Last week I shared some of the photos I took in the MIM galleries during our American Musical Instrument Society conference.

Beyond the events of AMIS, I was anxious to visit the MIM once more (my last visit was in 2019), as there was a group of instruments I had been trying to track down for ten years!

And this story is not yet complete. But getting there…

We begin in May 2013, when I was invited to speak at the first Harp Guitar Festival in France. After a solo vacation throughout the country, I finally met up with a couple of my harp guitar colleagues in Le Mans on June 3rd. Now six strong, we continued to stroll through the charming town, when suddenly, someone spotted a lyre mandolin through a shop window!

That’s John Doan and Benoit Meulle-Stef peering into through the glass like cats outside a seafood store. It wasn’t actually a shop, it was a small private museum, and contained a collection of rare guitars and mandolins.

Only a few of them were visible from the windows. One of our group later did a search and found two more photos of the collection:

Note the turban, kobza and, on the right, a Harpolyre next to the lyre guitar.

Around this same time, before I had a chance to try and track the owner of this fascinating collection down, I found myself once again at an AMIS meeting, where a well-known European dealer shared with me his private notebook. In it, were photographs of the entire mystery collection. It belonged to one Raymond Zéliker, and my friend was now shopping it!

I remember seeing a plethora of rare and wonderful instruments, including one impossible find on my bucket list (even rarer than the Harpolyre). Unfortunately, the collection was only being offered intact and was far beyond my means (though, in hindsight, probably a bargain).

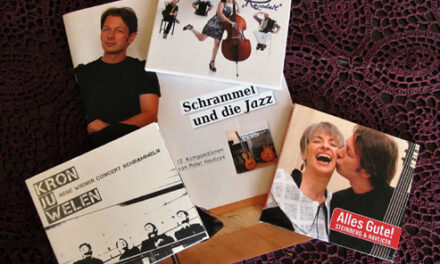

Doing some more googling, I found a few articles about Zeliker (above) and his creation of a local mandolin orchestra.

He also shared his collection at occasional events (above taken in 2012 or 2013).

At the next AMIS meeting, when I could query my friend, he said that the collection had been sold and shipped off to the MIM in Phoenix. Well, maybe now I’d have a chance to see it!

Not so fast…

It seems the collection had gone AWOL. I don’t know the particulars, but the crates somehow went missing for some time (months or ?). Whether customs, paperwork, or human error, no one seemed to know anything about where they were, or when and where they might be turn up!

I learned nothing further when I visited the MIM in 2019, but finally, on November 6, 2020, the museum posted the article “Rare Mandolins from the Zéliker Collection Now at MIM”!

At last! (I never did discover what had happened; perhaps it better not knowing!)

And so, in May 2024, I finally got to see … some of the collection. It seems that the harpolyre – and possibly many other instruments – were not included in the sale. When I inquired into the harpolyre, neither the European nor American Gallery curators knew anything about it.

As for what they do have, one has to go hunting through the Galleries looking for them, as the museum has not yet catalogued them for the public. And so, I did!

Frustratingly, the signs do not include “Ex-Zéliker collection” – the only clues I had were the date of 2020 and “Gift of the Robert J. Ulrich and Diane Sillik Fund” (Ulrich being the museum’s founder and continuing benefactor), and accession numbers starting with “2020.31.” However, I was in a rush and did not always take closeup photos of all the candidate labels.

First stop: those two kobzas I showed in my last post? Thay are all but identical, yet neither sign seemed to indicate ex-Zéliker. And the instrument on the right matches the one in Zéliker’s original case in France.

The torban also came from France, as the sign signifies.

Similarly, the mandola just above it (accession # 2020.31.23).

This rarity is labelled “…fine Ukranian arch-cittern…18th c.”

A more traditional cittern

This fantastic trio of citterns includes an original MIM acquisition from Claremont, California’s Fiske Museum at bottom right. The other two are ex- Zéliker.

Labeled “Swiss cistre mandoline.” Note the single floating bass course, often seen on German waldzithern. Reader Norbert Feinendegen kindly emailed after seeing this, saying ” Your comment is very much to the point, for this instrument is not a Swiss Halszither but a Thuringian Waldzither that was built by Friedrich Ludwig Möller in Suhl/Thüringen, probably between 1860 and 1900. Some information about him and images of some of his instruments can be found on pp. 38-43 in this document.” Thanks, Norbert! That PDF article is fantastic. I’ll have to get that translated asap…

The stringing (courses) on this wonderful “Swiss halszither” are difficult to decipher.

Don’t quote me, but the theorbo and mandolin in the center of this group may have come from Zéliker.

This “archlute” almost certainly did.

Zéliker’s collection concentrated on mandolins, and here are many of them! All but three in this display in the Italy section appear to be from his collection. Exceptions are the curious piccolo lyre mandolin (from Canada’s Music Treasures some years back) and two from the Fiske (the one below the lyre mando and the large “mandora” at bottom).

And now – for me – the prize of Zéliker’s collection. This instrument (2020.31.57) is about the sixth (?) specimen I’ve tracked down of this misunderstood “double-neck arch-guitar,” which was once not all that uncommon. With (until quite recently) zero information available on it, some curators deemed it an “arch-cittern,” likely due to its many superficial similarities to the Renault arch-cistres. However, the present instruments all have pin bridges and gut strings. The fretted necks contain six single strings – though half the specimens have five single strings, as the instrument appeared during the gradual switch-over from five course to six! (You can see examples of both in my article “The Earliest Harp Guitars.”) The second neck was obviously intended for a higher tuning; despite its scale ratio, it was meant to be an octave higher. Each neck – with its own individual floating basses – would then be independently be played as a harp guitar.

I hope to one day do an article on the inventor and builders (and date and tuning) of these wonderful instruments. For now, we can enjoy the fascinating design and construction of the first one in the States!

There are undoubtedly more ex- Zéliker instruments scattered throughout the MIM’s galleries, though whether that includes all 64 is unknown. I hope to eventually get a list from my contacts there.

I’m thrilled that these instruments are available to view in the U.S., though lament the fact that once again, we’ve lost the “story” here. That being the life and career of Raymond Zéliker, along with a thorough cataloguing of his original full collection in photographs, descriptions, history and the like. I haven’t seen anything to indicate that he ever produced such a document. I don’t even know if Zéliker is alive, or if any family or friends remain with the resources to create a more lasting legacy than my small snippet here.

Much like I continue to try to do with my own collection and occasionally others (Walter Erdmann’s being a good example of a “too-late” attempt), I hope the hundreds of other collectors out there will consider documenting and sharing their own musical legacies.

Next: It’s Dawg, himself, with MIM’s “Acoustic America” exhibition!

Totally cool, Greggster!!

I love the scroll-pegheads on those arch-cittern-things! I’m always impressed, looking at historical stringed instruments, by what incredible variety (and skill and creativity) is displayed. And I’m always puzzled by how we seem to have lost a lot of that in modern lutherie (and music) …. where did that change happen, and why?

I continue to do my best to correct the situation… but I’m only one (old, slow) guy. Thank goodness you’re there, inspiring the troops to wake up and have fun!!

Thanks as always!

Fred