Of course, “custom” applies to nearly all Bohmann harp guitars!

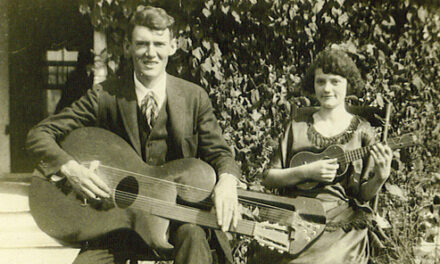

This specimen recently came to my attention via the original owner’s descendants. It has been in their family for several generations, commissioned by a great-grandfather, whose last name was Linscott – engraved in the 3rd fret marker.

The family hasn’t been able to discover the details of their harp guitar-playing ancestor, saying, “We have very little information about the original owner. We do know his last name was Linscott, which is also etched in the mother of pearl inlay on the neck. His first name may have been William, and he had a son named Elbert William Linscott (known as Scotty), who was also a musician. He may have also played banjo, and played in some capacity as a professional musician or in a band or orchestra of some type. He may have lived on the east coast in the New York area, possibly Long Island.”

And what of the instrument?

Most noticeable are the irresistible “Mutt and Jeff” headstocks.

The main headstock is certainly eye-catching, as it is extended another 2/3 in length to accommodate 10 strings on the neck. Bohmann stacks up his then-standard tuners by fitting a second partial set against the standard set. Pretty wild! The tuner markings are unusual in that they appear identical (with the one set cut down), yet have two different patent stamps – one for his 1890 patent # 427,962 (which these tuners probably resemble), and one for a previously unknown 1891 patent # 464,912, that has nothing whatsoever to do with theses tuners – it applies to a 5th string banjo tuner (inexplicably titled “Tuning Peg For Violins)!

The 10-strings are in the standard 6 courses, with the low 4 doubled as in a 12-string guitar. This was a new, but not uncommon, occurrence around 1900 – something I’m currently in the midst of researching for another upcoming piece.

The 9-string sub-bass headstock is unusual, but something we’ve seen before – on this unfinished instrument from the Bohmann factory find in the 1970s (above), and Bohmann’s own instrument below.

The old factory instrument was probably a work-in-progress pre -1900 instrument, but has the later “tone rods” (not strings, but stiff, pitched metal rods) – either Bohmann experimented with them well before his 1915 patent for them, or he or his son was later doing a retro-fit on this earlier instrument. Note that it has Bohmann’s impressive pre- 1896 sunburst finish (when is someone going to write the History of Sunburst Finish? – I bet this could be one of the first).

The present instrument doesn’t have a sunburst. It dates to post-1900, due to the presence of all Bohmann awards granted – up to 1900 – on the label.

Note that while the bridge does curve down to help the scale length of the 9 subs, it is too little, too late – the non-linear placement of the two necks ensures that the bass neck is even shorter than his standard double-neck design, where they are equal. This bridge is a real cool, early pinless design, intended for ball end steel strings (the metal support is not original). I believe this was used from around 1890 into the 1900s. I was able to see this in action on the similar 8-bass instrument I briefly had (and foolishly sold). Mine had 2 alignment screws for each string, this has one. The screws (on mine) serve as adjustments for individual string height, but also go through the top (with no extra bridge plate underneath) – so the advantage of not weakening the top by drilling holes for all the pins is somewhat lost.

Note that Bohmann’s pictured specimen and the ex-factory specimen are very close in appearance, and both very symmetrical.

Linscott’s may have been started out to be similar, but ended up very different, with both necks quite askew. Was this a “mistake” by Bohmann, or a deliberate placement for some desired result of either his or Linscott’s? While the main neck is aligned perfectly with the bridge, the body appears to exist in its own rotational orbit. Or is it vice versa? The bass neck then ended up as it did by default.

The long metal bridge support is an add-on, and there are no indications of any internal tone rods (as expected).

The fancy back binding and purfling are unusual for Bohmann. It looks like nice Brazilian rosewood back and sides, likely laminated as in my 8-bass early 1890’s instrument.

Interesting that Bohmann’s aesthetic regarding neck inlays runs from the exquisite to the sloppily gaudy. I’ll let you decide where this one lies. No doubt Linscott loved it! And judging from the playing wear, he definitely loved this undoubtedly wonderful-sounding harp guitar as well.

The family is interested in finding a good home for their historical treasure; feel free to contact me with any offers.

Note: As always, with anything Bohmann – thanks to Bruce Hammond for all his research and analytical help.