|

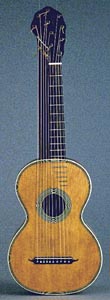

The Lacote Décacorde and Heptacorde: by Gregg

Miner |

|

|

It was with great sadness that I learned of the death of guitar expert Bruno Marlat in December 2019. Though he did not contribute directly to this article, his work is quoted generously throughout. After his death, his wife Catherine finished and published their monograph on Lacote, which is essential reading before or after reading my own article. I will not be duplicating their book material here, only drawing from it. Additionally, my September 2025 update also draws from the just-published Dictionary of French Guitar Makers, by Catherine Marlat & Erik Hofmann. My own article here serves as a more thorough Appendix on all of Lacote's non-six-string guitars, along with similar instruments by others and the modified instruments of Napoléon Coste. Please consider this page an permanently archived "work-in-progress," with plenty of discussion and speculation - one in which I rely on input from many different sources, all better informed and experienced than I (though often, sources who may offer very different opinions). These sources include scholars of every stripe, along with luthiers, dealers and collectors. Introduction Historians, Collectors, Luthiers and Players of "classical" and "early romantic" guitar may be nonplussed by my title above. Lacote, the renowned Parisian luthier certainly never made "harp guitars," did he? Well, it's all a matter of semantics and perspective (actually, the answer to the title is "All of the Above"1). Those familiar with my Harp Guitar Organology will recall that the "harp-guitar" term wasn't applied to instruments with floating sub-bass strings until the 1890s in America. In Lacote's time, multi-course (multi-string) or extended range guitars were most often simply called "X-string guitars" ("X" being either 7, 8, 9 or 10). In contrast, Lacote's instruments were specifically named the Heptacorde and Décacorde.2 Regardless, none of these multi-string guitars were ever "classified" for purposes of organology as we do today. While Early Romantic Guitar historians may refer to the Lacote floating dropped-D string instruments below as "7-string guitars" (when not using the specific historical French name "heptacorde"), the term allows for no distinction between this simplest of recently-classified harp guitars and other standard, fully-fretted-across-the-neck 7-string guitars - ergo my choice (and strong suggestion) on also referring to these instruments today as 7-string or 10-string harp guitars (particularly of course in the context of this web site).3 While the majority of Lacote instruments are 6-string guitars, a significant number of these extended range versions were made. Unfortunately for researchers, there are many instruments that were later modified into having seven strings or more. Other "original" instruments shown below may be seen as suspect or at least unproven by one researcher or another (based on the responses I have received from various experts). Pierre René Lacote Widely considered one of the finest French luthiers, if not the 19th Century's most important French guitar maker, there was little biographical material about Pierre René Lacote until the Marlat book.4 By the age of twenty, he was working as a silver-smith for a merchant. Conscripted into the army, he was declared unfit and discharged the next year. It would be a dozen years since the 1805 military census and the first evidence of his lutherie in Paris. The Marlats postulate that Lacote may have entered luthier via first doing silver-smithing for lyre guitar for makers such as Lejeune, Ory or Pons. He would subsequently apprentice "under Pons." Of the many males in the extended Pons family, the Marlats deduced that it was Antoine who Lacote would apprentice with, not Joseph as has previously been reported. The first ten years of Lacote's career, addresses and and such are discussed in the Marlat book, and don't relate specifically to my topic. I'll include this simple overview from my original article: While credited for many innovations to the guitar, most of these can be considered "improvements" to previous inventions, such as new bracing, second soundboards, enharmonic frets and improved friction tuners. His one true innovation was his sophisticated encapsulated machine tuners. He worked closely with the best guitarists, including Sor, Carulli, Aguado and Coste, to create optimum instruments to meet their requests. He received awards for his guitars in 1839 and 1844 in the Great National Exhibitions (each time for his heptacorde). Lacote's birthplace and date of death were not resolved until the Marlat book unveiled the findings from their years of research. We now know he was born on February 5th, 1785 in the small central France town of Bellac. His father Pierre Parinaud would at the time of his marriage become Pierre Parinaud delacôe (or dit Lacote [alias Lacote]). As the Marlat's explain in their book, his son (our luthier) would choose to go by Pierre René Lacote (or just René Lacote), leaving off the circumflex above the "o" - thus, I have had to go back through my article and remove every instance of that "ô"! Due to economic realities, Lacote relocated to Versailles in 1848, where, to supplement his guitar orders, he opened a linens and haberdashery shop, which he left to his wife to run. In 1859, Lacote closed this shop once both of his children had left home, moving to other shops to continue his occasional lutherie with his partner Eulry, who would pass away in 1864. Lacote would pass away in his newest home on February 10th, 1971.4b

Patent Configuration By "patent configuration" I mean those strung 5 open and 5 fretted, with 3 dital sharping levers. (In many cases, I am unable to tell whether the ditals were originally there or not, or are just missing.) The Marlats further stated that (stringing aside) around 1828 the headstock became straighter, without the obvious protruding bass side lobe. I myself actually see many different shapes, not just a lobed and straight version. I would appreciate others' help in putting these into a better chronology (with circa dates to match).

Non-Patent Configuration |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

I think everyone agrees that the earlier bissex headstock was the inspiration for the Carulli/Lacote Décacorde. It even had similar sharping levers. In this light, how much credit is really due Lacote for the Décacorde design? Naderman, a harp maker, created this unique instrument that some consider the first dated "harp guitar." With its lute-shape and staved back, I consider it a hybrid harp guitar-like invention. See also Mixed Family Hybrids & Other Related Forms.

|

|

Naderman

Bissex 1773 Collection: Cité de la Musique |

Napoléon Coste and the Heptacorde

A good introduction to Coste and his music is the

complete

preface by Brian Jeffery (1982) in La Source du Lyson, op. 47 According to Bruno Marlat (in the liner notes to Brigitte Zaczek's 2005 CD Romantic Guitar Vol. II, as translated by Steven Edminster), as early as 1835 "the use of a seventh string puts in an appearance" in Coste's opus 5, "Souvenirs de Flandres" (published by Lacote). Marlat astutely noted that "even though this may simply have involved the exploitation of an older idea, people referred to it as an 'invention'." Marlat cited additional provenance, including that Lacote "received a prize in 1839 for a seven-string guitar which was described as 'perfectly crafted, having in addition a very beautiful tone quality.' At the next fair, in 1844, he presented 'several heptacorde guitars which are perfectly crafted and have a beautiful quality of tone, instruments which were awarded top ranking positions in the contest'." Marlat concluded (as would I) that the specific name "heptacorde" came from Coste since "we read in the appendix on the seventh string which he added to his 'N. Coste’s New and Enlarged edition of Sor’s Guitar Method' the following statement: 'Some years ago I arranged to have built in the workshop of Mr. Lacote, a maker of stringed instruments in Paris, a guitar designed to yield a larger volume of tone and, above all, a more beautiful quality of tone. [….] I called this new type of guitar a Heptacorde'." This then, is our proof on the origin of the heptacorde, if we take Coste at his word. Unfortunately, Coste also claimed (in the introduction to his "25 Etudes de genre pour la guitare, opus 38" per Marlat) that "This improvement was immediately adopted and taken further in Vienna, Austria." This claim seems rather boastful, as numerous players and builders in Vienna and elsewhere had been experimenting with 7, 8, and 9-string guitars from as early as 1809 and possibly before. ADD MOLITOR FOOTNOTE OR ? Early Heptacordes There is not yet full consensus on how many of the surviving c.1835-c.1841 heptacordes are fully original. Marlat wrote: "The first seven-string guitars of Lacote differ little from his six-string models. The additional string is fitted in the theorbo manner as described by Coste: 'The seventh string, much longer than the others, is fitted at a certain distance outside the neck of the instrument and requires no change in playing technique'. In two of the three instruments we are familiar with, the fingerboard has five additional frets – 22 instead of the usual 17 – and reaches over the edge of the sound hole, extending the range to D5. An instrument of this kind, held gracefully by an elegant young woman, provides the frontispiece for the Sor/Coste method. A photograph of Coste...shows him posing with exactly the same model." Below, I show first the illustrated model and Coste's early specimen that Marlat described. The next few extant instruments I show are believed to be authentic pre-1850 heptacordes. They are roughly arranged by body shape and other features (with help from others). Thus, the listed owner's circa dates might need some tweaking. Some of these have been discovered quite recently ("Ben Mc"s, Hofmann's with its fascinating curling headstock, Renard's, and Coste's original instrument from Marlats' book). The Verrett specimen (since sold) and the Westbrook are similarly believed to be original. The last two have long since been established as "modified."

Later Heptacordes Soon after Lacote again won bronze for his heptacordes in 1844, more striking new features appeared, some once again instigated by Coste. As described by Marlat: "The shape of the body is broader with a less narrow waist than the usual Lacote designs; the fingerboard has 24 frets covering four octaves and the lower part rests on (standoffs) and is not in direct contact with the soundboard; the strings pass over the bridge and are fastened to a tailpiece at the end of the body; a bar of maple is glued on at two contact points parallel to the first string, perhaps as a kind of support for the little finger. The whole instrument seems to be designed with a view to allowing its soundboard to vibrate as freely as possible." Coste's Bridge System Enters the Picture Marlat continued, "This description could well apply also to a Lacote heptacorde kept in the Paris Museum of Music (shown below) where a handwritten note tells us that this is 'the favorite guitar of Mr. Napoléon Coste. The bridge has been applied by the remarkable composer and professor himself'. It would thus seem that Coste was not only the inventor and designer of this bridge/tailpiece system but actually built it himself." This "smoking gun" bit of provenance (that the unique bridge was built by Coste) stirs up a secondary topic and ongoing discussion/study involving Lacote instruments. Specifically:

I already mentioned above that some experts are still not positive that the extant early early heptacordes are all fully original. I now ask the question again regarding the later heptacordes. Are they original"? Can any be considered original, unless shown that Lacote himself installed the specialized Coste-style bridge system when new? How do we resolve this? As I discuss shortly, perhaps we can't.

|

|

|

Lacote Heptacorde, all original, not modified by Coste, c.1845-c.1849 (Bruno Marlat's "smoking gun" specimen) All four images above show Coste's second known Lacote Heptacorde throughout its life. This is the instrument with Petetin's handwritten note stating the bridge system is "Coste's own invention and work," which is likely not true. As the Marlats point out in their book, this instrument has no string holes in the top under the bridge, verifying that this Coste-style bridge was original to the instrument. It furthermore shows refinements pointing to Lacote himself being the original luthier of its components. Their conclusion is that Petetin was in error when he wrote his inscription "at least thirty years after the instrument's construction." ″Guitare favorite de Monsieur Napoléon / Coste. le chevalet a été inventé & / posé par ce remarquable composi- / teur - professeur. Après la mort de celui-ci, cet instrument a été / cédé à M. Petetin par un des / amis de M. Coste en 1883″ * * Etui en bois peint en noir garni de textile rouge * Etiquettes de l'étui : ″Fragile / M. C.″ (manuscrit) ; ″Eugène Petetin″ Collection: Cité de la Musique E.995.26.1 |

|

Coste Modified Bridge and Tailpiece System I am, frankly, out of my element here, and rely on the research and expertise of others, where I do not always find consensus. One thing seems certain. If Coste owned all the instruments that we find with "his" bridges, then he was quite the guitar collector! Add Van Viet footnote Coste likely also installed his modifications on instruments destined for his pupils or other patrons, and perhaps the "Coste modification" was duplicated by others. The question of whether Lacote himself installed such systems for Coste (and which specimens, and when) is not easily answered. Did Lacote - with Coste's input - in fact build the first such prototype? Some evidence points to yes. As for all the many other instruments shown below (including many makers besides altered Lacotes), Marlats give this quote from Coste himself, speaking of his vast instrument collection: "I can still undertake some of the modifications on my instruments. I have a student who assists me a great deal in this. I have a superb collection of guitars that have undergone such transformations." Alex Timmerman speculates that Lacote did perhaps construct some of these bridges and was "among the first" to do so, explaining that "the original Lacote guitars I have seen with this bridge/tailpiece type show good craftsmanship." Sinier and de Ridder do not believe that Lacote made these modified bridges himself as none of these features are in "Lacote's manner, style, techniques, acoustic principles, choice of wood, varnish, etc." While acknowledging the possibility that Lacote may have constructed the first one or more custom bridges suggested by Coste, they believe that Coste otherwise made all these bridges and tailpieces himself. They are convinced that both the concept and craftsmanship on the examples pictured in Coste's photograph and surviving specimens is Coste's own. Besides the finer details, they point out an obvious clue - that they have never heard of any Lacote guitar with an "original 'Coste' bridge" that has no holes in the top - i.e.: the holes from Lacote's original pin bridge are always present. However, an exception can be plainly seen in Kresse's specimen, seen here. They suggest that Coste modified such guitars for his own use and for the many students, friends, and customers that he had throughout his long career. And indeed, there are far too many such instruments for Coste to have owned them all! Bruno Marlat: "While it may seem unlikely that all these modified instruments actually belonged to Coste, one might well imagine that the teacher had a hand in modifying guitars intended for the use of his pupils." James Westbrook: "No doubt Coste had a large amount of instruments, but also a massive following of disciples that needed to acquire 7-string instruments one way or another." Bernhard Kresse (regarding his 1855 specimen): "There remains the possibility that Lacote did 80% of the work and left for Coste the making and installation of the bridge, tailpiece and finger rest. Possible but unlikely. These additional parts of the guitar are made with the same accuracy as the rest of the instrument. Further, the varnish doesn’t show any difference in color under fluorescent light. By the way, the construction of the neck and fingerboard, its final calculation of thickness, respecting the right angle and the difference of treble/bass side requires an early presence of the bridge during the construction process." Clearly, we can see from the above discussion (and more below) that there is little consensus on this question - partly because of differing conclusions from the analysis of the same instruments but also largely due to the fact that there are so many different and inconsistent specimens that are being referred to. The only way I can see to resolve it would be to get all of these instruments and experts into the same room and start comparing instruments and notes! Sinier and de Ridder believe that Coste also sometimes modified the fingerboards and the heads

of certain instruments.

|

Collection: Cité de la Musique |

Napoléon Coste seems to have modified nearly every instrument he acquired. Here are a few additional non-Lacote instruments known or suspected to have had the "Coste touch." At left is the wonderful "baritone" guitar Coste is pictured with in the famous photo, now in the Cite de la Musique museum. Note his same bridge and tailpiece system and the elevated maple finger rest -elongated as needed! It is not labeled, and no one has conjectured as to the builder. Sinier and de Ridder are convinced that it was built by Coste himself At left (middle) is an instrument from Coste's estate that he also modified. The maker's name, Olry, is handwritten on an affixed label.10 Originally, in their book, Françoise de Ridder conjectured that this Olry might have been the same maker as the Eulry heptacorde above. Their reasoning was exacerbated by the late Matanya Ophee, who told them (after their book was published) that "the Russian pronunciation of both Eulry and Olry are the same (and similar in French), and that it was therefore a transcription error from oral to written language." See La Guitare (Sinier de Ridder), p.55-56. It is now confirmed that this instrument was built by Louis Olry (1808-1866) himself - not to be confused with Nicolas Eulry, who's instrument is seen directly below.11 At right is a Schenk bogengitarre (in the Brussels Museum), one of the well known hollow arm harp guitars that inspired Mozzani. It has a replaced Coste-style bridge as well. The conclusion some jump to is that Coste owned and played it as well, but as stated by the many experts on this page, there is usually no way to know - and we doubt Coste could have owned all of these! About the Schenk, Françoise de Ridder (in the Guitar Summit forum) wrote: "Without any doubt, Coste made this bridge, and you can see the two little pins (that) supported the missing piece of wood for the finger (rest)." Alex Timmerman replied (also in the forum): "The Brussels Schenk guitar now shows a bridge made out of two saddles on either side of (what used to be) a tie-block through which the strings are lead towards a tail-piece where they are fastened. The finest examples of this bridge design, are of course seen on the guitars made by Lacote himself. The idea of replacing the old pin-bridge could be for reasons of spreading the tension that is caused by the extra added strings on Bass guitars. Lacote might have been among the first to install this kind of maple 'bridge/tailpiece' model on his bass guitars. What I can add to this is that among other things the bridge (à la Coste) on the Friedrich Schenk guitar at the MIM in Brussels is again not made to the high quality like those of the same type seen on the Lacote guitars." In 2008, a 6-string Lacote-style instrument appeared that was built by Valance and modified later - again, possibly by Coste (below left). Additional images In 2017, another Valance was seen in the Paris shop of Arguence Lutherie, which is now in the collection of Eric Mry (at right). Note its headstock; was this also a modification, or was it an original 7-string? Perhaps the clue is that is also has the same Coste-style modifications. Besides my obvious fascination with the harp guitars, there are a host of other important and fascinating Lacote innovations that can be seen in the Marlat book - including Lacote's custom, enclosed tuners, a double soundboard, and adjustable micro-frets for each string!

|

Schenk, modified Collection: Brussels MIM |

||

Olry, 1850 From La Guitare (Sinier de Ridder) |

||||

Valance, Mirecourt, c.1850, 6-string, modified Collection: Sinier de Ridder |

Valance, 6 or 7 originally, modified? Collection: Eric Mry |

Sources / Special thanks / Expertise (pers. comm.. or indirectly): Erik Hofmann, Dave Evans, Bernhard Kresse, Bruno Marlat (indirectly), Benoit Meulle-Stef, Paul Pleijsier, Daniel Sinier and Françoise de Ridder, Alex Timmerman, Len Verrett, James Westbrook, Cité de la Musique, Brussels MIM, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, European and American Musical Instruments (Anthony Baines), Fernando Carulli: Méthode Complète pour le décacorde, nouvelle guitare, op. 293 (reprinted by Studio Per Edizioni Scelte) Footnotes 1. Multi-string (or my preference, Multi-course) Guitar is a commonly used term for guitars with more than six strings - yes, it is technically illogical, as all guitars have "multiple" strings. Extended Range Guitar may be a little more logical than the previous, though is also unspecific. Bass Guitar is scholar Alex Timmerman's preferred vernacular for guitars with extra bass strings - much like my own Harp Guitar, which today most consider both vernacular and a newly defined and classified organological term. Please note that none of these four terms were used historically, and all have one detractor or another. 2. Yes, the literal English translations would be "seven-string" and "ten-string" respectively, but in this case I believe that the guitar community agrees (by mutual, if unspoken, consensus) that the French word for each of these newly-invented instruments acquired a new meaning as a "multi-language specific name." Personally, I find this another fascinating semantic topic that has yet to be addressed or discussed in our world(s). 3. As most serious readers know, I prefer using "course" in place of "string." (seven-course, ten-course) 4. Again, I don't duplicate the Marlat book material here, I only draw from it. The first thing they clarified was that the luthier's name was Pierre René Lacote, not François René Lacote (or René François), as was once stated by many guitar historians. 4B. As James

Westbrook once pointed out, "One person (probably Bone, or some

violin dictionary) wrote the date of Lacote's death as 1855 and

everyone took it as gospel, which I know is incorrect. For decades then,

people either wrote that or "after 1855," which, while accurate, wasn't

much help!

5. Per Marlat, the décacorde

was Carulli's idea, that he brought to Lacote. Lacote devised the sharping

dital levers and design, including the full length cut out trough for

the thumb. Curiously, only the C, F and G strings of the five basses

would have sharping levers for different keys. Carulli and Lacote

jointly submitted the patent on Oct 31 1826, which was granted Dec 15 of

the same year. I They exhibited the instrument at the Exhibition of

Products of French Industry in 1827 but it went unrewarded. In 1831 a

Paris teacher Mr. Amory placed an ad extolling its virtues - this was

its very last gasp. The "failed" invention nevertheless brought Lacote's

name to both amateur and professional guitarists.

6. In fact, I

am continually surprised to find that virtually every guitar researcher

and writer lumps the décacorde

in with other "10-string guitars," when it

is such a distinctly different, specific instrument. It is casually

lumped in with the original Viennese 10-string harp (bass) guitars, and

even more disconcertingly, with today’s’ fully-fretted 10-string

guitars (in all tuning configurations, Yepes or other) – as if the

simple coincidence that it has ten strings is proof of some sort of

ancestry or commonality. I find this as laughable as all the

Wikipedia entries that try to “define” various guitar "types" simply by

number of strings - but was encouraged by the author of the Yepes section

of the Wikipedia "10-string guitar" entry, who succinctly states, "One

cannot consider as synonymous (just because they have the same number of

strings) different instruments that do not have a commonly accessible

original repertoire, that approach music through different performance

practices (different techniques, especially with respect to the use of the

7th string, open and stopped strings), different instruments that are not

only tuned differently but strung differently. The true modern

10-string guitar is as little defined by its number of strings for their

own sake, divorced from their singular tuning, as a piano is defined by

its number of keys."

7. In his

method, Carulli pointed out that his instrument was designed for

amateurs, being easier to play chords "to accompany romances or

ariettas." He also highlighted the tone of the open strings, saying that

they helped increase the "instrument's volume nearly by half and at the

same time renders it more harmonious and richer than the ordinary

Guitar."

I further noted that the inventors seem to

have rarely said “than the regular or six-string guitar –

just “Guitar,” to further demonstrate that their

décacorde was a different

instrument than the now-standard 6-string guitar.

8. It is a complete coincidence that Carulli’s and

Yepes’ instruments were both ten-string guitars. Yepes’ was founded

on a much different (and obviously more acceptable) concept, with a

completely different tuning configuration, which just happened to have the

exact range (down to C) required for the Carulli pieces. However, the

pieces would have a somewhat different sonority when played on the two

instruments, due to the different open strings.

9.

To this day, the Wikipedia "Harp Guitar" entry includes Sor, and there

seems to be little we can do about it!

In fact, other than

(rather ironically) his famed use of the harpolyre, Sor appears to

have been a critic of extra strings, writing in his Method:

“à employer toutes les facultés de la main gauche pour la mélodie

(…) fait éprouver aux guitarists de grandes difficultés lorsqu’il s’agit

d’y ajouter une basse correcte, si elle ne se trouve dans les cordes à

vide (…). On a cru remédier à cet inconvenient en ajoutant à la guitare

un nombre de cordes filées, mais ne serait-il pas plus simple

d’apprendre à se server des six? Ajoutez des ressources à un instrument

lorsque vous aurez tiré autant de parti que possible de celles qu’il

vous offer; mais ne lui attribuez pas ce que vous devriez vous

attributer à vous-même.” (“By employing all the possibilities of

the left hand for the melody (…) makes the guitar player feel a great

difficulty when he has to add a correct bass when it is not on the open

strings (…) it has been tried to correct that by adding to the guitar

several bass strings - but wouldn’t it be easier just to learn how to

use the six? Add resources to an instrument when you have used all the

ones it has to offer. But don’t project on it what you should expect

from yourself.”) 11. Eric Hofmann, pers.

comm. 9/24/25. 12.

From Dictionary of French Guitar Makers (per

Eric Hofmann, pers. comm. 9/24/25).

9/25/2025:

Added a new 1830s heptacorde specimen (courtesy of Ben Mc.) and new

photos/ownership of Len Verrett's original heptacorde (courtesy Jeff

Wells). Clarified the past confusion on makers Olry and Eulry.

11/10/2024: At the encouragement of Erik

Hofmann and Catherine Marlat, I fully revised and rewrote this article. 10/10/2021:

Added new specimens: an early heptacorde with scroll headstock! Also what

looks like another early non-Lacote 6-string modified by Coste into a 7, an

unmodified 1846 heptacorde, and new images of the late Dave Evan's 1842 Heptacorde,

now restored (courtesy of new owner David

Jacques, acquired from Dave's estate). |

||||

|

|

|

If you enjoyed this article, or found it

useful for research, please consider making a donation to The

Harp Guitar Foundation, |

|

|

|

All Site Contents Copyright © Gregg Miner,2004-2025. All Rights Reserved. Copyright and Fair Use of material and use of images: See Copyright and Fair Use policy. |