|

|

|

|

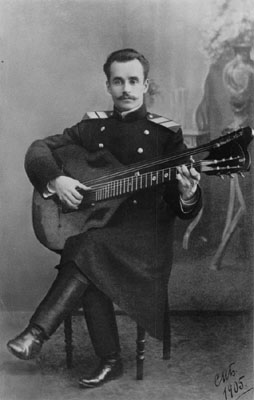

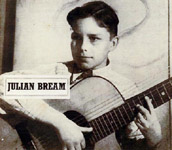

The wappen (shield)-shaped

instrument is in remarkable condition for one believed to have been

built in 1877 and eventually played for five decades by Perott.

In fact, it looks little different now from how it appears in

this 1905 photo of a dashing young Perott in Russia (courtesy again of the Gorelik family). We can

note a couple obvious features: It was originally built for Russian

guitar tuning, that is, 7 strings on the neck (tuned to an open G

chord), and 4 floating basses (typically C-E-F-A, to fill in the notes

around the neck’s low D & G [7th & 6th]

strings).

|

|

|

|

|

|

However, it is known that Perott preferred to concentrate solely on

standard 6-string neck tuning, and in every photo, including the 1905

image, we see that he strung his Russian-built harp guitar with only six strings on the neck. Curiously,

the current bridge only has pins for 10 strings, not 11, as it should

have had when built (to match the original 4 + 7 tuners and stringing).

Too bad Perott is covering up the bridge in the 1905 photo!

After some time, Peter Gorelik was able to inspect and

get decent photos of the underside of the bridge...and found that it

appears to be all original and with only ten string holes (below). I brainstormed this conundrum with kontragitarre aficionado

Benoît Meulle-Stef, and we came up with a couple possible

scenarios. The simplest answer would be that this was originally a

4 + 6, 10-string instrument, and that someone changed the neck before

Perott acquired it (he bought it a couple decades after it was

built). Perhaps the original broke and was replaced with something

convenient – in this case, a 7-string neck. A less convincing

scenario is one in which the maker intended on building a 10-string

instrument (I show one below, by the same maker), but ran out of

tuners. In other words, he didn't have the matching 3-plate for

the main neck's bass side. Seems unlikely? Well, consider

that the tuners used are still not correct. Ben noticed

that the 4-on-a-plate tuners used for the neck's low strings do not

follow standard Russian 7-string guitar practice. Every other

(typical) Russian 7-string utilizes a tuner set wherein the outer

rollers (top and bottom) of each side are in line, as

in this example. The half-set on Perott's harp guitar instead looks

like the same set used for the bass neck's 4 subs.

It seems we are left with a mystery, no matter

what! Ben also noted that the headstock originally had an ornament

(Cyrillic script?) affixed (in the 1905 photo). Today, we

can see small nail holes and an outline (roughly figure 8-shaped) from

where this was removed.

|

|

|

The "shield" body shape was not remotely unusual at this time

– neither in Leipzig nor its “sister city” St. Petersburg, where

this one was built – but might certainly have appeared strange to the

guitarists of London in the 1930s! This

is where Perott settled, and where he co-founded the PSG in 1929.

Proof of the unfamiliarity with such an instrument (or perhaps

any harp guitar, for that matter) in London is seen in that country’s

BMG (Banjo, Mandolin and Guitar) Magazine in the July, 1931 issue, where

Alexis Chess (A. Chesnakov, a co-founder of the PSG) answers curious

readers about Perott’s “peculiar-looking guitar.” NOTE

1

The 1931 article at left (kindly shared by Jan de

Kloe) finally identified the maker of Perott’s instrument as Paserbsky

(Frantz S.).

Jan at first told the owner that he thought it was around 120

years old (or c. 1890).

In the Stuart Button book, the guitar is identified

slightly differently: “This guitar was made in 1860 by Franz

Passierbski, a violin, guitar and balalaika maker of St. Petersburg. It

was originally obtained for Perott by his teacher, Vassilj Lebedev

(1867-1907). The instrument is unique and still survives today.” |

|

| I have no idea where Button got the information, but de

Kloe finally learned the true date, which he reveals in his book as 1877

(from personal correspondence between Perott and Gorelik). If

true, that makes it (as of this writing) 136 years old!

It was thus bought secondhand by Perott, with his teacher, Lebedev

(another Russian harp guitar player, in our encyclopedia here),

likely recommending or obtaining it for his student. |

|

|

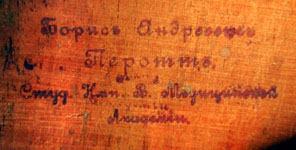

Jan further translated the existing inscription: “The

text on the guitar mentions that Perott is a stud(ent of) Nar. V.

Meditzinskiy Academy. ‘Nar’

stands for ‘narodny’ meaning ‘national’, ‘V’ stands for

Voyenno meaning Military. Perott was a student at the Military Medical

Institute where he studied to be a doctor (from 1902-1908). This academy

still exists today.”

About

a year ago, both Jan de Kloe and Oleg Timofeyev were able to

visit Stephen Gorelik and the Paserbsky. Jan (pictured) says that

Oleg (a true harp guitar player) "managed

very well, thanks probably to his exposure with comparable instruments."

|

|

|

|

Another interesting feature is what I call the “pinky rail.” Perott

was of the “older” classical guitar tradition that played with the

little finger resting on the soundboard (this was one of the criticisms

that would be brought against him by Bream supporters), so I immediately

realized that this was a handy finger rest installed to allow the hand

to easily move from playing near the fingerboard to near the bridge

(compare this to the shorter

finger rest that Coste installed

on his instruments).

I was originally of the opinion that this must have been added by

Perott after obtaining his secondhand instrument, as I’d never seen

another specimen or catalog image with this feature.

But then someone sent me an image of another Russian harp

guitar with the same exact pinky rail, and I’ve since seen others,

including a second Paserbsky in the collection of Ivan Bariev (at

right). Note on this one the "cut-out" of the finger

rail to match the soundhole. This original Paserbsky has 3

sub-basses and 6 strings on the neck (both 6 and 7 string necks were

simultaneously offered in St. Petersburg, and even in some German

catalogs). |

|

| It seems that this was apparently a somewhat more common

option than I had initially thought! (de Kloe’s book mentions “the

typical little bar…”; I’ve found this feature occurring on perhaps

ten percent of the several dozen Russian guitars I’ve now seen).

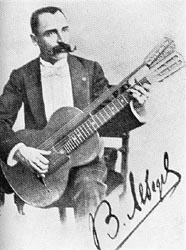

Interestingly, Perott’s teacher, Lebedev (who also played on

6-string necks) has the rail on each of his two known harp guitars

(at right). NOTE 2

|

|

|

|

|

I hinted at the start that this very instrument

instigated some controversy in the world of London’s guitar society

– and Button’s book goes into this in detail, one of the most

telling records we have concerning the periodic “war” between harp

guitars and “normal” guitars. Perott

has been described by more than one fellow guitarist (somewhat

disparagingly) as “old school.” Not

unpredictably then, he also advocated extra bass strings, although it is

not clear if he actually tried to push this agenda among his students or

Society members (I sense not). NOTE

3

No, it was actually Henry

Bream – Julian’s father and amateur plectrum guitarist – who

became defender of the harp guitar, though unfortunately in a rather

inexperienced and heavy-handed fashion.

Naïve and embarrassing, in fact, when one reads his many letters

to Wlifred Appleby, then the Society’s Journal editor - and vehement

despiser of extra strings (detailed in Button’s book).

After a chance encounter with this very harp guitar

at the home of Dr. Perott, Henry Bream fell in love with its tone and

possibilities. He first

divided the membership of the PSG by surprising the group with his

finished letterhead for the Journal, which prominently featured the

distinctive harp guitar in the center.

About half the group was seriously ticked off, as they didn’t

think it represented their forward-thinking serious “classical guitar”

efforts. |

|

|

| Then things got really ugly

when Henry bought his young prodigy son – horrors – a Maccaferri harp

guitar! Young Bream

actually used this for one of his early debuts, though didn’t use any

of the sub-basses. Appleby

– and many of the other members – thought it a “monstrosity.”

My take away from the narrative is that Perott didn’t seem to

care one way or the other if Julian played the Maccaferri – after all,

to him this was normal – and probably wouldn’t have pressed the matter.

But he still wasn’t fairing much better politically, as the

supporters of the prodigy Julian – which now included everyone –

debated over whether he should be resting his little finger on the

soundboard like his old-fashioned teacher Perott. |

|

|

|

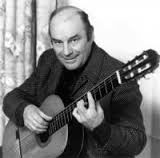

Though every single reference to Perott I find seems to prioritize his

celebrity as “Julian Bream’s first teacher,” Bream himself would

say many years later: “I had lessons with him after a little while,

for a year. He was an interesting man. He was quite old. He couldn’t

play anymore. But he was once in his youth quite a good guitarist. But

he played in the old Italian school, which is quite contrary to what the

modern Tarrega would be. And I found that the particular right hand

technique (i.e. resting the little finger – GM) wasn’t very useful for me.

Particularly for playing more Spanish and modern pieces. So after a

year, I discontinued and from then on, I was virtually learning on my

own.” |

|

|

Not to continue to dish on Perott, but I also seem

to find contrary views on the importance and place of the PSG among

those involved in the story of the classical guitar.

Button calls it a “society without direction, an obscure

movement, shrouded in mystery.” He

then quotes A. P. Sharpe, editor of the popular music BMG journal, who

wrote in his own magazine, “Many readers of BMG must have often

wondered just what the Philharmonic Society of Guitarists is and did.”

And Button, again: “Sharpe’s comment reflected the PSG’s

indolence, a society that promised so much yet accomplished so little…” Ouch. NOTE

4

Well, they tried.

And a few even tried to retain and include the “forgotten”

harp guitar as a legitimate classical instrument within their noble

society. Perott clearly wasn’t

shy or embarrassed about it.

I’m thrilled that his original Russian wappen-shaped harp

guitar made such waves in England and still survives after 136 years –

playable, yet! – as testament to Perott’s own strong-willed legacy.

Gorelik family: I hope you treasure and preserve your heirloom instrument.

And Mr. Bream:

ya could’a been a harp guitarist! |

From Boris Perott – A Life with

the Guitar

(Chanterelle, 2012)

|

|

|

NOTE 1: In

the same column, it’s interesting to see how Chesnakov describes

attending a London Maccaferri concert, listing the program, Maccaferri’s

steel thumbpick, and the guitar’s internal resonator…sadly, no

mention is made of extra strings, and it’s possible

– since this is mid-1931 – that Maccaferri was perhaps playing one

of his new Selmer prototype 6-strings.

NOTE

2: As for the left image of

Lebedev - it is

very rare to see a virtuoso guitar soloist of the Viennese or

Russian schools with 9 sub-basses; typically 2-4, occasionally 5,

would be it. Interestingly, the instrument on the right

apparently survives, owned by Matanya Ophee. On

the photos, one can just make out what appear to be repairs to the

soundboard that would presumably match where the little finger rail was

originally attached (Richard Brune or Gary Southwell could surely

confirm this).

NOTE

3: I remain mystified by

the fact that the BMG editor would publicly insult the PSG, even as

Perott was in the midst of his extensive decade-long series on “famous

guitarists” for the BMG (much of De Kloe’s valuable biography

consists of correcting Perott’s many errors in these articles). Button

makes his views clear, de Kloe is more kind.

NOTE

4: In his book, Jan de Kloe entirely avoids the subject of floating

strings, though we’re treated to a few (and only a few) from Perott,

himself. In his 64-article

BMG “Famous Guitarist” series, Perott manages to slip in here and

there references to players who used guitars with floating strings (harp

guitars). He wisely refrains

from soapboxing, but is not afraid to say things like: “Other great

virtuosi of the guitar, including…(names 11 total)…proved, without a

shadow of a doubt, that the additional strings facilitate technique and

improve the tone of the instrument considerably.”

And elsewhere, “Practically all Russian, and many German,

virtuosi used instruments strung with the additional strings.” And,

again: “But there is no doubt that additional strings augment the

volume of tone and richness of the chords.” Curiously, while

mentioning Schenck’s and then Mozzani’s hollow-arm harp guitars,

Perott first maintains that they were unsuccessful due to their size,

“which necessitated a new technique which players were loth (sic)

to acquire.” He continues

with the opinion that, with microphones available (apparently, Perott

was a fan of miking the classical guitar), there was no reason for

Mozzani’s experiments, implying that his old Paserbsky was better. But

in a subsequent article just three months later, he praises Maccaferri’s

similar guitars, “especially one with a double neck” – perhaps

specifically due to the resonators, or perhaps because Maccaferri was a

friend?

|

|