Continuing Saturday’s story on Joe and Linda Morgan’s visit to the Martin factory (photos are theirs)…

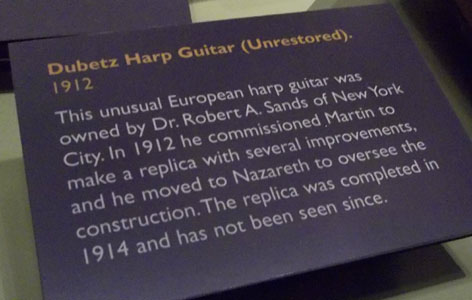

I imagine that the public must invariably be surprised (shocked, more likely) by the strange harp guitar displayed with all the normal Martin 6-strings. It was originally shown in a curious 1-page story on page 214 of the original 1987 Martin book by the late Mike Longsworth and is an intriguing part of both Martin lore and harp guitar lore. Apparently, one Dr. Robert Sands shipped his “Dubetz model harp guitar” to the Martin factory in October 1912 to have them build him an improved reproduction. Longsworth’s information came from correspondence letters between Sands and Frank H. Martin that were found with the surviving original instrument, stored for decades in Martin’s North Street plant’s attic. The pieced-together information (which does not appear fully accurate) tells how Dubetz himself (?) sold the instrument to Dr. Sands, sometime “after 1890.”

Dubez has been in my Encyclopedia of Harp Guitar Players of the Past from the beginning but was always a somewhat cryptic figure. As I have only perfunctorily investigated him, let me explore him, and especially his harp guitars, a bit more now. Much more is now known about Dubez, thanks to his recent biographer, Michael Sieberichs-Nau, with whom I’ve corresponded over the years. His English “rough draft” of Dubez is currently online here.

Born in Vienna in 1828, Johann Dubez (or Dubetz) came from a successful musical family and was not only a virtuoso guitarist/composer, but a major figure on several instruments. His first instruments were the violin and guitar (he studied guitar with J.K. Mertz), and he performed publicly on each by his twenties. He would use both instruments in his career throughout his life. As the guitar’s popularity waned, he became a harp virtuoso as well, and later an important zither player. In an unusual move (instigated by fellow guitarist Regondi), he also played the English concertina. Yet another instrument was played by Dubez in his first solo concert in 1847: a “newly constructed guitar called the Guittaron,” which had “a slightly more marked tone than the ordinary guitar.” Michael and I are again brainstorming on whether this might have been some form of harp guitar (my suspicion), or (as Michael reasons) the Guitarion, a rare 1831 guitar invention by one Maximilian Franck that could be plucked or bowed.

The Martin entry mentions the Sultan of Turkey, who was among Dubez’s most notable patrons as he toured the Ottoman Empire in the final decade of his career. The “Milan” mentioned, who owned this harp guitar before Dr. Sands, was the nephew of Prince Obrenovic and became King of Serbia shortly later.

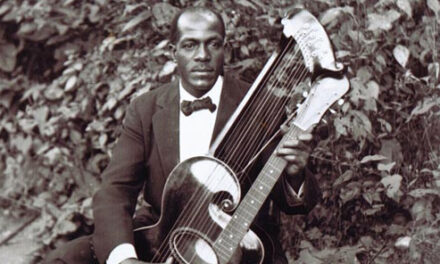

There are only two published pieces by Dubez (Michael prepared this one for Chanterelle) and many handwritten manuscripts in various collections. Michael tells me that most include bass notes that indicate that they were written for a harp guitar with up to 10 strings. His article also includes a quote about a nine-string guitar “invention” by Dubez. Besides the Martin Museum instrument, there is another 10-string harp-guitar (with a major cutaway) signed by Dubez in 1889 in Brigitte Zaczek’s collection. It’s not known who built it (or when), nor if it was Dubez’s own (though entirely likely).

Dubez died in May 1891, so must have sold Dr. Sands his harp guitar in the last year of his life. The photo in the Martin book obscured the number of bass strings, but Joe’s new photos show them to number 4 (for a 10-string [harp] guitar). In the book, Longsworth makes curious mention that “the original European-made Dubetz guitars were 5 in all. Mr. Dubetz had them made for himself over a number of years.” This information presumably came from Dr. Sands’ letters, as theoretically told to him by Dubez. We’ll probably never know how accurate this is, or what the “5” instruments were (could Zaczek’s instrument have been one of these?); so what we’re concerned with is Martin’s extant “European-made Dubetz guitar.” Apparently, no one had been able to decipher the model, nor even the label, on what we can today clearly recognize as a Friedrich Schenk “lyra-guitarre.” Joe’s photo captured just enough to confirm Schenk’s name on the label, which would have been visible through the soundhole in the headstock:

It is certainly believable that Dubez (based in Vienna) indeed ordered such an instrument (or several) from Schenk. This would have likely been in the 1840s, however, not c. 1870, as stated in the Martin book (scholar Alex Timmermann attributes Schenk’s dates as c.1800-c.1865). (Hmm…could this very instrument have been the mysterious “Guitarron”…?)

According to their records, Martin built Dr. Sands’ copy in 1914. The requested improvements included more room for the wrist and “thumb action on the neck up to the 17th fret” (that’s some serious thumb playing!), and “as many strings as practical to the harp portion, 16 more if possible”! (I would love to know how many they managed to fit!)

I can’t believe this instrument has never turned up in all these years – it’s a Martin “Schenk-copy,” for cryin’ out loud! And the company doesn’t seem to have noticed the coincidence/irony of the Martin-Schenk connection (they were both Stauffer disciples). Still, it’s cool that they kept the original instrument for a hundred years, and a nice touch to show us the separate back as well.

Proving once again the timeless and international nature of the ubiquitous harp guitar!

What a piece! And yes me too I would love to see the 1914’s version…

Benoit