both Knutsen and the Larsons (though not consistently). The

neck heel could be an attempt at depicting either the traditional Larson

heel or the "bulgy" butt-joint heel of early Knutsens like HGT15 and

HGT1. This same ad ran all the way through November, 1904 – with one

curious five-month gap - when it was immediately replaced by a similar

ad with a woodcut of the Type 2 version. Our key questions:

Was Dyer still distributing Knutsen instruments through 1904? Or did

this ad depict the first of the Larson-built, Knutsen-licensed Type 1

instruments? Or yet another possibility – that the ad covered both

Knutsen and, later, Larson instruments? |

|

|

Bob and I originally agreed that the woodcut

represented a Larson-built Symphony harp guitar.

The artist was presumably copying an actual instrument (or a

picture of one), and the "Waverly-style" tuners on the slotted

headstock seemed a dead giveaway. Knutsen

simply never did this on any known Symphony specimens.

In fact, by 1902, he would permanently switch to a solid

headstock with geared tuners. Moreover, by 1902, Knutsen had

abandoned this model, experimenting with his very inconsistent

“Evolving” Symphony harp guitars for the next few years.

We further interpreted the illustration as depicting a neck heel

– which Knutsen never did, but was typical of Larsons.

The offset neck I attributed to shoddy draftsmanship.

Finally, we had to acknowledge that there are no known specimens

of Knutsen-built instruments with a Dyer label.

And yet….not being able to fit the serial numbers into a timeline

implied by all of the ads, I’ve taken a new, harder look at this

particular ad. |

|

For one thing, rather than ignore the neck placement and

crude neck heel, let’s consider them.

To my eye, the heel looks a

lot closer to the Knutsen bulge – rare, but seen on several early Symphony instruments (see photo)

– than a Larson-style heel (photo).

If we are to take the neck

at face value, then it clearly represents Knutsen’s significantly

offset neck, which is like no other.

On the Larson’s similar Type 1 the neck would be barely offset

to the right (ending up slightly offset to the bass side on the Type

2s). Taking

the headstock and tuners at face value, we clearly see a Larson.

The result: It does not add up.

If we take everything in the drawing literally, we end up with a

chimera of an instrument that does not exist.

So

how do we decipher it?

An alternative scenario that I find perfectly reasonable is that

the engraver copied an image of a Knutsen

harp guitar, and when they got to the difficult-to-resolve mess of

Knutsen’s early headstock – with its crude individual tapered

“slots” - they simply borrowed a design from a more traditional

guitar (virtually any early 6-string image lying around would have

sufficed). This scenario

would then negate the argumentative clue above about Knutsen switching

to a solid headstock, as the ad drawing was completed before that time. If

true, the fact that Dyer didn’t then bother to change the image when

the Larsons finally did produce this model could be explained by the fact that the image

already “looked like” their version.

Both makers had fully bound versions of this design, by the way.

We now know that Dyer was already distributing Knutsen’s own

labeled instruments around 1900, without any apparent qualms – so

there is no real reason to be alarmed by the lack of Dyer-labeled

Knutsens distributed for another couple of years. The

1901 Cadenza ad advertising (Knutsen) “Symphony Harp Guitars” as

being sold by Dyer would not be unusual.

Whatever you (or I) might think of the two scenarios above, let’s

call this a draw for now. |

Knutsen

|

|

Dyer

|

|

But another problem with this ad is that it ran

for twenty-one consecutive months, then after a

five-month hiatus, returned for another ten months.

That’s a full three years of production for a Dyer model of

which there are only four specimens known! One

caveat about the 5-month interruption: they ran a new ad for

their line of strings for four of these months, so it is

possible, that it wasn't so much a "harp guitar hiatus" as a

"new promotion" of a new product (Sterling Strings). And yet -

it seems more than strange that Knutsen's Symphony harp guitars

from this same period outnumber the Larson Type 1 Symphony by

over 20 to 1, when Knutsen did little or no

advertising. A reasonably logical answer to this dilemma might

be to consider my alternative theory of the previous paragraph –

that the 1901 image was in fact representing a Knutsen

– and that the six-month gap (September, 1903 through February,

1904) possibly coincides with a period where Knutsen was “let

go” and the Larsons were hired and gearing up to copy the

Knutsen model. Knutsen was indeed experimenting with many

different features in 1902 and beyond, and his quality and

aesthetics were only getting worse in general – so Dyer would

have understandably become fed up by this point. It does

seem strange that Dyer would simply re-use the old Knutsen ad

and not roll out a big new campaign, but there is a similar and

even more inexplicable lack of any sense of excitement when they

unveil the Type 2 just nine months later. I thus don’t see

any of this as a deal-breaker in the clue department.

Update, October 2011:

Now that a fourth Type 1 specimen has been found – the first

with a legible Style number (“5” – more on this significance

below), we finally have some better clues. Specifically, that

two of the four known Type 1 serial numbers are now known – 125

and 127 – which we believe equates to the 25th and 27th

instrument built. With the lowest confirmed serial number of the

Type 2 being 140, this would suggest that somewhere between 27

and 39 Type 1’s were produced. Update, March 2020: A fifth Type

1 specimen - the earliest so far - has the Knutsen-signed label

with serial # 120. The Style may again read 5 - in this case, a

small "05." It too has the simple appointments of the Type 2

Style 4.

Bottom line: When taking not only the number of surviving

specimens into account, but also trying to fit the early Dyer

serial numbers into these two opposing scenarios, I find myself

consistently favoring a Knutsen-then-Larson scenario for the

December, 1901 through November, 1904 “Type 1” Cadenza ad. (Just

remember that I could be completely wrong)

Counterpoint:

Bob recently pointed out the question of the Maurer Company

which August Larson bought with other investors in 1900. He

wonders if this could have been a business venture

specifically to be able to handle a new Dyer contract. I

also find this timing intriguing – however I’m not too inclined

to weigh in on it, simply because of my stance above (the low

numbers of instruments found). Nevertheless, this newly-formed

company certainly could have been a key factor in the success of

the Dyer line. Something Bob has never really explored and

shared with us until recently is the fact that the new Maurer

Company might very well have had an unknown quantity of

additional employees to assist in production. They could easily

have employed workers from Maurer’s factory, for example. It is

also not known whether August’s partners (Longworthy and Lewis)

were luthiers or just businessmen. The Larsons were a legendary

“two-man shop” all right – but the key word is “legendary.”

That lore came from Bob’s family members much later, and they

may have known nothing of the early Maurer years. Here is

Bob's latest write-up for us on the Maurer Company:

|

The Dawn of Maurer & Co.

by Robert C. Hartman

Robert Maurer was a music teacher and importer of

musical instruments, the first published notice

being in 1886. The year of 1894 is the probable date

of his first factory production using the firm name

of Maurer Mandolins and Guitars. In 1897 the name

was changed to Maurer & Co. and he produced the

Champion brand of guitars and mandolins, probably

concurrently with some branded Maurer. (I have

recently found “New Model” Maurer branded mandolins

with very early features including a different

shaped peghead (larger, squared-off) than in any of

the later styles

In March of 1900 Maurer sold the company to August

Larson and two investors and/or luthiers for $2,500.

I would think for that tidy sum the purchase would

have included the whole operation of Maurer & Co.

including remaining inventory of instruments. This

statement leads to the possible answer for the very

few circa dated instruments made in those first few

years. It also raises the question, what were their

serial numbers? It is just as possible that my circa

dates for Larson built Maurer instruments should be

earlier.

It is my belief that the brothers built mandolins,

guitars and harp guitars for Regal Mfg. in

Indianapolis during the span from 1901 to 1904,

which would add to their production. These

instruments had their own serial number series so

they did not mingle with the Larson system, which

appears to have started at 101. |

New Bottom Line:

Obviously, Bob won that one! But it took him 14 years and my own

article and conclusions to make it happen!

|

|

B) Type 2 Dyer harp guitars with very low serial numbers and

hard-to-read numbers

It is now clear that the Larsons built the Type 1

harp guitar first, and then created the Type 2, abandoning

Knutsen’s design. That’s not to say that there couldn’t have

been some overlap. So, you would think that as we collected

serial numbers, the Type 1s would be found with very low

numbers, and the Type 2s would generally have higher numbers

than the highest Type 1. If only it were that simple!

One problem that plagues us is indirect evidence. There

are a lot of entries on Bob’s old list (and even some on my

later list) that came from a questionable source. Even when we

know the source, if we don’t see a decent photograph

of the label at the very least, then we are just taking

their word for it. We have long since learned that faded ink or

pencil and/or sloppy handwriting can easily cause a number to be

misread, and even if legible, someone’s hasty scribble and

subsequent letter or email to us of their provenance can yield

errors.

|

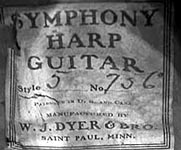

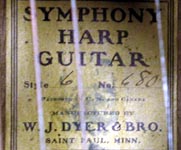

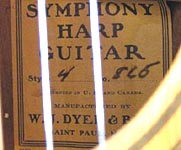

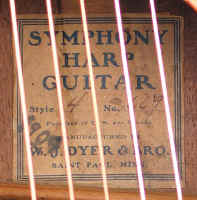

Here is an example of difficult to read Dyer labels:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note the handwritten number 5 and 6 in the series,

starting from the left. Personally, I cannot judge how many of

these serial numbers are in the same hand or penned by different

individuals. The label on the right has been in my folders for

years, but never added to our serial number list. Now I remember

why. I originally couldn't tell if it was "845" or "865." Can

you? I wasn't sure if that was a second poorly-written "4" or

what. I thought the last digit must be a "6." Now that I've seen

many written sixes, I realized that that must be "6," meaning

the last digit can't be another six, but something else -

a "5" with the loop closed (ink bleeding or penmanship). This

is just one example of problematic Dyer labels.

Thus, a serial number that we take in good

faith - but that may actually be a gross error - is

extremely detrimental to our research. For example, #108 is

credited to a Type 2 Dyer that appeared on eBay in the distant

past. We do not have photos from the ad, nor know if any were

even included. We certainly can’t take an eBay seller’s word for

it – from what we now know, the number was almost certainly 608

or 708. As this suspect number might otherwise make or break our

entire timeline and serial number theories, it becomes extremely

problematic – dangerous even. While acknowledging that there is

a real, if very slim, chance that it is correct, we

should certainly make note of it but not use it as

evidence (I long ago removed it from the list for this

reason). Similarly, other Type 2 numbers may or may not

be accurate.

Bottom line:

Help us by submitting clear photographs of your labels. Try

illuminating with a black light in the dark if they are hard to

read.

|

|

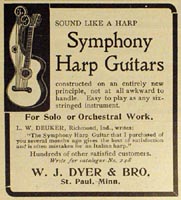

C)

The

November, 1906 ad that declares “1906 model” of the Type 2 design

introduced in 1904

|

|

This one makes absolutely no sense. Originally, having seen only

later ads that mentioned the 1906 model, and we assumed it meant

that the Type 2 was introduced in 1906. But we later learned

that the Type 2 appeared in the Cadenza ad of

December, 1904. It arrived with no fanfare, no major

announcement, no special “press release” to the Cadenza editors

that this was a major new design or achievement. Just a similar

crude woodcut and a claim that it was “constructed on an

entirely new principle.” This could be taken different ways

– from a simple advertising boast to an interpretation that it

refers to either the new builders (the Larsons) or the new

design. Note that it also includes the first customer

testimonial, which may or may not have been in reference to

either a Knutsen Symphony or Larson-built Type 1 instrument. |

|

|

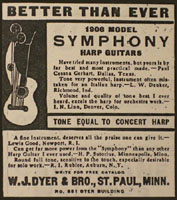

Then, in November, 1906 – nearly two years later –

Dyer announces the “better than ever” “1906 model.” Yet it

features just a poor resolution copy of the exact same woodcut

from 1904 (along with a total of five testimonials). Again, this

could just be advertising hyperbole (“let’s pretend it’s a new,

updated instrument!”), or it could have some critical,

as-yet-unknown significance to our research. The sixth

sub-bass string wouldn’t show up for another couple years, and

we’ve seen no significant Larson design features from the early

to the later instruments. I honestly can’t think of anything

other than maybe some new construction feature (laminated

bracing experiments, etc.?). Perhaps that is where we should be

looking – a switch in bracing patterns or quality.

Multiple-specimen Dyer repairmen like Kerry Char have long

noticed differences in braces: specifically, Kerry has seen the

X braces in maple rather than spruce, and several have seen the

spruce/rosewood/spruce laminated braces – but we think that that

latter feature coincides with the more expensive Style 7 and 8

and not necessarily dependent on year built. Certainly, more

data is needed. |

|

|

Curiously, in January, 1907, a Dyer ad appeared in the

American Music Journal, stating "1907 Symphony Harp Guitars"

(Noonan, 2009). I have yet to examine the image, but I suspect

there will be nothing surprising. This new finding makes me

think that they were just updating the "model" with the new year

when the first ads of that year are placed.

Bottom line:

I originally thought this was a tantalizing and unanswerable

clue. Now, with the "1907 model" example on top of the original

"1906 model" example, I would wager that it actually has

no significance. For now, we can ignore it.

|

| D) The

handwritten “1909” on the label of serial number 669 |

|

We get a lot of “provenance” from unverifiable sources. Often it

is a relative who swears that a handed-down instrument was

purchased in some specific year – which usually turns out to be

unlikely or impossible. Other times there are written notes from

a previous owner – either a scrap of paper inside the case or

something added to the label. A simple rule is to consider

this type of information as a possible clue, weighing both its

feasibility and integrity, but to never accept any of it as

“evidence.” Such is the case here. On Dyer harp guitar #669

– once circa dated 1914 in Bob’s system – there is a handwritten

“1909” on the label. As I discuss in an

article on this instrument,

it may or may not have been purchased new, but with all things

considered, has a good 50/50 chance or more of being true. While

it is not verifiable “proof,” I have always thought it was worth

considering, and now take it “on faith.” |

|

|

For it to be true, of course, we would have to A)

discard Bob’s old timeline and, B) come up with a completely new

dating and serial number system that reasonably placed #669 in

1909, while fitting what facts we have. So, to point “A” - we

would first need to determine if there was logically a way to

abandon the current system, which places the theoretical

#601 after February, 1912, when Knutsen’s 14-year 1898 design

patent expired. This logically deduced scenario had been a

“fact” during the entire duration of our decades of research

into Knutsen and the Larsons – adhered to by Bob Hartman, Noe

and Most, and myself. But we never had all the evidence, just

the reasonable logic of the theory. We do have the

findings of Knutsen co-author Tom Noe from his exhaustive search

at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, which may (or may not)

have specific bearing on the case – they “prove” some things but

not others. Regardless, I was increasingly frustrated by all the

Knutsen and Dyer provenance that didn’t seem to fit the existing

1912 theory.

So, playing “devil’s advocate,” I first asked

myself if there was a way Dyer could have obtained the rights

to, or ownership of, Knutsen’s 1898 design patent before

it expired in 1912. Unfortunately, the bottom line is, yes,

this could have occurred, but according to Tom Noe,

did not occur – all of which I will explain next

(with good news at the end!).

I posed specific questions to both Tom Noe and

Dyer owner and law professor John Thomas. Their answers were

very illuminating.

Q: Could a 14-year design patent be “renewed” or extended?

TN: Patent terms are not extendible or renewable. 35 USC

154. Trademarks and copyrights can be renewed, but patents

cannot be. When a design patent application is filed, the

patentee selects a term of 3-1/2, 7, or 14 years, and pays an

application fee appropriate to the term selected. Note on the

two Knutsen patents that they state "Term of patent 14 years."

Q: Could two individuals or businesses share this patent?

JT: Yes. The patent holder can license others to use it.

(so “share” only in the sense that both are allowed to market an

item under the contract – but one is a patentee, the other only

a licensee – GM)

TN:

(Since) a licensee does rely on the patent owner to enforce the

patent if an infringement occurs, it would be reasonable for

Dyer to claim that the guitar was protected by a patent.

Q: Would there be a record of the

Dyer license?

TN:

There is no requirement to record licenses. They are basically

contracts.

Q:

Would a patent holder

continue to use old labels on instruments to imply the old

patent is still valid well past the legal period?

JT:

Yes. Beyond the Knutsen and Dyer examples, there have been

others.

TN:

There is no legal requirement to remove "patented" or patent

numbers once the patent expires (this is why we see "C.

Knutsen's Patents" on the New Hawaiian Family label long after

the expiration of the only patents he had). (This) raises the

question of why isn't a patent owner committing fraud by not

taking "Patented" or a patent number off the product. The

answer to that is: #1) saying the product is patented is true

(falsity is an element of fraud), and #2) it would place an

undue burden on a patent owner to recall every product with a

patent number on it.

Q: What about the licensee (Dyer)?

TN: A licensee merely has a right to use (infringe) a patent.

When the patent expires, anyone can use the patent subject

matter. I suppose that Dyer could still say that the design was

patented, but couldn't rely on Knutsen for enforcement purposes.

Q: What does “sole factors” mean on the new September, 1908

Dyer ad?

JT: In this context, I'm confident that "factor" means agent.

From

www.dictionary.com:

5. a person who acts or transacts business for

another; an agent.

6. an agent entrusted with the possession of goods to be

sold in the agent's.

It's not a use that one hears these days, but it crops up in old

business law cases. Dyer & Bro. were advertising that they were

the exclusive agents for selling (this) harp guitar. They used

the plural because the company was "W.J. Dyer & Bro."

TN: Yes, “sole factors” means they were the only agents selling

Dyer guitars.

And the $1,000 question…..

Q: Could a (design) patent be transferred back in 1906?

JT: Yes. From the enactment of the first patent act in 1790,

patents have been considered intellectual property that can be

transferred, licensed, etc.

TN: (Yes, but)

the law requires that

any transfer of patent rights be recorded in the PTO, both in

ownership records and on the file jacket. The transfer of ownership records

don't exist. So, Dyer was a (only a) licensee until 1912…since

Knutsen's patents expired by 1912 (14 years from 1898 on the

second Knutsen design patent), there were no longer any rights

to own.

I pressed Tom on how certain he was, as my whole

“theory” may well have rested on this. He provided further

details of his search and his qualifications for same, and

indeed, the case seems to be closed.

TN: A transfer of ownership of patent rights is known as an

"assignment." The PTO maintains assignment records - drawers

and drawers of them because most patents were assigned to

companies by employee-inventors who had to as a condition of

employment. Even a sale of a patent from one company to another

is an assignment. If a company acquires another company, all

the patents in the acquired company's portfolio have to be

assigned because failure to assign with a period of time results

in an unenforceable patent. If you have a patent number, you

can go to the assignment records and find out who the owner is.

I did that, so I know.

In the last five years of my corporate practice, I was

Intellectual Property Counsel for Danaher Corporation. Among

other duties, I was a member of Danaher's acquisition due

diligence team evaluating patent and trademark portfolios of

target companies to ensure that rights hadn't expired and that

there were no defective assignments. I only mention this

because I spent hours going through assignment records and was

quite proficient at it.

Without an assignment, it is fraud for another, including a

licensee, to claim ownership rights in a patent because it

is a false claim with intent to deceive the public.

So there you have it. It appears that Dyer did

not take over the Knutsen patent prior to its expiration in

1912.

Tom has blown my entire theory…or has he…?

Not at all.

I realized that I was

exploring a “patent transfer theory” not just in hopes of moving

up the 600-series labels (and all Dyer dates) but at the same

time to explain why the “Patented in U.S. & Canada” remained on

Dyer instrument labels so far beyond the 1912 expiration date.

(My “patent extension” question was for this same reason).

Since it felt like a related clue I was focused (and stuck) on

this theory. In any event, based on Tom’s answers above, the

latter question remains unanswerable with specifics, but perhaps

simple overall – Dyer was in a gray area and chose to just

continue using pre-1912 labels that included “Patented.” The

law allows the patentee to do so, a licensee might very well

gamble on the same “scare tactics.” As there is no other

rational or legal explanation, and this did take place,

what other answer is there?

But wait a minute, you’re saying – Dyer didn’t

continue a label in 1912, they switched! (from

the Knutsen-signed label to the standard Dyer label)

Ah hah!

Wrong. They had already switched labels much earlier. Assuming

this is true, wouldn’t it better fit with Tom’s explanation of

patent law above for Dyer to have continued with a pre-existing

label (burden of recalling labeled products, etc.)? As opposed

to fraudulently creating a brand new label in 1912

after the Knutsen patent expired…which again claimed

“patented.”…? Both options involve a gray area of patent

law and marketing, but with the “1912 new label” option

appearing so much less tenable, it (to me) bolsters the idea

that Dyer had to have switched labels earlier.

But how?

I can think of many reasons why Dyer would

have done this, and how most of the clues better fit this

timeline, and even how it all jibes with what we know of

Knutsen. As to how, I simply assumed “Why not? What do

we imagine might have prevented such a simple and obvious

event?” I just needed to make sure that it could have

happened.

So, a final email to Tom Noe, patent expert,

Knutsen expert…

Q: Tom, the final $10,000 question: Is there any reason to

think, or insist, (or have legal basis for) that Knutsen had

to continue to sign the Dyer labels for the full ten or so

years of the license?

I also included for Tom a re-cap of some pertinent

facts:

1.

Knutsen’s applicable patent was in effect from 1898 to Feb 15,

1912.

2.

Dyer licensed this patent from Knutsen starting sometime between

1901 and 1904 (we now know this was

1901)

3.

Dyer printed up labels, which were sent to Knutsen, who signed

them and returned them. These were sent to the Larsons, who

entered serial numbers and installed them in the Dyer

instruments.

4.

All of these labels have serial numbers only in the 100 or 200s.

5.

When Dyer switched to a NEW label

- one without Knutsen's signature - the numbers jumped to 600.

6.

There is no record of Knutsen transferring his patent to Dyer.

Could not the licensing contract simply have been revised so

that Knutsen's signature was not necessary?

TN: There is no legal requirement that Knutsen had to sign

labels, except by contract. Of course, we have no written

contract so we don't know exactly what the arrangement was. But

the fact that the first few labels were notarized tells me that

Knutsen didn't trust Dyer initially, and relaxed a bit as time

went by and subsequent labels were signed but not notarized. It

is really unusual for a licensor to sign labels or products. I

think this was Knutsen's way of keeping track of royalties, at

least at first.

One possibility is that Dyer negotiated a paid-up license

so that the parties didn't have to deal with labels/instruments

on a piece-meal basis. (Regarding the gap between Dyer serial

number series) it could be that Knutsen initially signed 500

labels, 300 of which were returned when some new arrangement was

reached. So Dyer designed a new label, and started with serial

number 601. That’s one scenario.

Bottom line: your theory holds water. By the way, paid-up

patent licenses are quite common. What that means is that for

some agreed-upon royalty figure, the license is paid up for the

term of the patent. It eliminates all the reporting, paying

ongoing royalties, and having the licensor looking over your

shoulder.

And so, once again, there you have it. Understand

that we don’t have proof that such a thing occurred.

But also understand that, similarly, we don’t have any proof

(and little reason to continue to believe) that the

Knutsen-signed label continued all the way up to the expiration

of his patent in 1912.

I don’t know how simple this seems to you, or how

long it has taken you to read, absorb and ponder. It has taken

me years, months, weeks, and now many dozens of hours to rewrite

for the hundredth time – so I know it’s complicated and

convoluted, but I hope the reader considers that I’m on to

something.

Regarding Tom’s interesting speculation above

about the labels jumping in sequence, it might make sense if

these “500 labels” were all serialized, but they weren’t – they

were left blank for the Larsons to fill in. (Update, Sept,

2011: though now I’m wondering that – since the red

pencil/ink of Knutsen’s signature and the Style and Serial

numbers seem to match up, that Knutsen didn’t possibly do all

that himself…?) In any event, I’ve studied American fretted

instrument history long enough to conclude that maker’s serial

numbering systems are often convoluted and arbitrary.

Now, using the above premise, I’ll re-examine the

Knutsen/Dyer timeline.

We know that Knutsen signed the earliest

Larson-built Dyer harp guitars, and that the U.S. and Canada

patent referred to on the label was his (Knutsen’s c.1899 labels

also listed “England”). We can thus safely say that there

was a licensing agreement between Dyer and Knutsen in this

period, which presumably started when Dyer stopped distributing

Knutsen instruments and instead commissioned the Larsons to

build a better version. This must have been in either

mid-to-late1901, as evidenced by the Emory Bennett photo

discovery.

At this point, with the Larsons building

substantially more professional instruments, what if Dyer wanted

to completely distance himself from Knutsen, whose name was

still on the labels? Might not Dyer’s customer get the

impression that Knutsen built their instrument since he signed

it? Dyer would never subsequently credit the deserving Larsons

for their work – wouldn’t he have been even more reluctant to

have Knutsen’s name on the label?! Remember that this would

have been going on for a full ten-plus years during the height

of Dyer’s Cadenza ad campaign.

As stated above, I find it much more likely that

Dyer convinced Knutsen (with financial incentive or otherwise)

to re-negotiate their licensing contract. If such an event

occurred, it would not take effect until mid or late 1906 at the

earliest, and mid-1908 at the latest

(Note: I’ve now placed the specific Dyer events at mid-1908),

and here is what would have theoretically happened:

Knutsen would

stop signing Dyer labels and the new Dyer labels would be

issued.

The “600” series

of serial numbers for harp guitars would begin

(this almost certainly coincided with the label change).

Knutsen would

stop using “Symphony” on his labels, while Dyer continued

using it (this is a known fact, with an

approximate date of this very period. Specifically, circa 1906

he went from “Sole Patentee of the Symphony Harp Guitar with 11

Strings” to “Sole Patentee of the Harp Guitar with 11 Strings.

The theoretical reason being that Knutsen has now

licensed the exclusive use of the “Symphony” name to Dyer.

Knutsen would

still claim “Sole Patentee” on his labels

and Dyer would claim “Patented

in the U.S. & Canada” (these are both facts: for Knutsen,

the approximate dates of 1906/1907 through 1913/1914 for this

label feature are fairly accurate, while the Dyer date is the

unknown.

Knutsen would

begin making only his “lower bass point” (a pointed

flare on the lower bass bout) and “double point” harp guitars

(this is a fact, with an approximate date of this very period).

Many of these would be shorter ¾ scale instruments.

The Larsons

would also build a “lower bass point” harp guitar with a short

scale.

I had dubbed this a “Type 3” Dyer, and by complete coincidence

it was also labeled a “Style 3.” It was built right at the

start of the label change, as every specimen found with a label

has a serial number in the very low 600’s (this is a fact,

though the date of this label change is unknown,

though I have now moved it to mid-1908).

It is not known who copied who on this design

(presumably the Larsons copied Knutsen),

but it is clear that Knutsen built them from circa 1906/7 to

1913/1914, but not beyond, and that the Dyer version appears to

have been only made for a very short time coinciding with the

low 600 serial numbers.

Dyer would state

“Sole Factors” on their ads beginning in September, 1908

(this is a known fact. However, I no longer think it relates to

the new license or new exclusivity of the “Symphony” term

[though it may]. It more likely means that Dyer was merely the

“sole agent” for selling Dyer harp guitars.

Dyer would also

introduce a harp mandolin (this is a fact –

once believed to have occurred in the fall of 1908, but now known to

have occurred in late 1907).

OK, so are there any logistical problems with any of these eight

theoretical events?

No. Bullet #4 is fully covered by Tom Noe’s

answers above. I was always stumped by this issue: How could

both Knutsen and Dyer claim that their harp guitar was

protected by the patent at the same time – with Knutsen even

claiming “sole patentee”? As Tom explained, Knutsen

was still the "sole patentee" – he never transferred it, so

remained the sole owner of the patent for its fourteen-year

duration - and Dyer was still a licensee, allowed to claim

patent protection for their licensed product – with or without a

signature from the licensor. As far as public perception,

Dyer’s customers would now no longer be aware of this "Knutsen

person" from the label – in fact, the new label “implies” that

Dyer owns the patent. Nor would the public find any other

maker’s harp guitar labeled “Symphony” from here on out. I can

certainly see Dyer pushing for such a deal, and Knutsen might

have stopped worrying or caring after a while - especially if

they sweetened the licensing fee.

None of this quite explains the “patent” inclusion

on the Dyer label after 1912. In fact, Dyer never removed

the patent notice from their labels. It is still there on the

highest serial number we have a photographed label from. This

instrument is circa dated at 1922 in the old system, and in any

of my new timelines, still approaches 1920. How did they get

away with it? Well, as Tom explained, a patent holder was

allowed by law to leave a patent notice on a product even after

its patent had expired – and Knutsen himself did so, stating

“Knutsen’s Patents” on the post-1912 “New Hawaiian Family”

labels (which included a photo of an older harp guitar). Dyer

must have followed suit, although they were in a much shakier

gray area. A final frustrating fact is that Dyer included the

“Patented in U.S. & Canada” on the labels of the very first

to very last harp mandolins, even using them even on the

later (brand new) mandolas and mandocellos. Tom Noe has no

answer for this one, it seems to be a completely fraudulent

claim.

Bottom line: We have two very different options here, one of

which requires a paradigm shift. Neither is yet 100% provable.

Either the new 600 series Dyer label appeared in February, 1912

(as originally published by Bob Hartman), or it appeared in the

1906 to 1908 timeframe. I favor the earlier timeline, and,

after my latest serial number

statistical number crunching, have decided on mid-1908.

|

|

E) The “lower bass point” harp guitars built by both Knutsen

and the Larsons

|

|

A key question for both Knutsen and Dyer/Larson fans is

of course “who influenced who” – did Knutsen come up

with this distinctive design, or did the Larsons?

If we consider the full 1906-1908 timeframe for

the label / 600-series switchover, then things are

cloudy, as it would depend on how accurately we could

pinpoint both Knutsen’s first instrument of this type

and the exact date of Dyer’s new license / label /

600-series. However, again,

after number crunching, I found myself choosing mid-1908

for these events. |

|

|

|

|

Bottom line: I still have no proof, only a strong “gut

feeling” that Knutsen created this model, then the double-point

sometime in 1906, and that the Larsons briefly “copied” his

“lower bass point” design around the

middle of 1908.

|

|

F) The strange case of the “Style 3” |

|

In the previous version of this article (June,

2011), this was an extremely lengthy and troublesome

discussion of how in the world Dyer’s “Style 3”

appears to have occurred a few years after the Style

4 through 8. As it is something Bob Hartman and I

thought long and hard on, I have

archived it here.

However, since the discovery of Type 1 specimens

#120 and #125, I think we may be over-analyzing it.

|

|

|

|

|

The answer may be simply this: The specimen #125

(refer to my

Gregg’s Blogg article) finally

showed us that the label’s Style number did not include a

“U” or a “0” which we thought we were seeing on the identical

specimen 127. Instead, both turn out to be a Style 5.

Curiously, the plain appointments match the later Type 2’s

Style 4, not its Style 5 with top binding. But so what?

Obviously, Dyer/Larsons made a switch – a new ornamentation

designation system – when they brought out the Type 2.

My guess? Simply that when the first Type 1’s were

built for Dyer (beginning with the theoretical serial #101),

someone chose a simple numbering system that arbitrarily

assigned “5” as the lowest style number. Maybe it seemed like a

nice round number, who knows? Remember that they were just

getting started and probably hadn’t yet come up with the

specifics on how many “models” (of ornamentation) they might do.

As two of the four known Type 1 instruments match the later

Style 7 ornamentation, we know that there were at least two

“models/styles” (again, just using the original Knutsen Symphony

form).

A couple years, later, by the time the Type 2 was

designed, they had probably come up with the idea of their four

(then five) different “Styles.” For whatever reason, “4 was the

new 5” (to use a modern expression). Style 4 was now the

plain model, and there was nothing below it. And they were

off and running.

When they later decided to do the new “Seattle

Knutsen”-like, short scale instrument, they had a dilemma. This

was not a new “style” of ornamentation on the same

instrument; it was a whole new body style “model.” But,

for whatever reason (ability to just use the same labels?), they

simply assigned this new shape (which itself

occurred in a couple levels of ornamentation) its own “Style”

number. They could have picked anything – “3,””1,” even a word

like “Terz,” whatever. But they chose “3” which happened

to be adjacent to their existing lowest number.

Update, January, 2012:

The latest (sixth) Style 3 found (#610) is in the family of the

original owner, and family lore says it was purchased "about

1909." Accurate or not, that is

certainly close to my new proposed date of mid-1908!

Update, January, 2013:

A seventh Style 3 has long been hiding right under our noses,

owned by the late Bob Brozman. Curiously, it has a

somewhat later serial number: 673 (not a hard to read "613" but

definitely a "7" according to Bob. Without being able to see it,

I suggest that it is in fact "613".)

Bottom line: This is my current theory. As far as why they

chose “3,” who knows (or cares)? The dating, the timeline –

none of it matters for this discussion. We just have to accept

that we were fooled by an apparent “sequence” – Bob and I were

looking at “3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8” and stuck thinking

“consecutively,” wondering where Styles 1 and 2 were! Problem

solved…(?)

|

|

G) Duplicate serial numbers |

|

We now know that harp mandolins duplicated the same sequence as

harp guitars, but several years later. Just a couple of these

duplications are known. We also have long had many reports of

duplicate numbers; however, the majority of these are still

unverified (see bullet B above). However, we now know that

mistakes do happen and that there are Type 2 Dyer harp

guitars with the same serial number, with two

distinct legible handwritten labels. Three examples appear in my

serial list above (denoted with “(2)”).

Bottom line:

Please continue to photograph and submit your labels for

verification!

|

|