|

Special Combined Feature:

by

Gregg Miner, July, 2008

|

|||

|

|

Chapters |

|

|

|

Special Combined Feature:

by

Gregg Miner, July, 2008

|

|||

|

|

Chapters |

|

|

|

Introduction Luckily, Albert Shutt had a perfectly good day job in the music business that remained rewarding throughout his life. Unfortunately, despite his best efforts, his unique instrument inventions and designs – which were in many ways precursors to or improvements on the much-ballyhooed Gibson instruments – never had a chance of catching up with the more famous company’s popularity. Thus it was that Albert found it necessary to multi-task throughout most of his career, a talent at which he excelled. He tirelessly taught music and various stringed instruments during the day, built his new instruments in the evening, and composed music and lyrics as he found time. In addition, he arranged music for, practiced and performed with, and often conducted various musical ensembles. |

| This article is the result of a lot of information gathering from Shutt instrument owners, but mainly from material and information supplied by Jack Shutt, the grandson of the great, unsung Albert Shutt. | |

| The Shutt family, circa 1930: (standing from the left) Albert, Melvin (Albert's son), Myron, Melvin’s brother; (seated from left) Cathern Ann and Simon, Albert’s mother and father, and Myrtle, Albert’s wife. |

|

Albert Shutt, the Performer |

|

|

Albert played the common fretted

instruments, beginning with the 5-string banjo, learning to first play by ear,

as his older brother had begun to do. Later,

he took formal lessons from local musician Howard Lawrence.

In the 1900s, Albert – then in

his twenties – organized and conducted several mandolin groups.

Later, in the ‘teens, he led three Hawaiian guitar bands and three

different banjo groups. Many of

these were said to use instruments of Shutt’s own design and manufacture.

Shutt himself played his new Mando-Bass-Harp-Guitar in at least one

Hawaiian group (see below). Albert closed the 1927 vaudeville season at the Novelty Theater with his 12-member “Banjo Jazz Band of Home Boys.” They were also the first musical group to broadcast over Radio Station WIBW from the Hotel Jayhawk (or Jayhawk Theater). His son Melvin was in this and several others of his father’s banjo groups, which, again, were often playing new instruments made by Albert. |

Shutt's Banjo Band, late 1920s. Albert is second from the right, his son Melvin second from the left. |

|

In addition to his performing, Albert taught hundreds of

pupils to play guitar, banjo, mandolin and violin.

He began this sixty year teaching career in the 1900s, leading many of

his students in public performances with his various groups. Three years before Albert’s at age 85, the Topeka

Capital-Journal wrote that he was “still active, full of ideas and plans, and

has entered a song in the Centennial competition.” |

|

| Albert Shutt, the Composer |

||

|

Albert published over two dozen works in his career, many of which were patriotic themed. His new arrangement of "Our National Anthem” featured a new melody for the “Star Spangled Banner” - an attempt to create a tune that people could actually sing. It was officially approved by the U.S. Congress in 1941, but unfortunately never caught on, other than seeing some local use. I am still looking for a copy of the sheet music, which features Shutt himself on the cover with his mando-bass-harp-guitar (more on this image below)! Other patriotic themed

compositions included “ Two of Shutt’s best-known

marches, “Allegiance” and “ He also wrote children’s tunes, with “Cat and Dog” becoming a popular square dance number, and “The Dog Show” recorded with Shutt’s own banjo accompaniment. |

|

| Albert Shutt, Inventor and Instrument Maker |

||

| Albert Shutt was an amazing

inventor, not to mention a very artistic designer as well.

Between 1906 and 1924, he patented at least nine different inventions or

designs for stringed instruments (some have proven difficult to find; there may

be others). Who

knows how many others he applied for and was never granted.

His designs and inventive modifications to existing instrument components

show a clear reaction to, and competition with, the Gibson company’s popular

features, although he did manage to beat them to a couple of key features. Shutt's

first

patent - in 1906 - was for an ingenious mechanical tuner which would attach to a

guitar or mandolin bridge and operate via calibrated reeds that would

sympathetically vibrate as the string reached the correct pitch.

I would love to find one of these – way

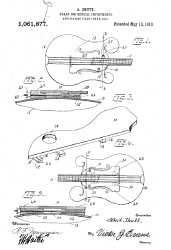

cooler than a digital tuner (and probably perfectly accurate)! Right: Next (1909/1910) came his first original mandolin design – with a vaguely Gibson-like “Florentine” shaped, carved top body. Most importantly, it was likely the first carved-top mandolin to include F-holes, preceding Gibson’s F-holes by many years. |

|

|

|

Left: A year and a half later in 1911, Shutt refined the mandolin body shape in his next design patent. In particular, note how the bass-side scroll more closely emulates Gibson's. 1912/1913 saw his new elevated pickguard (right). This was theoretically an improvement over Gibson’s, as it featured a small soundhole so as not to block off the F-hole, along with the option of having dual pickguards. It is shown on a slightly altered mandolin body - most likely a crude copy of the previous drawing for representational purposes, and not another design change. In

1914, Shutt developed his

fully-compensating bridge, which , again, challenged Gibson’s own compensating bridge. |

|

|

|

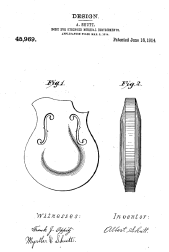

Left: 1914 saw a new mandolin design in an effort to offer a less expensive model. In removing the scrolls, Shutt created a distinctive new asymmetrical shape. At the same time, a very curious bit of history occurred. Shutt's patent is # D45969. At right is patent # D45968, which was issued on the same date as Shutt's (June 16, 1914). Yet this early F-hole mandolin design is credited to William Schultz (originally Wilhelm), the founder (1892) - and in 1914, still the president of - the Harmony Company. As the Harmony design also featured early F-holes, and a consecutive patent number, there is no doubt of a relationship - but what was it? There are many intriguing possible scenarios here. One is that independent Kansas maker Albert Shutt may have tried to solicit Chicago's largest instrument factory to make his mandolins. Then, instead, Schultz created a simpler F-hole instrument that his company could presumably produce more cheaply. The reverse scenario has also been proposed - that Shultz hired Shutt and his small staff to build better carved top and back mandolins for Harmony. More on this below under "The Shutt Instruments." |

|

|

Jack Shutt says that his grandfather started building instruments in 1910, “to supplement his income from teaching music.” His first mandolin design patent – applied for on December 9, 1909 – suggests that it was slightly earlier, certainly throughout 1909. By the time of the surviving catalog, Albert had created a full line of fully-formed instruments. Unfortunately, the catalog date is unknown - Albert's son, Melvin inscribed the catalog with the date "1912," but the patents seem to indicate that it was more likely 1914. Further research of the dates of these various unknown Cadenza ads will undoubtedly fine-tune the time period. These mandolins and guitars were clearly influenced by the

Gibson instruments, which by then had a virtual stranglehold on the market. Though

Shutt’s instruments were of equal quality and similarly distinctive, he simply

didn’t have a chance – even though, ironically, he scooped Gibson by adding

F-holes to his archtop instruments a decade or more before Lloyd Loar did. |

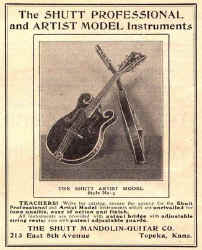

Cover of 1912-1914 Shutt catalog |

Cadenza ad, date unknown |

|

|

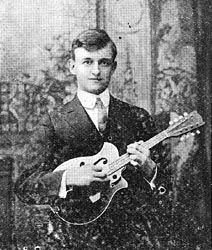

Ads in Cadenza magazine - the main trade publication for Shutt's potential audience - did little to earn Albert any orders, although the trio at left illustrates the instruments' visual, if not sales, appeal. At right, mandolin composer Warren Dean with a Shutt model A2. |

|

||

|

Cadenza ad, date unknown. Pictured are the Artist Model mandolin, mandola (?) and unique "Sub-Bass Guitar" (see below) |

Cadenza, June, 1914 | ||

Shutt designed the instruments himself and assembled them in his home. It is thought that he had expert violin makers helping - perhaps carving the tops and backs. No one knows how many people worked for him, nor how many instruments he made. Other than his inventions and prototypes, he filled orders only as they came in; later he supplied tenor banjos for his various groups. Jack’s father Melvin believed that Albert had made only about a hundred instruments total - most likely with the help of his workers. Though this seems a very low number, it does fit with the surviving instrument count, which is extremely low. There are no clear records, but

according to Jack, the Shutt business was always in Albert’s |

Shutt's Jackson flat building today |

||

|

1333 Kansas Ave, Topeka - Shutt's home and workplace for nearly forty years |

|||

| The Shutt Instruments

Jack Shutt mentions only one hundred Shutt instruments total – which would include many later tenor banjos and mandolin-banjos, and perhaps the more common mandolin model built for Harmony. However accurate this count is, it is obvious that the instruments never caught on - or rather, that they never had a chance, as they were all but obliterated by the Gibson merchandising juggernaut. I’ve heard of at most two dozen instruments – a few in the hands of Jack Shutt and collectors Lowell Levinger, Stu Cohen and Jim Reynolds (since dispersed), plus an occasional specimen here or there. Right: Jack Shutt's six

instruments built by his grandfather: |

|

| Those lucky enough to own a Shutt instrument praise them highly. David Grisman compares both the quality and tone favorably to pre-Loar Gibsons, as do collectors Lowell Levinger and Jim Reynolds. The latter adds, "I did set up one of both styles of mandolins. Oddly enough, the 2-point had a fuller sound; I attributed that to the fact that the scroll models had a solid dovetail block that included the two scrolls. The sides were not bent around the scrolls, but instead were joined at the beginning of the scroll, with a very slight seam showing on both sides. Of course the top and back wood covered the blocks and were bound with celluloid further hiding the fact. Both mandolins were well made and had no cracks or loose seams that are seen so often in Gibson instruments of the same time period." |

|

Click here for PDF

file of the full 1912-1914 Shutt catalog

|

| The Mando-Bass-Harp-Guitar | ||||

|

One of the most interesting and

impressive things about the Gibson harp guitars is the fact that they featured

fully carved tops and backs. Until

very recently, most guitar aficionados thought that they were the only

“archtop” harp guitar ever created. Lately

we have discovered specimens of an Almcrantz and Regal archtop as well, though

these appear to be pressed and molded archtops, rather than carved.

But we also now know that shortly after 1910, Albert Shutt – once again

nipping doggedly at the heels of Gibson – created his own carved top harp

guitar. And as in many of his

inventions, he did Gibson one better – by ingeniously combining Gibson’s

Mando-bass and Harp-Guitar into one! There

was simply nothing else like this instrument, before or since.

More impressively, Shutt’s acoustic version of a 4-string bass played

like a long-scale guitar is an amazing precursor to the revolutionary Fender

bass and today’s acoustic variants. Here’s how Shutt managed his

clever combo-instrument. There are ten sub-bass strings on Gibson’s standard harp guitar, providing (with the neck’s E and A strings) a full chromatic scale. Shutt realized that if he swapped the harp guitar sub-bass strings around, he could put the four notes of a mando-bass over a second fretted neck, and thus press these strings into double duty. They could now be played fretted as a mando-bass or played open as the floating bass strings of a harp guitar! The second neck is tuned exactly the same as Gibson’s 42"-scale mando-bass (EADG – an octave lower than the four lowest strings of a guitar) – but with a 30” scale. Inexplicably, the otherwise-ingenious Shutt seems to have made a miscalculation, as he only includes six more open sub-basses, for the same total of ten as the later Gibson. But he needed twelve, as unfortunately, two of the assigned mando-bass neck sub-basses are the very notes Gibson did away with when they reduced their harp guitar’s sub-basses from 12 to 10 (the E and A from the neck instead being used). Thus, Shutt is forced to omit two notes from the chromatic scale – choosing C# and D# (randomly?). While he is quite clear about the true pitch of the sub-basses over the mando-bass fretboard, Shutt is inexact in describing the accurate pitch (octave) of the remaining six sub-basses, stating only that they “are tuned in unison with the same tones made on the four Mando-Bass strings.” Clearly, these remaining notes can be fretted in either one of two octaves on the open E, A, D or G strings – so we are left with one of the following scenarios:

In either arrangement, the ten sub-basses are no longer linear, so this must

have been a brainteaser! The circa 1912 catalog pictures the M-B-H-G Style “0, No. 3”, which sold for $165. The listed Style “0, No. 2” – at $155 – is exactly the same, with less choice woods. A 16-string “Sub-Bass Guitar (Style “No. 3”)” is Shutt’s $140 version of Gibson’s harp-guitar, and may have had the same tuning of the ten sub-bass strings as Gibson's. Jim Reynolds pointed out to me that the catalog

instrument has what appears to be truss rod covers on both necks! Like much of Shutt's work, this is important news.

Jim adds, "In

the past I spoke with George Gruhn

about the truss rod covers and showed him (this image). He was mystified, thinking as we all do that is was a Gibson innovation circa

1922 or so. Shutt scoops Gibson again! |

||||

|

|

| This remarkable photograph appeared on the cover of Shutt's sheet music shown above. Albert is seen playing bass on his Mando-Bass-Harp-Guitar - which may be the very one shown in the catalog and the only one ever built. His Hawaiian quintet features three young ladies - possibly students of Albert's - playing what appear to be Knutsen steel guitars! | How wonderful to know that at least one performer ordered Shutt's "Sub-bass Guitar." For all we know, it may have sounded similar to, or perhaps even substantially better than, the Gibson Style U of the same era. With those F-holes, it may have packed even more punch. It also looks to be a little more comfortable size-wise and was about half the price of a Gibson. I find it inexplicable that Gibson sold several hundred harp guitars, while Shutt seems to have managed to sell only one (or extremely few). |

|

Here are the Shutt Mando-Bass-Harp-Guitar and Sub-Bass

Guitar compared.

If the player were not tilting his instrument back, my guess is that it would have basically the same outline and proportions of the catalog picture at left. Rather than two fretted necks and a third support post, the sub-bass guitar has a second, unfretted "support neck" with the end of the fingerboards appearing symmetrical. It looks like it has a large, centered, single tailpiece as opposed to the two separate tailpieces on the M-B-H-G. Only the M-B-H-G has the special pearl headstock inlay proclaiming "The Shutt." Both have F-holes in a carved top. This was the only harp guitar with this feature ever known until Mike Doolin created his jazz harp guitar in 2006. |

|

| There is no way to know how many

of either of these instruments were built, but as Shutt only built his catalog

instruments “to order” – and judging by the quantity of surviving mandolin

family instruments – we can surmise that is was undoubtedly extremely few.

Perhaps as few as the single examples shown in these images above: one

standard harp guitar and one mando-bass-harp-guitar.

To this day, no one in the Shutt family knows what became of this latter

instrument. I am certain that Albert

took special care of it, and, since he didn’t keep it, it may have been sold

to another player. I hold onto the

hope that it will one day be discovered, sitting in the proverbial closet. |

||

|

|

||

|

The catalog and family images were kindly supplied by Jack Shutt (right), the grandson of Albert. Some of this material is taken from a magazine article written by his father Melvin in 1977. Jack is a banker, not a musician, though he played trumpet throughout High School, with an instrument and lessons paid for by Albert. His father Melvin played banjo, guitar and mandolin like his father, often in the same groups. Special thanks to: Jack, Jim Reynolds (previous Shutt collector),

Lowell Levinger of Player's Vintage Instruments (a current Shutt collector), Arian Sheets, Curator of Stringed

|

| Updates

May, 2010: Added the Cadenza tone bar ad and the Acuff Collection G-3 guitar, thanks to Arian Sheets (reminding me I had the book on my shelf all this time...) |

|

If you enjoyed this article, or found it useful for research, please consider supporting Harpguitars.net so that this information will be available for others like you and to future generations. Thanks!

|

|

|

|

All Site Contents Copyright © Gregg Miner, 2004,2005,2006,2007,2008,2009,2010,2011. All Rights Reserved. Copyright and Fair Use of material and use of images: See Copyright and Fair Use policy. |