|

Scott Chinery wrote of this guitar, "I often think it

looks almost like a Gothic torture device." I have to agree!

And yet, there is a very thorough logic to Mr. Bohmann's ultimate

creation - in fact, nearly every feature was important enough that he

patented it.

Bohmann had earlier patents (including a strange hand rest for

bowlback mandolins in 1889), but the first one to concern us is # 1,128,217.

Applied for on Oct 28, 1911, it wasn't granted until 3-1/2 years later, on

Feb 9, 1915. The two key "improvements" it offered were a set of

sympathetic "strings" inside the body, and a bulging convex top

and back.

1,128,217b

1,128,217c

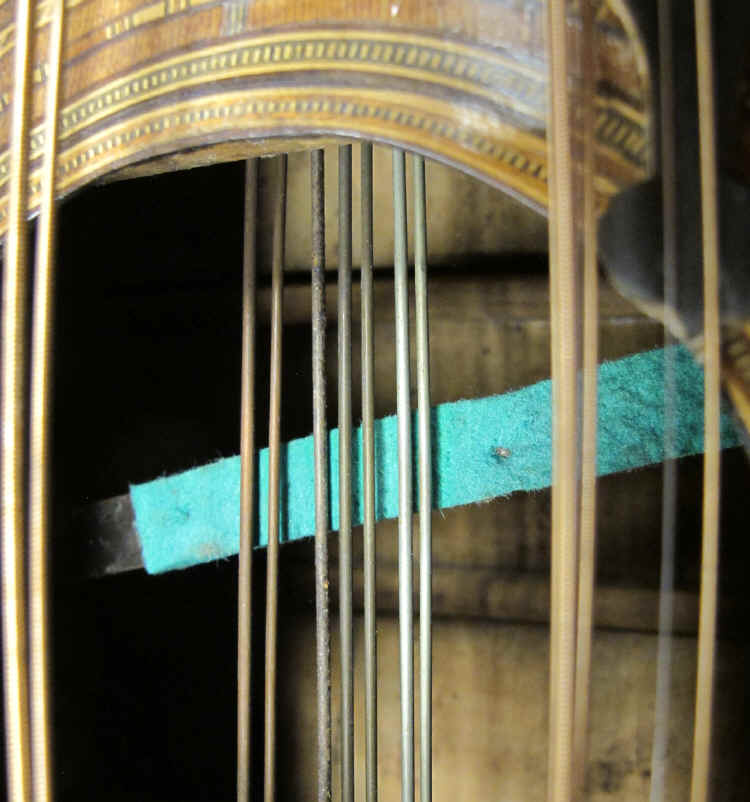

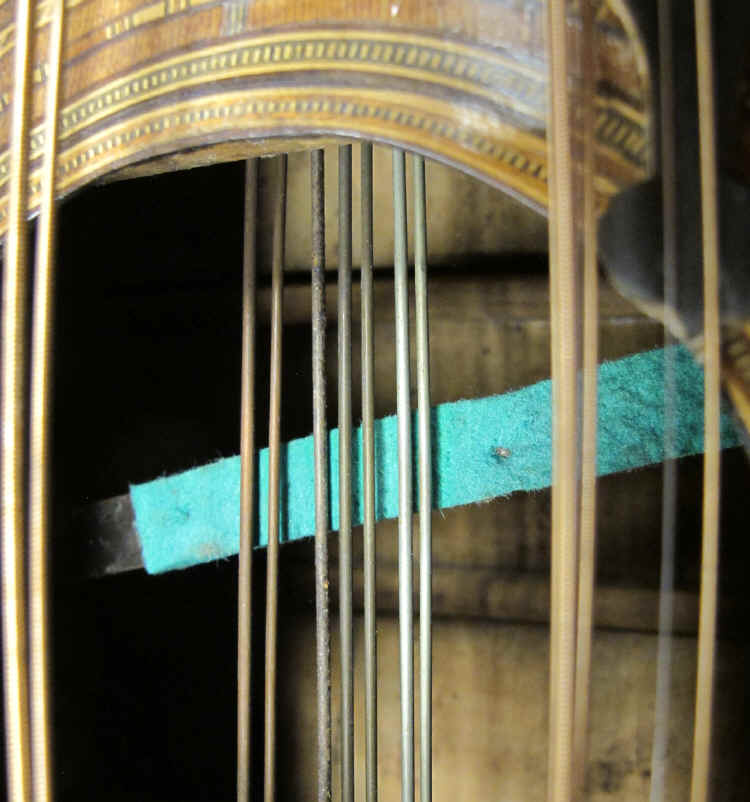

For the former, Bohmann attached

thin metal rods inside the instrument from the neck block to the end block. These

were then tuned, via wing nuts, to specific pitches, in order to vibrate in sympathy when played.

He

even figured out the best materials

to use - copper for G, brass for D, steel for C, and German silver for

F. Has anyone ever heard of this "musical metal matching"?! There was also a damper pad which could be locked into place or left

free by depressing a button next to the fingerboard. Four of these were

specified in the patent, but up to seven were used in the harp

guitars. You can count the seven rods through the soundhole of

Chinery's instrument below, and also see the damper pad, with the

activating button coming through the top to the right of the fingerboard

(with red felt border). Chinery said in his book that he heard little difference

between the damper On and Off positions - it seems like a lot of

work for such negligible effect!

I was able to finally test the metal tone rods for

myself in 2018. As Chinery said, there was little difference whether the

damper bar was engaged or not...that's because there was virtually zero

additional volume or vibration from this alleged magical reverb effect.

The rods were mostly stiff, but perhaps needed tightening and tuning to

the specific Bohmann pitches. I just can't see Bohmann spending so much

time on this unless at one time he did hear something!

The second part of the patent addressed the new construction: side walls

which were 1/4" thick, with the top and back assembled last,

bent under extreme tension.

Both concepts were to be applied to "A-shape" mandolins, guitars and "harps" (harp guitars).

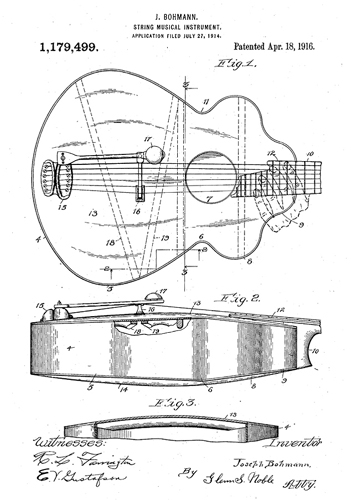

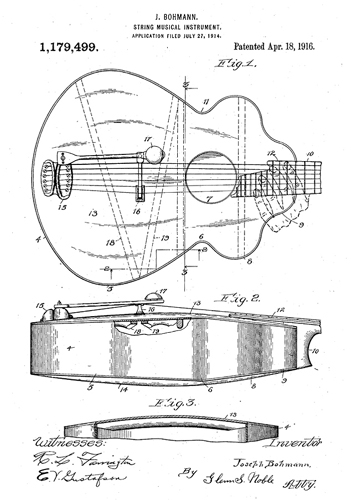

On

March 9 of 1914, Bohmann applied for a patent on his new hand rest,

tailpiece and

bridge combination. For reasons unknown, this was never granted, but the

elements were incorporated into the next patent he submitted just

four and a half months later on July 27.

This was granted two years later on April 18, 1916.

1,179,499b

1,179,499c

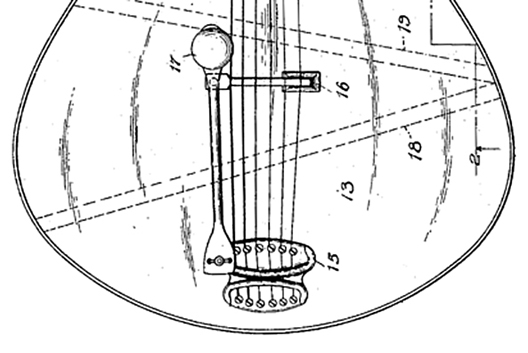

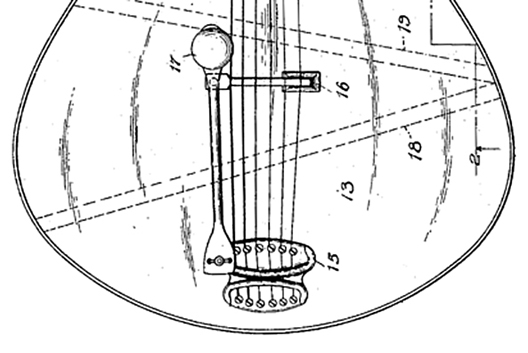

You

can see it in the patent and the other known harp guitars below that all

have the exact same device. Frank Ford mentioned how fragile

the one he inspected looked, doubting that it could have been used as a

hand rest - yet, amazingly, these wooden attachments are still intact on

all three harp guitars!

Bohmann

mentioned a "patent machine bridge" in his 1890s catalog.

We haven’t been able to locate a patent, so it was likely never

granted. We assume it was in reference to the configuration seen on his

c.1890-1900s harp guitars, especially the “Contra Bass” instruments

(below). Note that its "saddle" is incorporated into the

carving, with the neck replaced with bone.

However,

these

later ‘teens instruments feature something similar but much more

complex, as they are well separated with the tailpiece section doubled

up in an overly-elaborate single mirror-image carving. The top set of screws

in the double-tailpiece (here, two double-tailpieces, as it is a harp

guitar!) serve as

"guideposts," the strings then going underneath through holes

into the second tailpiece section. Another set of screws here are used to

attach the loop-end strings. Note that both the hand rest and the new

tailpiece/bridge array appear clearly in the patent.

Bohmann was quite clever

to include these features even if we was denied the chance to include

detailed descriptions. Instead, he is forced to write “…the tail

piece and bridge may be made in any desired form…” while sneaking in

“…I prefer to have them constructed in the manner shown in my

previous application for musical instrument, filed March 9, 1914…more

particularly in order to support the hand rest or guide, such as also

shown in said application.” In other words, he seemed to be covering

his bases, in the event that the earlier patent was denied (which it

was)!

The

patent illustration clearly shows the strings being guided under the

head of the screws on the bass side, going through holes in each

tailpiece and attaching (presumably via loop ends) to the second set of

screws.

Note

above that the instrument is now strung with ball-end strings (as

historical loop-end strings of these gauges are no longer made). The

main neck's string balls butt up against their top tailpiece lip, with

the anchor screws unused, while the sub-bass strings are jammed in

whichever way they can fit! (These are randomly gauged and strung and

not yet in the intended chromatic tuning.) On both string banks, the

strings are here resting in the slot of the screws, rather than tucked

underneath. Though

Chinery originally only strung the neck with six strings, this is

actually a 10-string, 6-course instrument, with the low four courses

doubled. It is now fully strung, in the manner of the well-known late

1890s Grunewald.

Other

than his mention of the separately-applied-for bridge design and hand

rest, this patent presented two new features. The first was the obvious

new body shape (the convex shape already established in his earlier

patent) – with a strange upper bout intended to make it easier to

access the higher frets (conveniently shown with the illustration of an

added invisible hand!).

The

second feature was a specific new layout of the top braces (shown in the

patent illustration).

Not mentioned in any patent (that we can find) are the

bizarre tuners in an even stranger headstock design that helps bring to

mind the "torture device."

Yes, those are Bohmann's

custom-fabricated pot metal tuning keys and hardware.

The carved "flattened scroll"

is extremely eye-catching, and then there are of course Bohmann's infamous

oversize and blunt fretboard inlays.

Note the raised lip of the sides over

the top. This violin-style embellishment is another striking late-period

Bohmann feature.

|