Featured Harp Guitar of the Month

Bohmann's

Contra Bass Harp Guitars:

Gargantuan and Groundbreaking!

by Gregg Miner, August, 2016

Updated June, 2019

|

|

|

Introduction More and more, vintage guitar and mandolin historians are beginning to recognize and appreciate the creativity and genius of Chicago luthier Joseph Bohmann (1848-1928). Bohmann even has an entry in the latest Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments, courtesy of his main biographer, Bruce Hammond. Though my main Bohmann page remains a bit out of date, I wanted to address one of his important instrument designs separately here: the "contra bass" size guitar and harp guitar. This seems to be pretty forward thinking for 1895! This then, is a new, detailed examination of the Bohmann catalog entries and the very few historical specimens known. There are now duplicate copies known of two distinct Bohmann catalogs, one likely from early 1896 and one from about 1899. We have scans of these thanks to (originally) Rich Myers (for the c.1899), and later, historian Bruce Hammond, Bohmann’s dedicated biographer (for both). |

|

In

order to understand Bohmann’s contra bass harp guitar

(or CBHG

for the duration of this article), we also need to

understand his Grand

Concert Contra Bass Guitar (GCCBG),

as they go hand and hand.

And it may be best to first investigate them in

the later c.1899 Bohmann catalog, then go

back and look at the c.1896 catalog, which has some

curious inconsistencies. |

|

Here

is one of the only fully intact original surviving GCCBG specimens known. As you can see, it’s huge!

(Its bridge is non-original.) Both

catalogs give the body dimensions (for the CBHG)

as 23” in length, 19” in width and 6” in depth.

In the c.1899 catalog (immediately below), the harp guitar was offered in a 12-string or 18-string version – meaning, with either six or twelve sub-bass strings. One could ask for any one of Bohmann’s “regular guitar styles from No. 1 to 14, inclusive.” |

|

Having studied the c.1899 entry above, let’s examine the other (below). Approximately four years earlier, Bohmann’s c.1896 catalog lists what is certainly the very same two instruments, though appears to be rife with errors – all of them having then been cleared up in the c.1899 catalog above. See

how the 6-string GCCBG is described as “with double

neck,” confounding this curious error further by the offer

of “Add $8.00 for ea. extra string wanted.”

Clearly, it was the CBHG on the facing page

that had two necks (as it states). And

the harp guitar version had its own $8 “additional

string” option, where it made sense.

This must have been something equivalent to a simple

“copy/paste” error of the typesetters. On

the CBHG page, we find an even more incredible claim: “This

guitar is made in 18 to 32 strings.”(!)

Impossible?

Well, no – around 1900 Hopzapfel would build George

Dudley his incredible fully-double-course 36-string harp

guitar. Was Bohmann involved in such outrageousness earlier?

Or was this another typesetter’s mistake (mis-read)?

Thirty-two is certainly an odd number, whatever

combination of neck and subs we envision, so I believe it is

an error. And of course, in the next catalog, he writes “12

or 18-string,” which makes more sense.

He also fixes the GCCBG information and other errors

like correcting to “inclusive,” rather than “1 to 14,

exclusive.” |

|

The

c.1896 catalog does not picture either instrument

(perhaps they were just too new?), but features on the

following page the striking photo of Calamara. Bohmann proclaims that “This cut represents The

Contra Bass Harp Guitar and the eminent guitar virtuoso

Sig. Emilio Calamara, professor of the first Contra Bass

Harp Guitar, made in America by the world’s Greatest

Musical Instrument Manufacturer Joseph Bohmann.” (For those new to the world of Joseph Bohmann, yes, he quickly proclaimed himself as “the World’s Greatest Musical Instrument Manufacturer,” though not entirely unmerited, as he won exhibition prizes year after year – seven, in fact, from 1889 to 1900.) |

| The

same photo of Calamara and his instrument was used again

in the second catalog and (at left) on sheet music from

1897 For more on Calamara (and his wife), see Emilio and Emily Calamara: A Tale of Two Musicians |

|

This then, would seem to be Bohmann’s CBHG “prototype.” It has twelve sub-basses and one-of-a-kind headstocks. It looks narrower in the upper bout and waist, so may not have achieved it’s maximum size until the c.1896 catalog. Bruce and I conjecture that this was quite possibly the guitar alluded to in Calamara’s personal letter to Bohmann dated December 30, 1892 (at right), even though no details of the guitar were given. Calamara had been playing what looks like an Italian harp guitar of unknown make, seen in a single photograph in the Valisi Orchestra for some time prior to switching to the Bohmann (below). As

wonderful as the Calamara image is, the key image in the

c.1899 catalog is of Bohmann himself, complete with his

own CBHG (or two): |

|

The

text confirms that the

twelve sub-bass

strings were tuned chromatically; at what pitch, we

don’t know, but Eb down to E is the most logical

guess. I’m

still trying to hear in my head the musical effects

described by “As a solo instrument, beautiful sweeping

arpeggios can be made on the chromatic strings, and also

runs in thirds and fifths not possible otherwise.” This

CBHG, built by Bohmann

before 1896, has

six strings on the neck and twelve subs on a neck of the

same length (though the bridge lengthens the

increasingly lower strings some). Interestingly, it looks like Bohmann may be

color-coding his basses, much like Gibson soon would.

We assume his instrument has his dramatic and

groundbreaking sunburst back and sides – judging from

the instrument sitting sideways to the camera, which

looks like another CBHG. Surprisingly, neither catalog mentions his

dramatic and incredibly groundbreaking sunburst finish

option. |

|

This 1898 sheet music (courtesy of Barry Trott) depicts an all-female ensemble from Portland, Oregon. The accompanist is no delicate flower – she is handling a full size Bohmann contra bass harp guitar! Hers also has twelve subs, with headstocks different than either Calamara’s or Bohmann’s. Bohmann made other normal sized harp guitars similar in appearance to the CBHG and with that same bridge, so it’s a little tricky to positively identify these without knowing the size of the performers. But in this case, the high position of the bridge reveals the much larger soundboard area below it.

There are many more historical photos of Bohmann harp guitar players on my original main page, but none include instruments as large as the Contra Bass Harp Guitar. |

|

|

||

|

Why ten strings? Note that the four lowest courses are doubled in octaves as in the standard 12-string guitar, while the top two courses are single. As outlined in my article “The Birth of the American 12-string Guitar,” this configuration was a “new invention” of 1896 that quickly evolved into the full-blown American 12-string guitar around 1900. Odds are good that Bohmann may have been aware of this evolutionary “missing link” – the Grunewald-built 10-string. If Bohmann subscribed to the Music Trade Review, he would have had to have known about it. Or perhaps Linscott had learned of this intriguing new stringing option and requested it. |

||

| Update: May, 2018: Linscott found! | |

|

© Wisconsin Historical Society. Image # WHi-17307. Used by Permission. My colleague Paul

Ruppa located the photograph above on the site of the Wisconsin Historical

Society. The group is Clarence Fehling's

Old Timer's Orchestra, rehearsing at Fehling's home in

Madison, Wisconsin. This is clearly far from New

York, where his family thought he may have worked

– but perhaps he ended up here later in life. No names

are provided for any of the players, but I assume that

this is indeed Linscott with his harp guitar as the instrument stayed in

the family and is in the same configuration as when I

acquired it. I overlaid a current photo over his

just to make sure it was mine, but there was really no

need. There is his homemade metal bridge support

strap, just as I found it (which Kerry Char successfully

removed during restoration). The somewhat crude and

overkill custom inlays are all present and accounted for

(he’s missing one – a few others would go missing by

the time I got it several decades later.). The

photograph was taken on May 22, 1933 |

|

| Restoration:

Happily, when restorer Kerry Char removed the added tailpiece, we discovered the top was perfectly intact and visually presentable. Of course a huge swath of the soundboard has been worn to “washboard condition,” as is the fingerboard – Linscott clearly played the hell out of this thing!

|

When Kerry removed the back, he found an even bigger surprise: Bohmann’s incredible lattice bracing. At left is as found – all original, with an added portion to the brace below the soundhole (above). Note the narrow bits of bridge plate portions with screws poking through, part of Bohmann’s unique pinless bridge (see below). Below, Kerry has replaced the top three braces and strengthened that compromised area with an extra layer of spruce. Note also the full width heel block! |

|

|

|

| Somehow this elaborate mess keeps the instrument stable without deadening the sound. This sucker is a monster. Musicians speak nebulously of “depth of tone” – but here is true tonal depth! | |

| At left is Bohmann’s humongous

“label” (really more like an “internal

advertisement”!) which seems to date this

instrument to 1900 or shortly after. For some reason, he cut off the upper right

corner (nothing was printed there). He then pasted over this large label a cutting

from his trade card, showing his seven exhibition awards

from 1889 to 1900). At the bottom he also pastes in his then-current

address, which he was leasing years earlier.

The problem with dating Bohmann's instruments is that we have ample evidence of him warehousing unfinished instruments (you'll see one below) – for years or even decades. So features that appear to be earlier can be seen with features or clues that seem to point to much later (specifically, the patented internal tone rods). So he might well have started this instrument in the mid or later 1890's but finished it for Linscott much later. |

|

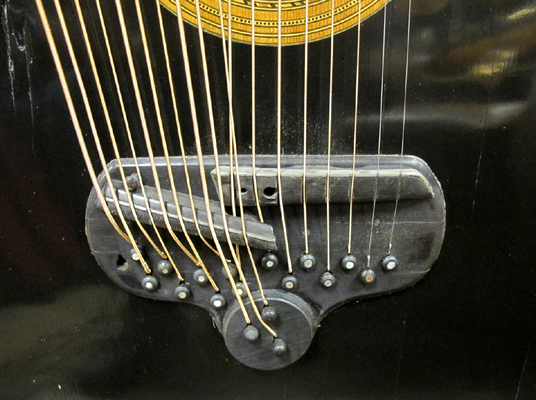

| Bohmann utilized nearly the entire gamut of sub-bass stringing options on his harp guitars, anywhere from 3 to 12. This instrument was tuned chromatically (probably Eb down to low E), and likely strung with then-common ball end silk & steel strings. I just love Bohmann’s bridges. I’m not sure if I’ve strung the neck strings exactly as planned (Bohmann chose to double them up on his standard 6-string layout), but it works! | |

|

When Bohmann’s shop was unearthed sometime in the 1960’s, two more, somewhat different, CBHGs were found among the many treasures. The first appeared almost identical to Bohmann’s own lap-held instrument, but was incomplete. It had both necks in place on a body complete with sunburst finish and six internal tone rods installed. It was just missing the bridge and tuners. Here it is as

found, photographed by Bruce Hammond at Ax-In-Hand,

whose original owner Larry Henricksen bought up the

Bohmann time-capsule inventory a few decades ago.

I’ve yet to learn of any production guitars

with a sunburst finish earlier than Bohmann’s 1890’s

instruments – surely this is a topic ripe for

investigation! |

|

Interestingly, Bruce Hammond has observed that for early "Era 1" (pre-1910) Bohmann instruments, the striking sunburst finish appeared only on birdseye maple instruments, not flame maple, which received a uniform natural finish. On Era 2 (post-1910) instruments, Bohmann applied it to flame maple as well.

This Ax-In-Hand CBHG eventually made its way to Mike Anderson of Elkhart, Indiana, who had repairman Ron Koivisto (at right) complete it in 2013. This short article tells how “the restoration project sent Koivisto on a series of internet investigations to deduce the right size and shape for the bridge, how to affix it, what gauge of strings to use, how to tune it and a dozen other puzzles.” I was never contacted by Ron, but I hope my site and articles came in handy (perhaps not...the article refers to it as a “guitar harp”). |

|

Specimen #3 The

other CBHG found in the Bohmann shop discovery was a

strange chimera of a thing.

The size and shape appear the same as the

previous instruments, though the back is even more

heavily domed – which coincides with a later date (the

instrument is stamped #1910). It has flame maple back and sides and a natural

finish. Though

they were missing when discovered, it originally had the

same six internal tone rods. Bridge pins now plug the holes in the butt of the

body.

The bridge is pure Bohmann from this later period, but appears to have replaced an earlier bridge, likely two separate bridges similar to the harp guitars mentioned above. Similarly bizarre are the 8 single strings on the neck, the lower two which are actually over "false frets" and are actually meant to pair with the ten sub-basses for a full chromatic octave! |

||

|

|

|

|

Bruce

and I have no idea quite what to make of this one! Here

are the two above specimens (#2 and #3) taken side by side by Bruce

at Ax-In-Hand. They

both have flat spruce tops and similar maple bodies – one

birdseye, one flame – with two

different finishes. |

||

|

One

question we have is whether Bohmann used maple ply

on his maple-bodied instruments, because he always used

ply on his rosewood instruments (Brazilian

rosewood/maple/Brazilian rosewood). I don’t know if that was meant for tone,

durability or for easier steaming over his giant heated

cast iron molds. His

rosewood instruments invariably show the fine cracking

and “feathering” of the outer Brazilian rosewood

layer. The

unfinished Brazilian rosewood inside weathers better.

Mine had significant back separation near a lower

bout so we were able to see the thin maple layer

sandwiched therein (regrettably, we didn’t measure or

photograph it). |

||

| The nice part is that I was able to see it at all. Up close and personal, this is just an incredibly wonderful and wacky instrument! I was also able to photograph additional details. | |

|

|

The "1161 Madison, Chicago" address stamped into the back of the body is surely a clue...

|

Note that these are

just a small sampling of Bohmann’s incredible harp

guitars. |

|

Or back to: Harp Guitar of the Month: Archives

|

|

If you enjoyed this article, or found it

useful for research, please consider making a donation to The

Harp Guitar Foundation, |

|

|

|

All Site Contents Copyright © Gregg Miner,2004-2019. All Rights Reserved. Copyright and Fair Use of material and use of images: See Copyright and Fair Use policy. |