From St. Louis to Philadelphia, from a typical American BMG duo to “real Mexicans,” this is the brief illustrated history of harp guitarist Harvey Ball.

As so often happens in the ultra-obscure and rarified world of the historical harp guitar, neither Harvey or the later “Ballo Brothers” would ever have come to light if not for a lucky “forgotten garage” find and a chance sighting. The sighting was in late 2021 when I stumbled upon an Instagram image of a new historical act with a harp guitar. Tracking down the source, I located one Michael Callan, who as a “traditional guitar fingerpicker” goes by the musical name of Easton Everett. His own find of the batch of six old photographs was one of those one-in-a-million discoveries. He says, “I found them after renting an old garage for rehearsal space, opening the door for the first time in 50 years and shining a flashlight on a pile of cobwebbed photos.” Unbelievable that they were still there undisturbed, the owner and any provenance long gone. A big thank you to Michael for licensing the photos to the Harp Guitar Foundation to share with the world.

We begin with “Isbell & Ball, String Musical Artists” from St. Louis, MO.

W. C. Isbell, on mandolin, gets first billing on this weathered cabinet card, while his partner on harp guitar is one H. A. Ball.

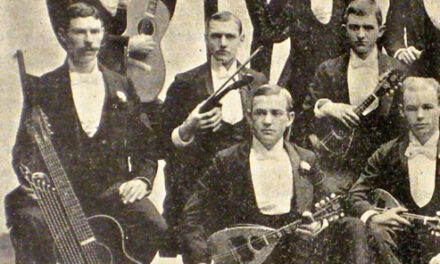

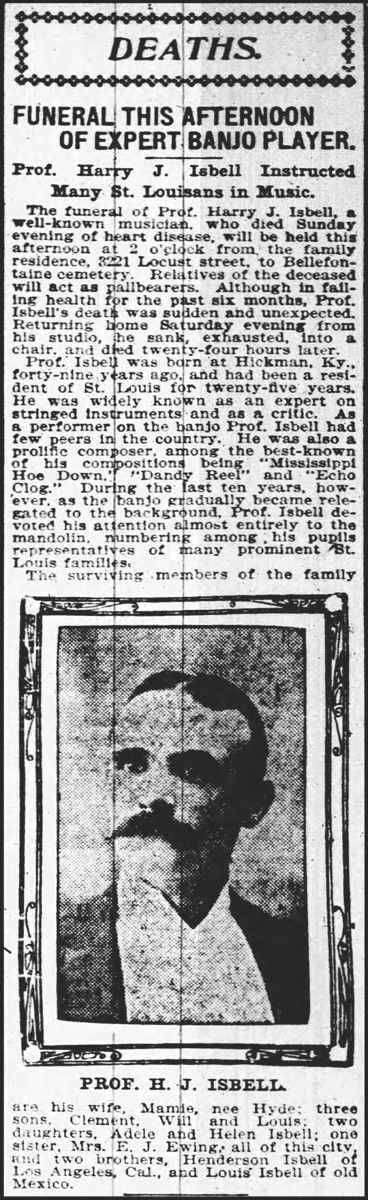

The only mention of them I’ve been able to find is (per Noonan’s BMG Bibliography) a notice in the March/April 1904 issue of F. O. Gutman’s Journal, where they are listed in reverse as “Ball & Isbell” in St. Louis. While nothing is yet known of Ball, who is absent from St. Louis directories, we do have information about “W. C. Isbell” (with expert help from the St. Louis Historical Society). William C. was one of six children of musician Harry (Henry) J. Isbell, who was the city’s best teacher of the BMG instruments – banjo, mandolin and guitar – and a well-regarded banjo player and composer.

Harry Isbell opened a music salon in St. Louis by 1885 at the age of 30, where he advertised as a teacher of banjo and guitar, and as a sales agent for S. S. Stewart banjos. The following year he was “sole agent” for Fairbanks & Cole banjos, and by 1892 was offering his own “Isbell Artist” banjo (built by Boston’s Luscomb firm, according to expert Jim Bollman).

Ad in the St. Louis Post Dispatch, Dec 18, 1892

Ad in the St. Louis Post Dispatch, Dec 18, 1892

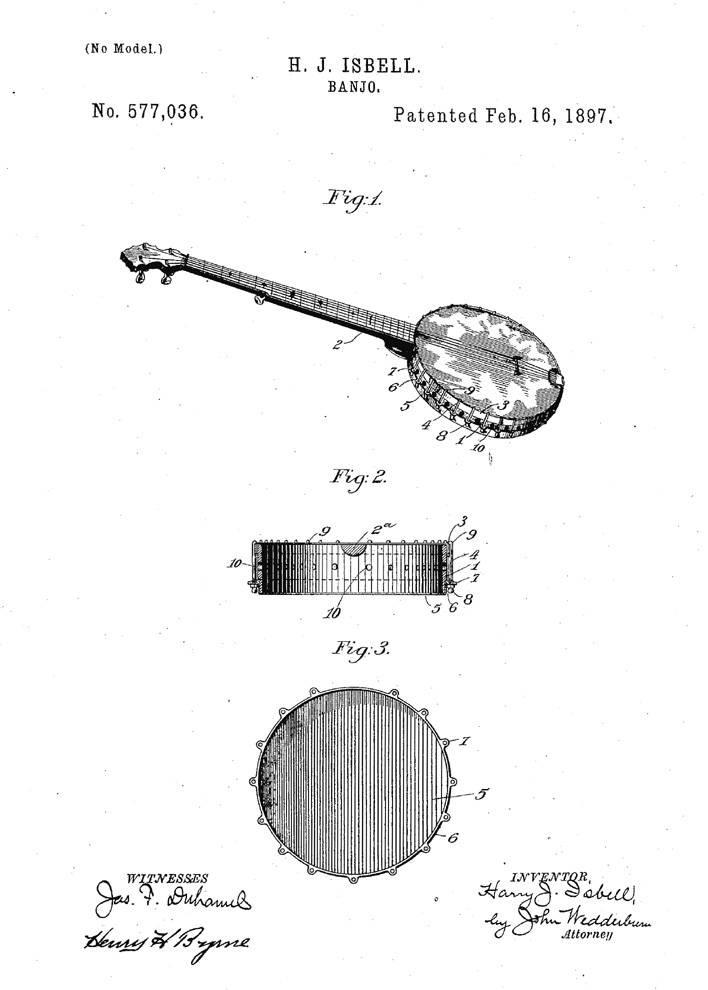

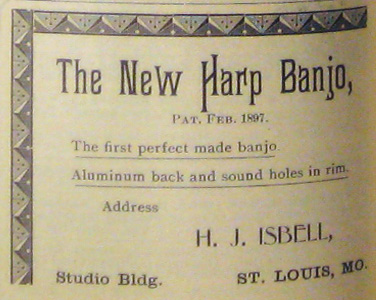

Four years later he applied for, and was granted, a patent for a new simplified banjo design that closed the back while including tiny soundholes around the rim.

This he called the “Harp Banjo” due to its alleged sonic enhancements. The patent got a full write up in the March/April 1897 Cadenza, which also profiled Isbell’s group.

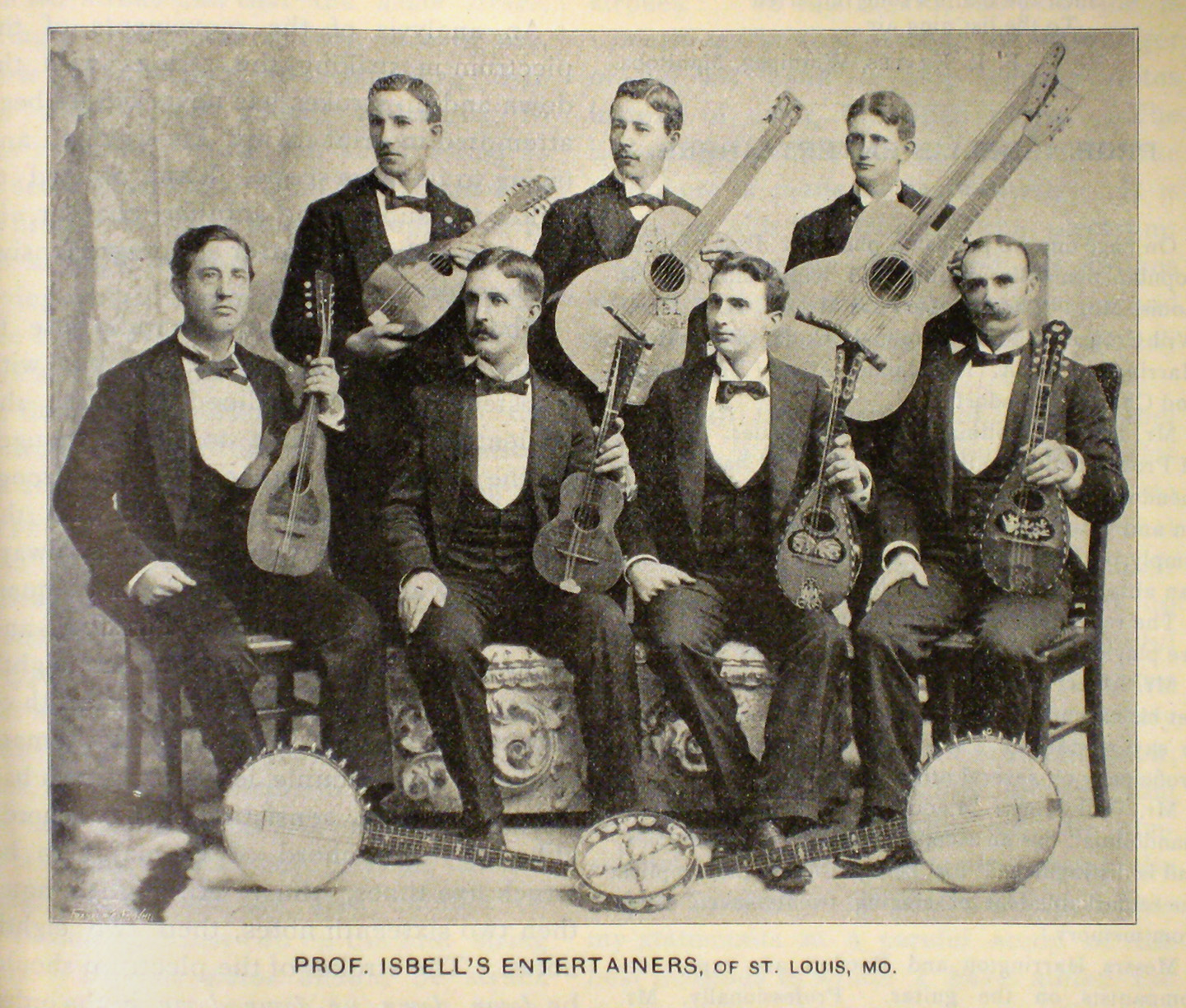

Above, one of H. J. Isbell’s many St. Louis BMG ensembles c.1897, with an interesting harp guitar model, and Isbell seated at right. By this time, he had switched mainly to mandolin. I was able to identify him from his 1905 obituary image below:

Of Harry J. Isbell’s six children, at least two formally went into the music business: Clement (born 1884) and William C. (born 1886). Both young men were listed separately as musicians in 1904 at their father’s address. I’m happy to report that young William was not involved in the 1903 incident where both Harry and son Clement attacked the music firm’s business manager William Steck with clubs after his refusal to accept Harry’s dissolution of their partnership (Harry’s revolver luckily not put into use) – the beating stopping only when the town’s citizens were able to stop it. Presumably, young William was elsewhere quietly practicing his mandolin. He would soon join one young Harvey Ball in a duo that was likely helped along by Isbell’s successful father.

There’s no telling when the above image was taken, though c. 1904-c.1907 seems likely (William would then have been between the ages of 18 and 21). Isbell’s partnership with Ball was short-lived, as he contracted meningitis and died at age 22 on October 22, 1908.

Before leaving Isbell & Ball, let’s take a look at Ball’s interesting harp guitar. Doesn’t that bridge look familiar? It did to me – so I shared the image with experts Robert Hartman and Benoit Meulle-Stef for their thoughts. They concurred: while not an exact match (it’s missing the two little “horn” extensions), it is otherwise basically identical to a unique bridge design used only by Chicago’s Larson brothers on three custom harp guitars which we believe were built around this very time frame (c.1901 – c.1912, but possibly closer together in the mid-1900s decade). Check them out:

While other luthiers did similarly decorative bridges, none were shaped specifically like these were. Again, it seems strange to leave the points off if doing the hypothetical build of Ball’s instrument. Nor does that simple conjoined headstock match any other Larson instruments (although it matches no American-built designs either for that matter; it seems to follow a simpler European design). A final clue is the dot marker on the 10th fret, a common Larson feature (though not necessarily a smoking gun). Anyway, all this is so far just interesting speculation!

Before his first partner’s death and likely having been instigated earlier by Isbell’s declining health, H. A. Ball had a new partner and a new partner, whose name so far remains unknown. They were already touring by June 7, 1908, the date of their earliest-discovered performance in Birmingham, AL.

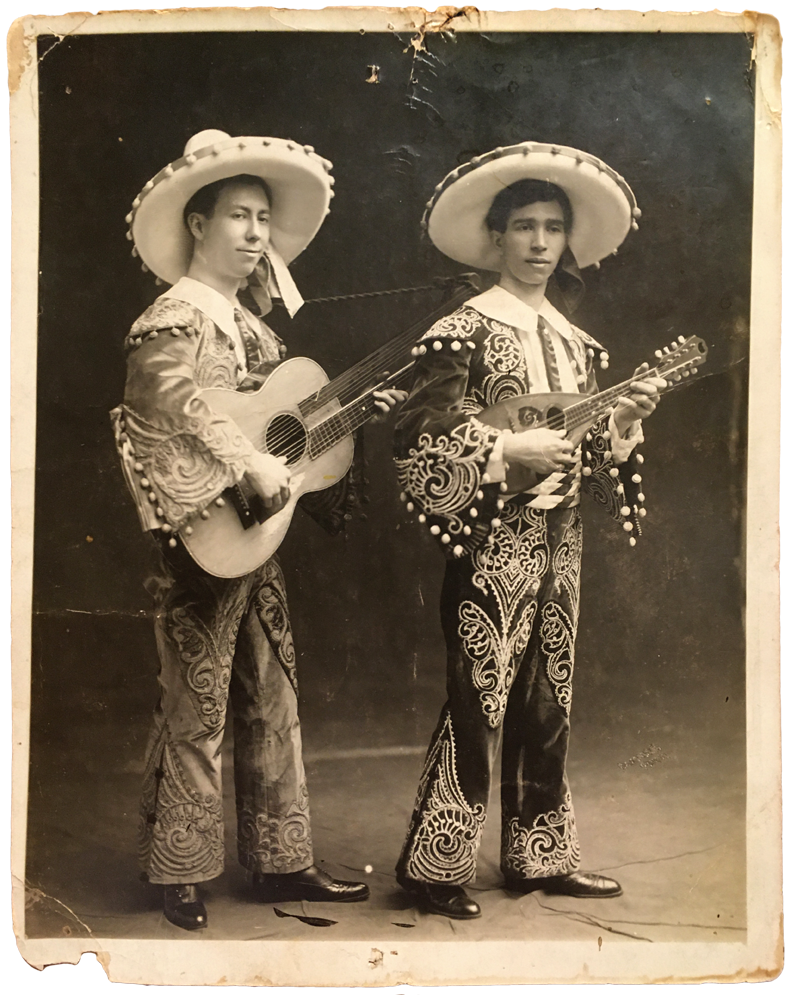

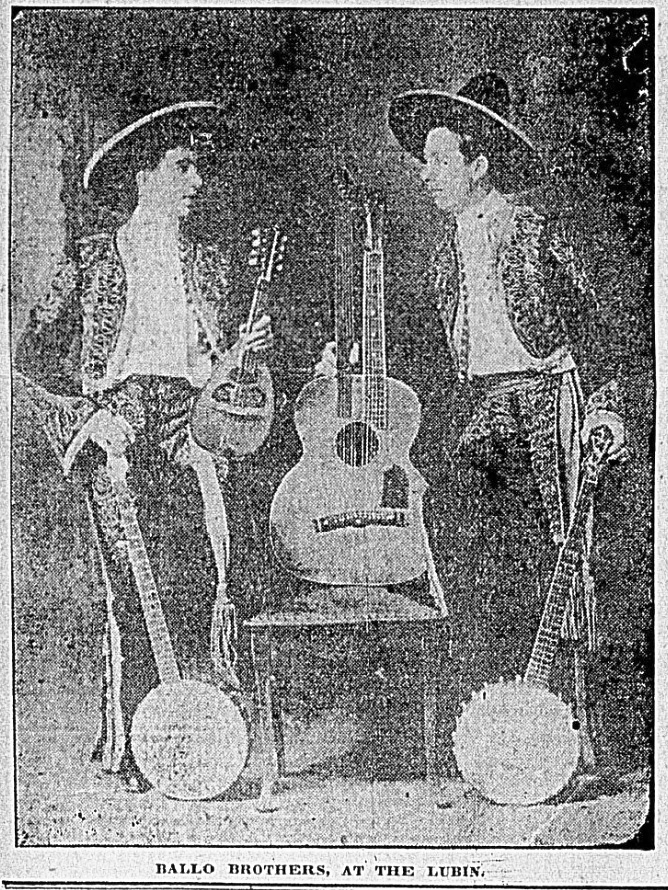

Perhaps sensing the more unique advertising opportunities of his partners’ ethnicity, Harvey Ball would alter his name and “adopt” his partner to become the “Ballo Brothers,” the “Original Mexican Serenaders.” Yeah, he looks about as Spanish as I do – perhaps the “direct-from-Mexico” costumes helped fool promoters, as the popular pair were said to be “the real sort of Mexicans, not the stage kind, and were official musicians to the President of Mexico, Porfirio Diaz” (Nashville Banner, July 28, 1908).

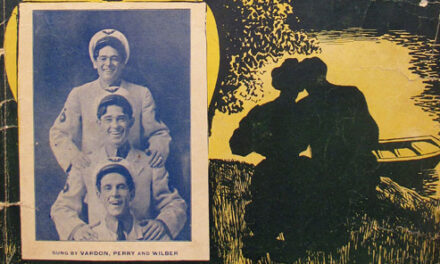

Like many professional BMG musicians, the “brothers” were proficient on all three – banjo, mandolin and guitar. Their newspaper reviews frequently mention the “high order” of their playing and “difficulty” of the selections, often singling out the “selections from Il Trovatore” on their classic 5-string banjos.

The photographic evidence – all taken at the Sommer Studio in Philadelphia (active 1904-1915) – shows them performing together on mandolin-banjos as well (referred to as “banjorines” by one reporter). One newspaper clipping mentioned their excellent “singing and dancing” in addition to the instrumental selections.

But once again, I’m equally curious about Ball’s harp guitar! Happily, two additional newspaper images provide fuzzy yet crucial details:

This image from an October 13, 1908, announcement more clearly shows Ball’s harp guitar – the heads, necks, pickguard (added onto worn area) and bridge.

Here, a June 19, 1909, clipping obscures the head, but shows the bridge well. Any candidates? Yes!

Benoit and I agree that the rare instrument is quite likely another example by an obscure Muncie, Indiana maker named C. Cochran. Two extant examples are known, here compared to the 3 images of Ball’s instrument (I show 2 additional potential Cochran harp guitars in historical images in this blog). Cochran’s bridge remains a unique design among American harp guitars as does the “squiggly” bass head design. The body plantilla seems to follow the style as well.

The “Mexicans” later played dress-up cowboys as well, and in this signed photo, we learn that H. A. Ball is “Harvey.” Naturally, he adds the “-o” for his stage name, even though he looks about as cherubic a Caucasian as you can get.

Now these instruments I can identify! For some reason, the Ballo Brothers may have thought that a hollow-arm harp guitar somehow looked more “Western Cowboy” than the double-neck style, so they went out and bought or ordered two then-brand-new Knutsen black-top instruments. Ball’s partner has a new hollow-arm Knutsen “harp mandolin” while Ball has a late Seattle-era harp guitar with the pointed lower bass bout.

More interesting is that the standard-size harp guitar has eight sub-basses – Knutsen’s record, and only the second instrument of his known with eight (the other, in my collection, has a standard scale length but a vastly oversize body). Though Ball is partially covering up his sub-bass headstock, what I can see seems to indicate Knutsen’s last evolutionary shapes, meaning c.1913-1914. While the last performance I’ve located of the Brothers was December 29, 1914, I wonder if Ball perhaps had this instrument on December 12, 1912, as that was the first (and only) time a newspaper mentioned the “guitar-harp.” My thinking being that the hollow arm harp guitar variant would have appeared much more unusual to the public than one of the double-neck varieties, perhaps instigating (with the oft-seen backwards term) the harp guitar mention?

Thoughts and additions to the lost story of these two unique Harvey Ball duos are welcome!

Thanks to Michael Callan, Jim Bollman and Magdalene Linck of the St. Louis Historical Society.