Luthier of the Month

|

|

|

|

by

Brad Hoyt |

|

November 15, 2005, The Office, Kent, England: It is late on a Tuesday afternoon and luthier Stephen Sedgwick is putting the finishing touches on a rosette. At first glance, his workshop, which he affably calls “The Office,” is like any other guitar maker’s workspace. Various materials and special tools for his profession are everywhere. However, upon closer inspection, I notice that the soundboard that he is currently applying the rosette to is much longer than what would be used for a conventional guitar. What does this mean? As I start counting the strings on one of his latest musical creations that I notice hanging on the back wall, it becomes clear - Stephen Sedgwick builds harp guitars! After taking a break from working on his current project, he was kind enough to answer some questions about his profession and his specialty, the harp guitar. |

|

|

Brad:

When did you first become interested in making your own musical

instruments and what kind of training did you go through in order to

become a luthier? Steve:

Well, I started playing the guitar at fourteen. This decision was

influenced by the fact that my older brother was playing bass at the

time. I knew I wanted a career in the music industry but wasn't sure

what area I should focus on. Before leaving school, I filled out

a questionnaire that was meant to help me determine what my interests

were and what kind of career I’d be inclined to be interested in. The

results that came back were Locksmith, Gunsmith, Piano Tuner and

Instrument Maker. The Instrument Maker stood out above everything so I

looked into it. After some consideration, I decided

to study luthierie at |

Stephen's 175 sq ft workshop |

|

I was taught instrument making by classical guitar maker David Rouse. Later, I would be taught by David Whiteman. They also taught me a lot about repair and restoration. Dave King is now currently the lecturer for guitar making. I also had an opportunity to study many other useful subjects whilst at Guildhall. There was Material Science, which involved wood biology, cell structure and growth, along with chemistry, which was useful for understanding glues and finishes. That information is important for restoration work. Acoustics was one of the most important classes; we covered a lot, including Physical Acoustics. I also took a French Polishing class, which was a special class that was part of the furniture department. |

|

|

The Scales Tunings and Temperaments class was very intriguing. The subject matter involved a lot of Indian music. Part of the work required me to make a classical guitar with “Pythagoras tuning.” It was a mind-numbingly difficult subject. Some other notable classes I took were Instrument

History and Instrument Design which was taught by the late great Dr

Terrence Pamplin, Music Theory, Business Studies

- which in theory made sense but certainly not easy to put it into

practice - and World Music,

taught by Jon Banks, an amazing musician. As you can see,

there were a good number of classes. I think that my time at Guildhall

gave me some good grounding - and certainly more knowledge gives you

more freedom. We had a wonderful library with many music and instrument

books. I also remember that there was a good mixture of French, German

and Scottish students in the instrument-making courses. Whilst at the

University, I got a part time job working at the local music shop. When

I started working there, I worked mostly in retail before eventually

spending most of the time in the workshop repairing guitars. The shop

catered to schools mainly, and also specialized in violin repair. I

worked there for about four and a half years before leaving to

concentrate on my own work. I still see the guys there from time to time

and they keep asking for a harp guitar (laughs). |

Sedgwick “Pythagoras Guitar” |

|

Brad:

Who or what do you consider to be your main creative influences? Steve: A lot of my influences come from other instruments. A great example is my 'Broken Heart' harp guitar. Many people love the Gibson harp guitars but they are too big and clumsy. Like Hendrix's version of Bob Dylan's 'All Along the Watch Tower', I took the essence of the Gibson design and made it my own. You can see the Gibson influence but my harp guitar is nothing like a Gibson. Mine has a flat top, different sound holes and much closer to a jumbo size guitar. It’s a much more modern design. It is easier to go commercial and build Martin guitars and Dyer harp guitar copies because of their great design. But it is much more difficult and rewarding to make your own way in life. The same goes for musicians and their music. I very much admire people like Mike Doolin for stamping out their unique design. I prefer to do original work rather than copy other makers. As regards to luthiers, Fred Carlson has been a hero of mine for many years. After seeing his work in American Lutherie and reading about him, I saw something magical about the guy and his work. It was an honor to meet him at the first Harp Guitar Gathering and his dedication to his work and new creations are a continuing inspiration. I’ve also been inspired by Linda Manzer's work, mostly because she made the Picasso and I saw Bruce Cockburn in concert with one of her guitars. She’s truly an amazing maker and her work has got me thinking about making arch top guitars. Then there’s British maker Andy Manson, who’s famous for making the triple neck for John Paul Jones. His book 'Talking Wood' is fantastic and I recommend it highly. I would like to make a triple neck for myself some day. As for classical guitars, I’d also

like to mention my lecturers David Whiteman and David Rouse, who used to

bring in a guitar every once in a while to show the class. Those

instruments were breathtaking and perfect in every possible way -

perfection both in craftsmanship and in sound. Jeffrey

Elliott

is another big influence in a similar way. The harp guitar he designed

with John Sullivan for John Doan sounds amazing and is a landmark in

instrument design and, historically, it is one of the most important

harp guitars to date. I feel fortunate to have met him briefly. Last but

not least, it must be said that the most beautiful and sexiest classical

guitars are made by British maker Paul

Fischer. |

Sedgwick

Broken Heart Harp Guitar |

|

Fred

Carlson and Stephen Sedgwick |

|

Harp guitar under construction |

Brad:

Can you recall your first exposure to the harp guitar? Steve:

The earliest recollection that made me think about harp guitars was

seeing Torres' SE83 11-string classical guitar in Jose Romanillos's book

‘Antonio de Torres Guitar Maker - His Life & Work.’ Brad:

How is making a harp guitar different from making a standard

guitar? Steve: They take a long time to make. Especially when making the ones with the extra acoustic arm section. There is so much more work involved. There is enough material in the arm section to make a mandolin. The arm section has extra joints, bindings and purflings. There’s more wood to sand and polish and there’s also the cost of six more tuners and the time of setting those up. Harp guitars usually have a second smaller sound hole and rosette in arm section. You can hide the ends of the normal rosette under the fingerboard but there is nowhere to hide these ends on the smaller harp arm rosette. The harp arm rosette is completely exposed. Obtaining the wood needed for harp guitars is not easy because it usually has to be specially cut. On my harp guitars, there is about 140 pounds more tension on the soundboard than a regular guitar top and thus the bracing has to be adjusted. There’s also the issue of finding that fine line where the instrument is neither over-built nor under-built. You usually have to get a custom-made case and/or a padded case. Also, the pickup arrangement can be a nightmare because there are so many possibilities. |

|

Completed Harp Guitar |

|

|

Brad: What can you tell us about your take on the harp guitar? What makes the Sedgwick harp guitar unique? Steve: My standard harp guitars with the extra acoustic arm are probably among the smallest harp guitars out there. No one has asked me to build a bigger one. I had only seen one Gibson harp guitar in the flesh before going to the Harp Guitar Gathering. So I wasn't too sure what size to make a harp guitar. It made sense to have a regular guitar with the extra acoustic arm. A lot of people have commented that they like the fact that it is smaller and the fact that the design also works. The lower bout width is 15” where as the 'Broken Heart' is like a small jumbo with a 16” width. As regards to the sound, I'm very modest so it’s difficult for me to say. Acoustically they are very well balanced. A recent customer and his wife, who is also a musician, told me how clear and responsive they thought their new instrument was. For the 'cut-throat' price I charge, I think that I make the best harp guitars on the planet. And it’s not only me saying this, but other people have commented that my harp guitars are better sounding than some harp guitars that are twice the price. |

|

|

Brad:

Can you tell us about the other harp guitars or harp guitar-like

instruments that you’ve made? Steve: The earliest harp guitar I made was a copy of Torres's SE83. A beautiful classical guitar in it's own right, but I would like to make another at some point with the knowledge and experience I have gained since. Then there was the 21-string harp guitar (7 bass, 6 guitar, 8 trebles) that I finished in early 2005 and an 18-string guitar (6 bass, 6 guitar, 6 trebles) for my friend Matthew Draper. He had a lot of say in the design and look of the instruments - which I don't mind, because you get what you really want, and it takes me to new places. The one drawback is that with so much customer input, the time to make the instrument could double or quadruple and the cost could go up significantly. You can really see the effect of Matthew’s input when you put the 21-string and 18-string next to one another. You would think they were from two different makers. |

Reproduction of

Torres SE83 11-string classical guitar,

built by Stephen Sedgwick |

Sedgwick

21-String Harp Guitar |

Sedgwick 18-String Harp Guitar collaboration with Matthew Draper |

|

The harp mandolin was

inspired by Gregg's Knutsen harp mandolins. I love mandolins and so I

managed to get around to making a harp version. As you know, the

instrument has a side port hole, which really opens the sound up. It was the first side port hole I have done and I

will be doing it again at some point. Brad: Can you tell us anything about what you are currently working on? Steve:

Well, I’m working on something now that’s rather unique. You should

know, Brad, since this is your instrument! I'm also finishing off a

'Broken Heart' harp guitar, which has a beautiful mother of pearl vine

on the fingerboard. That instrument will be going off to a shop called Guitar

Works Custom Shop in |

Sedgwick

Harp Mandolin with port hole |

Unfinished Broken Heart |

|

|

Brad:

Sounds like you’re a busy man - and since time is money, I think

it’s time for me to let you get back to work! Thanks for taking the

time to share your experiences with us. Steve: Thanks for stopping by! For more information about Stephen Sedgwick and the instruments he makes, visit his website at www.stephensedgwick.co.uk ! |

Continue to Part Two of Brad's series on Stephen Sedgwick, which introduces the mystery instrument! |

|

|

| About the Author | |

|

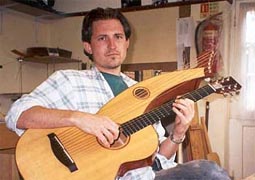

Brad Hoyt playing a Sedgwick harp mandolin |

Brad Hoyt (www.bradhoyt.com) is a composer, pianist and harp guitarist who has performed and recorded extensively in America and Europe. Brad graduated from Ball State University with a Bachelors degree in Telecommunications and an associate's degree in Jazz/Commercial Music. Part of his studies included classical guitar lessons and private piano lessons with renowned jazz pianist Frank Puzzulo. Also while attending Ball State, he preformed with the school's big bands, small jazz groups and with his own rhythm and blues band. After graduation, he moved to New York City and performed regularly as a solo pianist and ensemble musician. While living there, he arranged an original piece for chorus and orchestra and his original Christmas arrangements were aired nationally on NBC. Between 1999 and 2002, Brad recorded and performed regularly in Europe. Today, Brad works at Steinberg, the recording software division of Yamaha Corporation, and lives in Carmel, Indiana with his wife Andrea Hoyt and their children Loreena and Luke. Brad is currently working on a new duet album of original material featuring himself on piano with various harp guitarists. |

|

If you enjoyed this page, or found it useful for research, please consider supporting Harpguitars.net so that this information will be available for others like you and to future generations. Thanks! |

|

|

|

All Site Contents Copyright © Gregg Miner, 2004,2005,2006,2007,2008. All Rights Reserved. Copyright and Fair Use of material and use of images: See Copyright and Fair Use policy. |