The sixth in my special series celebrating women harp guitarists for 2021’s Women’s History Month features guest author Bruce Hammond, expert, and collaborator on all things related to the world-famous yet still enigmatic Chicago harp guitar maker Joseph Bohmann. This is a single-artist profile on a remarkable young woman who went from harp guitar-playing musician to American painter abroad. Enjoy! Gregg Miner

Grace Ravlin: Transcendent Artist

By Bruce Hammond

Thank you, readers – especially ladies, for having me. This is dedicated to my dear departed mother, Aline Bartosh Hammond.

Mom sang boldly, with the best soprano voice in the choir. Once warmed up, she rarely if ever missed a note. Evenings, she might burst into tunes from The Sound of Music. At times, the thought “Julie Andrews – my eternal persecutor!” came to mind. There was something about it I found enjoyable, though. Even today, certain female voices enthrall me. While Mother was certainly accomplished in music, other women achieve far more in the art world. Today’s featured woman expressed gifts in both worlds: music and art.

My Bohmann research began in 2005 after I bought three of his fretted instruments. Two years later, I took a short Illinois vacation. As I poked around a densely cluttered barn, I saw many Bohmann factory artifacts – but his letters really caught my eye! Once home, I bought the small letter cache. From thinking, “I own them,” my thoughts morphed to, “they own me.” Today, I remain that barn’s captive, haunted by those letters. Since then, my small archive has unlocked doors to strange new worlds, and I am now – by accident – a historian.

Our feature photo shows a women’s mandolin group. This rare, beautiful cabinet card came to me in October 2013. Just look at them! Every bit the dressmaker’s dream, these ladies are a period wardrobe designer’s delight. Four mandolins, one mandola (or octave mandola, as per Paul Ruppa), two vocalists, a typical guitar, and a harp guitar with 8 sub-bass strings. The lady in the front row, far right, holds a harp guitar built by Joseph Bohmann – it seems obvious she played it. Who was this fetching, young lass? If she chose to play harp guitar, she was bold.

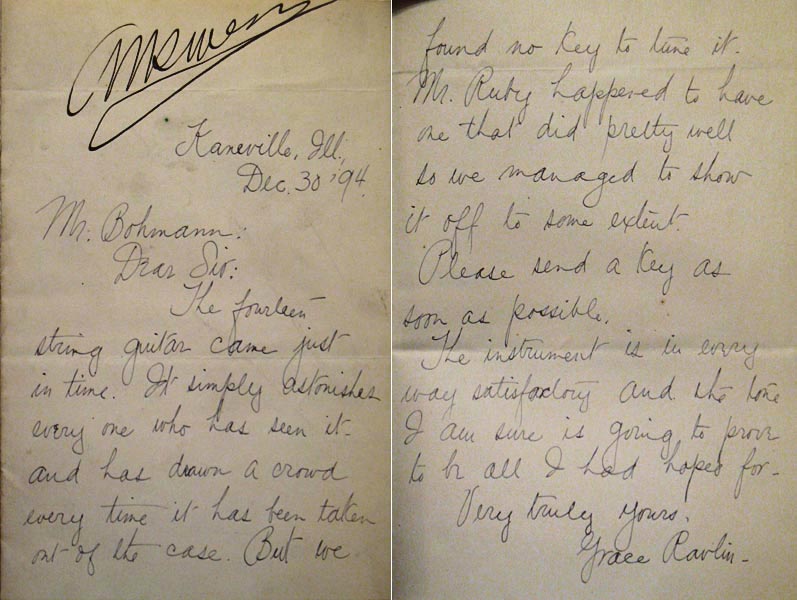

Gregg knew my archive held two letters to Bohmann from Kaneville, Illinois in the artful hand of one Grace Ravlin. The first letter, dated Dec. 30, 1894, thanked Mr. Bohmann for the 14-string guitar. Grace was enthusiastic. Perhaps she was still filled with holiday spirit. Was this harp guitar her Christmas gift? Possibly.

The ensemble photo struck Gregg and me like a bolt out of the blue. Recalling the above letter, we thought, “This must be Grace in the photo!” To say we were thunderstruck is an understatement.

Shockingly, Gregg had then recently acquired a Bohmann harp guitar identical to the one pictured (above). It is the only extant instrument identical to the “Ravlin model” 14-string Bohmann harp guitar in existence – and quite possibly, belonged to Grace Ravlin.

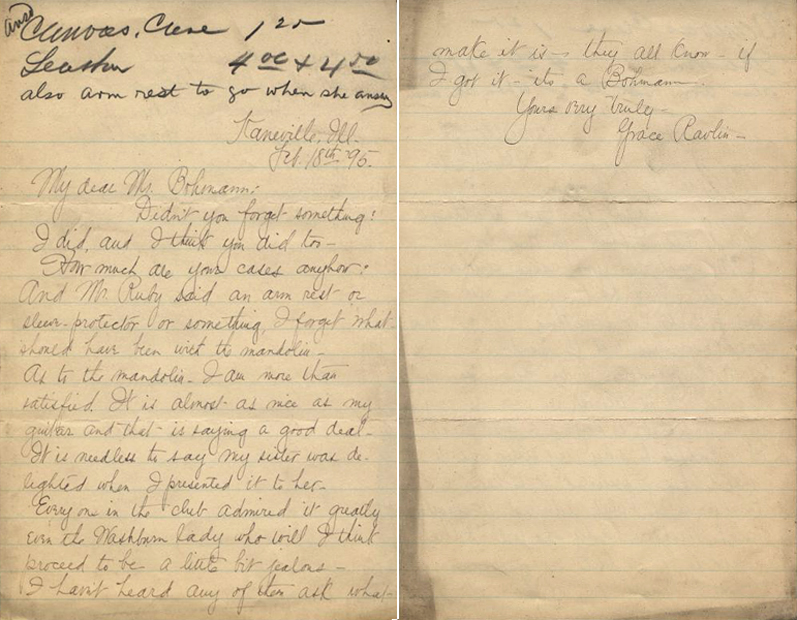

Shortly after the photo arrived, I contacted Grace Ravlin’s great-niece, Alta Ann Parkins Morris. Mrs. Morris confirmed that the harp guitarist was indeed Grace Ravlin. “Grace was always in the front,” she said. She also revealed that Grace’s sister, Alta, was in the rear row, on the far right. Grace’s second letter to Bohmann (Feb. 18, 1895) thanked him for the mandolin, saying it was as good as her guitar, and that her sister loved it. In a playful tone, she asked Bohmann, “Did you forget something? I did.” (the prices for mandolin cases…)

Late in life, Grace sent her niece Alta Turner (her sister’s namesake) most of her letters, datebooks, and scrapbooks. In turn, Alta Turner’s daughter Alta Ann Parkins Morris inherited the documents. She hosted a website as early as 2011, appealing for readers’ help in uncovering more of Grace’s letters and work. Grace’s two letters to Bohmann from my archive were the first letters Mrs. Morris saw outside her own collection – but more are out there, somewhere.

Grace was born in Kaneville township, Illinois in 1873, dying in 1956. (Kaneville is a small township about 53 miles west of Chicago.) She was the youngest of five children in her family. We are told Grace “followed the path of her four older siblings, doing chores on the farm, attending local schools, joining family members and friends in community musicales.” Obviously, she enjoyed making music. What music did people perform in Kaneville township? Did Grace sing? I’ll bet she did.

The current Grace Ravlin website bio states, “Grace had entered the school with dreams of a life centered on music; after all, hers was a musical family…. She herself played the piano and guitar, and composed songs and marches. Four years later, she emerged determined to have a career as a fine artist, but in painting, not music, an ambition no one in the family had ever pursued. . .” This indicates a hunger for music Grace sought to fill, for some years. As her art talent blossomed, it displaced her interest in a music career. We would like to learn more about the music she appreciated and performed.

Some clues to her musical culture come from her ancestry. Grace’s “paternal grandfather, Thomas, was a Baptist minister and an early settler and major land-owner there. Her father, Neeham Nicaner, was the village’s… postmaster…”

We assume Grace’s family were Baptist church members. Her online bios have never detailed her or her siblings performing church music. Most American Baptist churches did not make special celebrations out of either Christmas or Easter prior to 1900. Kaneville Baptist church(es) held no Christmas or Easter plays or pageants we know of. This begs more inquiries as to whether the “community musicales” mentioned earlier were church events, or church-sponsored in some way. Perhaps 19th century Illinois Baptist historians can help with this matter. Evidence indicates Grace went far beyond the Baptist hymnal.

When she was sixteen (in 1889) … Grace’s father sent her to public high school in Chicago for further academic studies. There, she took extracurricular classes at the noted Art Institute of Chicago. According to Grace’s great-niece Alta, Grace graduated from high school in1893. From 1891-1904, while still in high school, Grace studied at the Art Institute of Chicago with John Vanderpoel. Then she spent two years at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts with William Merritt Chase, a major proponent of American Impressionism.

Courtesy of Mrs. Morris, we can say Grace Ravlin was twenty-two when her group photo was taken. She wrote, “That was taken two years after she graduated from Chicago’s South Division High School. In the year of the photo, she was still thinking that she would become a musician and by 1898 and 1899 she had published a few compositions as sheet music for piano, and one for tenor (voice), a patriotic song at the time of the Spanish-American war! There were probably only four of these publications.” Playing music and the guitar were more than passing fancies for Grace. Current data indicate her playing spanned five or six years, possibly more. Did Grace compose any harp guitar music? We don’t know.

Grace’s intense drive, coupled with continual positive reinforcement from her art instructors inspired her to travel to Paris in 1906. Her transatlantic voyage astonished her family – especially after Grace wrote her sister in the fall to say she would be continuing her formal training in painting, remaining in Paris for Christmas. Occasionally, a family member wrote urging her to give up and return home. Grace replied, “Good gracious… this is no time to go home. This is my time to dig in. I’d really like to amount to something if I could.” Grace continued to dig in, tenaciously pursuing her art career.

For the next eight years, Grace painted in Tunisia, Morocco, Venice, the Italian Riviera, Provence, Brittany, More, and Geours in France, and Holland. Political instability forced her back home as WWI neared. Grace, a woman traveler, could not safely venture out alone at night. In fact, Grace also encountered obstacles in daylight. But Grace always persevered, creating an amazing number of paintings. Many more await discovery and a large format southwest painting would prove quite rewarding.

Did Grace have talent? During her European travels, she won awards; five of her works were purchased for a museum collection. In her 1906 letter from Paris, she wrote, “… I’ve been very nicely-recognized by all the artists in sight. And two or three of these men will be more help to me in Paris than a hundred ordinary people.” She won an award medal at the 1915 Pan Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. In 1916 and 1917 Grace traveled to New Mexico. Her southwest paintings became Grace’s best-known works. Many awards confirm her high talent level.

Grace’s expressive letters evinced a you-are-there quality. Often, she penned vivid descriptions of her brightly colored scenes. Her vibrant, lifelike letters inspired her niece, Alta Turner, to seriously study weaving in 1950. Mrs. Turner then wrote a book, traveled to many places Grace had written letters about and delivered numerous lectures to weavers’ conventions around America.

Returning to Europe in 1919, Grace worked for the Red Cross, painting in her spare time. She volunteered for Red Cross work anytime America was at war, reflecting the patriotic values of her home community. In 1921 she returned to America, “where she lived, traveled and continued to paint for about 20 more years.” In 1982, Alta Turner’s daughter, Alta Ann Parkins Morris, became keeper of Grace Ravlin’s records. In 2007, Eva Moore began collaborating on Grace’s biography with Mrs. Morris and their book was published in June 2020.

What was Grace thinking as she pursued her career? Newspaper reviews assure us that Grace had a palette that was all her own. If readers are interested, Grace’s own letters reveal her personality and career far better than we can in this limited space. If your curiosity is piqued, get her biography.

Grace Ravlin’s conserved documents offer a sterling example – and object lesson – to anyone wanting to preserve history. Even having all that, answers to many questions elude us. Many more of Grace’s paintings and letters await discovery. So, no! – don’t throw away those old letters and documents in your attic or basement! Find someone interested in them. Discovering new Carmen Symphony Club’s performance dates and programs is a good place to start research. Maybe someone will find more of her compositions.

If you or someone in your family want to preserve history, then be a facilitator. Get them or yourself training; start writing. Do something – even if only making a donation to a historical group or organization. Grace Ravlin’s family offers such a great example – I wish more people would follow it.

News Break! As of Saturday, March 13, 2021, we can now name our mandolin group and every member in our featured photo. From 1890’s Kaneville, Illinois, we proudly present:

The Carmen Symphony Club

Back row: Addie Lovell Merrill, Carrie Adams, Alta Ravlin Humiston (Grace’s sister).

Center row: Lettie Lovell Phelps, Hattie Lewis, Julia Fink, Myrtle Goddwin Spencer.

Front row: Belle Humiston, Grace Ravlin. (Data courtesy of Kaneville Township Historical Society)

Author’s note: As usual, answers to one question spawn more questions. Grace’s bio has a photo of Grace holding her harp guitar, and a man named George Shephardson sits at her feet. Was this man her music instructor? A mandolin duo partner? If not, who was he? Readers, any help?

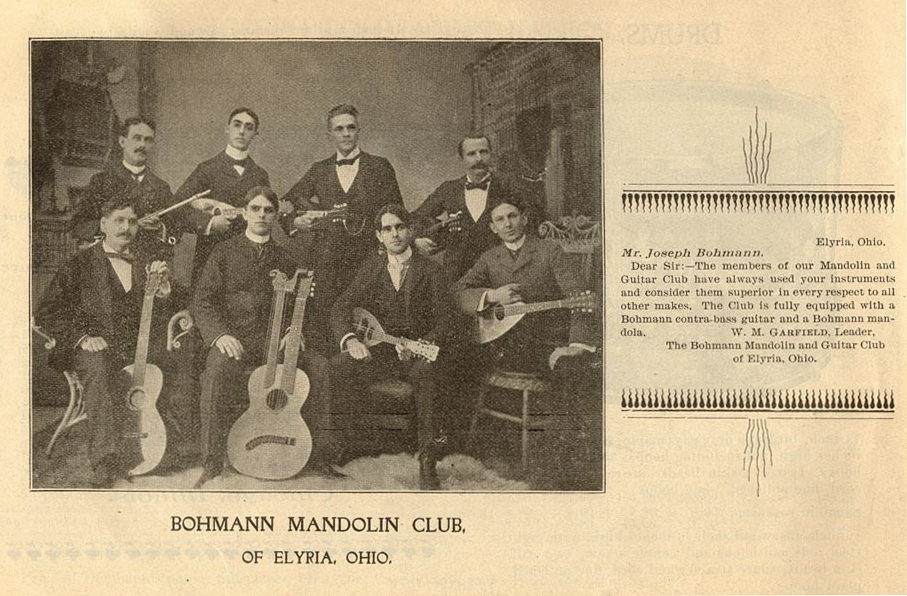

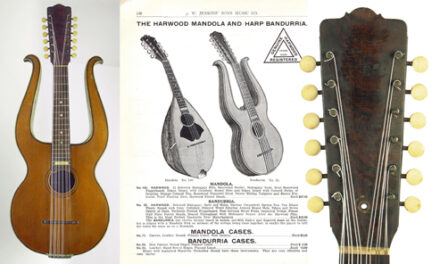

Appendix: Bohmann’s 14-string harp guitars with 8 sub-bass strings

Bohmann’s rare harp guitars show such a diversity that tracing their evolution and build dates is rife with problems. Every few years, a new variation emerges, and the majority of these newly-discovered models do not appear in his catalogs. A variant of the basic Ravlin model appears in a Bohmann catalog (1899) group photo but is not listed in his catalog. It is essentially identical to hers except for having the two “necks” centered on the body.

As we know, Grace’s instrument was built sometime before December 1894. But while we know about when Grace received her instrument, we cannot know how long it had been completed in Bohmann’s shop, waiting for a customer. Bohmann had a continual habit of warehousing large quantities of instruments until his 1928 death. Indeed, in the 1960s, factory visitors said they counted between three and five thousand instruments in various stages of completion. The factory had sat mothballed for forty-odd years in Chicago’s inner loop area – a story of another time, for another time.

A second 14-string Bohmann guitar survives; it has a larger body and a straight bridge, but possibly had a similar carved bass head before it was broken off and lost.

Above: the four known images of Bohmann 14-string harp guitars. Grace’s and Gregg’s are identical.

The Bohmann harp guitar that fell into Gregg’s hands possessed remarkable sonic qualities. “This one is indeed a cannon – loud and full-bodied…. the “secret sauce” is the inherent sympathetic vibration. You’ve all heard about it – harp guitars have all this extra resonance from the open bass strings vibrating in sympathy. In truth, some have a mild amount, and some have a nice healthy dose (like the Dyers), and this… you just cannot believe it. Like playing a small-bodied Martin steel-string through a Fender Twin Reverb.” It is easy to see why Grace Ravlin was happy with her Bohmann harp guitar.

Again, on his harpguitarmusic.com listing, Gregg writes: “I don’t know how Bohmann did it. The top is fairly thick (roughly an eighth inch), with light X-bracing (triple-X, with offshoots below and to either side of the main X), only 14-1/2″ wide, with laminated rosewood back and sides…” Let us consider the weight and construction of Bohmann guitars.

Anyone who ever played a pre-war Martin 0 or 00 guitar knew they were holding an exceedingly light instrument that produces an incredible amount of sound per pound. Chances are, if you like that type of instrument, you would not much care for something like a Lowden- quite a heavy guitar, which puts out in surprising volume and a pleasing tone, and has its share of fans. So, you can see that a heavy guitar, and/or a thick topped one, does not necessarily mean it won’t be loud. Some say Bohmann built his guitars like tanks, and his guitars are sturdy, indeed. His laminated sides and back greatly increased his instruments’ strength and rigidity.

We can peruse Bohmann’s description of his laminated guitars in both his 1896 and 1899 catalogs. (We used to date his first catalog as 1895, before discovering that the awards from the 1895 Atlanta Exposition were not granted until 1896.)

In 1896, Bohmann wrote, “Every purchaser of a Bohmann guitar is protected by a guarantee from the manufacturer that the instrument is absolutely perfect in every respect, will improve in tone with usage, and will not crack, owing to construction of sides and back, which are made of three veneers, the centre thickness forming across the peculiar grain, thereby precluding any possibility of splitting under ordinary circumstances, especially where extreme atmospheric changes frequently occur…. Only the highest grade of very old and thoroughly seasoned wood is employed in the manufacture of Bohmann instruments. Rosewood and the finest birdseye maple and curly maple are used in the manufacturing of the Famous Bohmann Guitars.”

“The Famous Joseph Bohmann Guitar” title page’s only change in 1899 was, “… forming a cross of the grain…”. Famous, huh? No modesty there. In current times, Bohmann’s style is considered bombastic, but examining competitor’s advertisements, most of them seem outrageous as well. So Bohmann was a child of his age, in marketing terms.

Imagine if a modern luthier recreated this Grace Ravlin harp guitar with improvements… With sub-bass and main neck strings located on the same plane? (Her sub-basses rise substantially higher at the nut.) With quality tuners? Very thin finish? Sunburst? Internal metal bars for more resonance? Now we’re talking!!

Any readers or luthiers have a honey-do list for this project?

_________________________________________________

(Gregg here: And now I really regret selling that harp guitar!)

Next: Our final historical European players!

Sources

- Bruce Hammond collection

- Illinois Women Artists, Part 32: Grace Ravlin (1873-1956): A Wartime Interlude – An Artist Returns Home. Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Nov/Dec 2017. (https://www.historyillinois.org/publications/ Journal.aspx)

- https://www.graceravlin.com

- conversations between the writer and Kristan H. McKinsey

- Bohmann catalogs, 1896 and 1899

- https://www.harpguitars.net/history/bohmann/bohmann1.htm

- http://www.harpguitarmusic.com/listings/hg-bohmann-3-08.htm

- Kaneville Township Historical Society- (also on Facebook) https://tinyurl.com/k9mya87d

- emails from Alta Ann Parkins Morris to the writer

Notes

- Kristan H. McKinsey is Director, Illinois Women Artists Project an initiative of Bradley University, Peoria, Illinois. https://illinoiswomenartists.org/

- links to purchase Grace Ravlin’s biography: https://www.blurb.com/books/10174882-yours-always-grace or https://www.graceravlin.com/

Kudos to Gregg and Bruce for bringing to light the amazing underreported (never documented) lives of these amazing musicians! Such a fabulous story on so many levels! Thank you again for working on this outstanding collaboration that tells us so much about the female contribution to our shared mandolin & guitar history. Sheri