|

|

| The

36-String Harp Guitar

|

|

|

If you diligently read

Walsh’s Hobbies article

above, then you spotted the reference George Dudley’s wife Florence

made about his harp guitar: “…my

husband, George…played a 36-string harp guitar…”

Did your brain do a

double back flip? Mine also.

I logically assumed that it was either a typo, a mistake, or just

misconstrued word of mouth. And

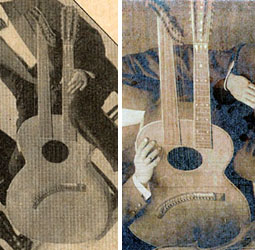

the quartet image in the poor Xerox of the Hobbies article didn’t tell

us a thing.

Luckily, Renee had a

better copy of that image, and a second, better photo of the same

instrument. Now we see that

the unusual instrument had twelve strings on the neck (6 doubled

courses). But how many

sub-basses? Well, we can

pretty easily count twelve, but look closely at the details.

Is it possible that there are actually two

rows of 12 zither pins for the chromatic sub-bass bank? |

Audley with early tenor banjo, and George with his 36-string harp guitar, circa 1910-1915

|

|

|

Yes! First

step is to look for octave strings, and they can be seen on the neck’s

low courses in the second image. They

are hard to resolve in the basses, but start counting and you’ll

definitely go beyond 12 – so they’re probably all there.

Next, compare these two images with the otherwise identical

instrument below that has just one

row of 12 sub-bass tuners, to get a better idea of the appearance of the

tuner layout. Dudley’s

remarkable instrument has a full 18 courses (12 bass + 6 neck), with

each doubled for a total of 36. Like

taking the 12-string guitar concept and applying it to the entire range

of a harp guitar! (Yes, that

is some serious string tension.)

Left: In a different quartet, George holds the tenor banjo, Audley holds a mandolin-banjo, and an unidentified performer holds George's harp guitar, c.1910-1915 |

|

|

I feared I wouldn’t be

able to identify the builder, but then I dug up these photos sent to me

by Mike Fleming, who photographed this instrument at Fred Oster's

Vintage Instruments for a Fall, 2008 Fretboard Journal

article. It

is an ultra-rare (only one, as far as I know) Holzapfel

& Beitel harp guitar, with – guess

what? – 12 strings on the neck. This

one has a full 12 bass courses also, but they are not doubled.

Every other particular seems to match: bass head, placement of

the necks, bridge, body and fretboard particulars (Dudley’s are bound

and have fancy markers), you name it.

I believe that George Dudley

owned – perhaps custom ordered – the

world’s first (and likely only) fully

double strung 36-string Holzapfel & Beitel harp guitar.

The time and place were right. Holzapfel & Beitel were in Baltimore in the 1900's, and Renee Ball tells us that “My grandfather George Dudley and his brother Audley owned a music shop - I believe on 42nd Street in New York. They sold instruments and sheet music, so that is probably how he bought the guitar.” Update

May, 2016: Corroboration! An undated letter from George

Dudley inquiring about the delivery of his harp guitar survives in the

Hopzapfel archives! (see Vintage Guitar, June, 2016) |

|

|

Unfortunately, there’s

no date in the extent specimen, and the two photos of Dudley’s

instrument are undated. Renee thought them to be before 1910, but that seemed too early, due to the presence of the tenor banjo in each photo.

I put the question – and possible identification of the banjos - to the Banjo Hangout

Forum, and the conclusion (mine as well) seems to be that the tenor is an Orpheum banjo and the mandolin-banjo is a Vega.

Neither model has specific provenance denoting the year of their introduction, but both could have been introduced as early as 1910.

They were certainly bought (and modified to include the sound hole in the skin head) by 1915, as Audley died

of tuberculosis in September, 1916; so we can reliably date both photos to between 1910 and 1915.

Ultimately, this only tells us that the harp guitar was built by that time, but could

of course have been built anytime before. How much earlier? In

following up with Mugwumps’ Michael Holmes on my recent “Birth

of the American 12-string” article, he shared this fascinating

tidbit:

"Music

Trades in 1900 (I didn't record the month, so perhaps the MT Annual) had an article about Holzapfel

& Beitel building 'large 24 stringed guitars and 12 stringed

mandolins for The Hollywood Mandolin Orchestra' of Baltimore. They were

probably 12 stringers, not 24."

In fact, it is no typo

– The Music Trade Review was almost certainly announcing the

very instrument shown above! The

term and concept of string “course” (paired or tripled strings

played as one “note”) remains confusing today, and was completely

ignored a hundred years ago. So

it was up to the reader’s imagination as to how Holzapfel & Beitel’s

“24-string guitar” might be configured.

And who at the time would have imagined such a cutting edge

instrument as a harp guitar with twelve sub-basses and doubled neck

strings? In fact, if Holmes’

date is correct (and you can usually take Michael’s notes to the

bank), then this is important

new information for both this article and

my 12-string article. The

firm of Holzapfel

& Beitel, a very obscure name today, is known mainly to a handful (but

growing number) of

12-string guitar historians and enthusiasts. As demonstrated in my

12-string article, the firm may very well have built America’s first 12-string

guitar (1901-1902). What I’m suggesting now is that their first

experiment could have actually have been a 12-strings-on-the-neck

harp guitar. Think about it. One

of the main ideas behind American harp guitars was bigger

+ more strings = more volume. Doubling

the neck strings would have been an easy way to get even more volume.

And so it would not surprise me in the least if the “birth of

America’s 12-string guitars” wasn’t jump-started with harp guitars

by Holzapfel & Beitel and other builders (many pre-1920 harp guitars with doubled

neck strings by different makers are known).

Dating provenance aside,

I can imagine either

the makers (Holzapfel & Beitel) or player/customer (George Dudley)

thinking: “Hey, if doubling the

neck strings is useful, why not double all the strings on an otherwise-18-string harp guitar?!”

And so they did.

Dudley’s instrument then could have been built as early as

1900, or at any time Holzapfel was in business (with, then without

Beitel), up until the date when the photos above were taken. I

suspect early, as Dudley’s 36-string so closely resembles the extant

24-string Holzapfel & Beitel harp guitar, and

that instrument matches the

description in the c.1900 Music Trade Review ad. As a side note, the 12-string mandolin (triple-course) that Audley was described as playing in the Walsh article was quite possibly the “12 stringed mandolin” also listed in the c.1900 Holzapfel ad.

|

|

Did George play the Holzapfel

on the

Ossman-Dudley recordings? That

would be extremely cool to hear, would it not?

Well, I find it impossible to tell, so perhaps readers/listeners

can help me out. The first

good news is that we can easily hear sub-basses being played on the

Trio's recordings. Why

is this so surprising? Because

until now, on every American 78rpm recording that includes a harp

guitarist that I’ve heard (usually Roy Butin or Horace Davis),

the sub-basses never seem to have been played.

(See my Harp Guitar Music

listings for some of those examples)

On this sample of Chicken

Chowder, you can easily hear George hitting a low B, A and later a D

(assuming the song pitched in E).

On all other songs with available sound samples, you'll always hear

at least 1 sub-bass, usually a B or a D, once even a chromatic Eb.

However, I'm not hearing doubled octave strings. In fact, on any Ossman-Dudley recordings,

does anyone hear octaves on any notes;

neck or subs? I can’t hear

them, though of course recording fidelity is problematic at best (I’ve

learned that the only real way to listen to

78’s is “live” on a great 78 player, preferably with the

right kind of acoustic “speaker.”). The closet I come to

imagining that I'm hearing a higher octave string with the low courses

on the neck is Dixie

Girl

.

|

|

It’s of course possible

that Dudley didn’t use the 36-string for the recordings, or got it

after they were done, (after 1907). There is also the possibility that

he removed some or all of the octave strings

during recording for one reason or another.

Walsh quotes the 1908

Victor record catalog in describing the trio’s sound: “…the

combination has made some extremely pleasing records.

The harp-guitar gives a support to the other instruments which is

decidedly effective." This

doesn’t tell us much either. Remember

that the other instruments in the group are Ossman’s bright banjo and

a triple-strung mandolin; there hardly seems room for more high strings

from Dudley’s 36 octave-strung courses!

Sadly, no one knows what became of George Dudley’s amazing Holzapfel 36-string harp guitar, or the brothers’ other instruments. But at least now, we know a bit more about the famous “unknown” Dudley brothers.

READERS: If

you have additional information about George Dudley, the Ossman-Dudley

Trio, or their instruments, please let me know!

|

|