Frank E. Coulter, as you may remember from my two previous blogs on the subject, was an obscure luthier who made a distinctive series of mandolins, guitars and harp guitars in Portland, Oregon in the 1910s-1920s. I’d like to now present some new discoveries and updates.

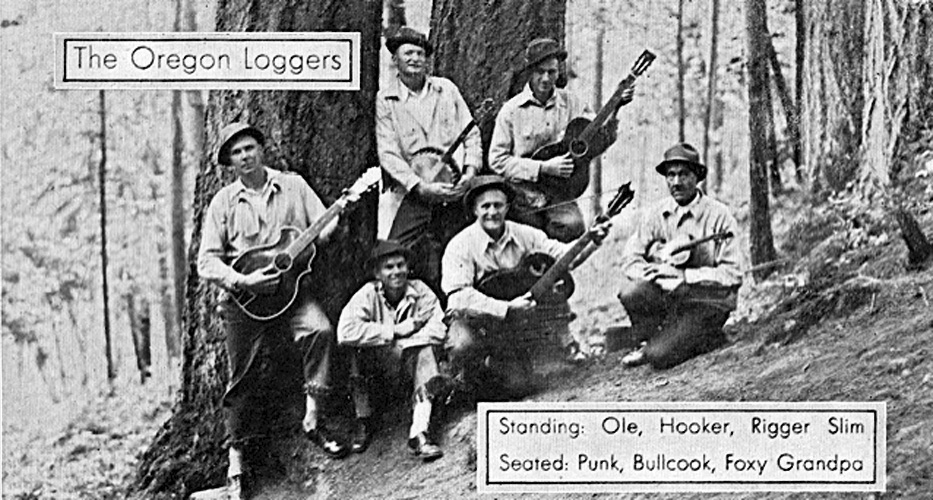

John Doan recently found this great photo of “The Oregon Loggers,” featuring a Coulter guitar played by group member “Bullcook” (now there’s a stage name!).

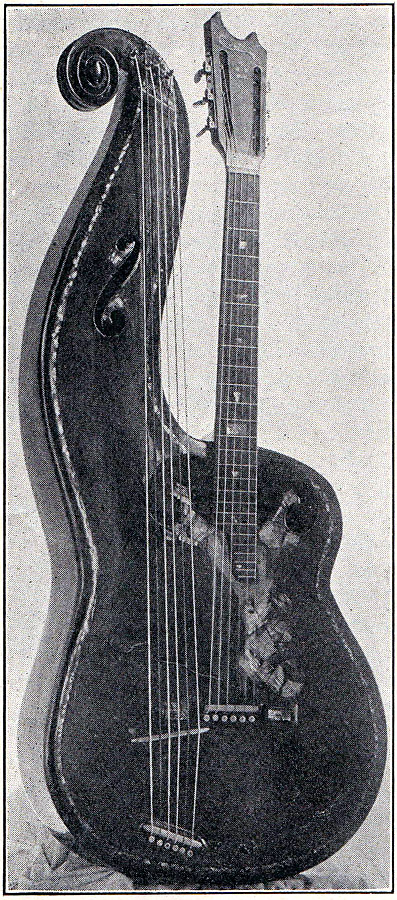

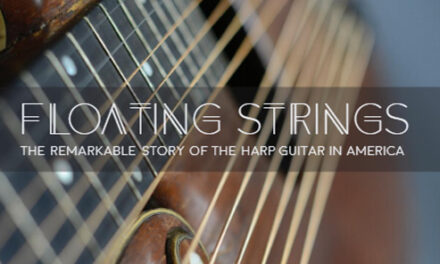

Next up is to report that restoration of the black-top, 12-on-the-neck eBay harp guitar is complete! Refer to this past Coulter blog to refresh your memory on this instrument. Though it was certainly a rare and interesting harp guitar, it was not something I wanted to take on. The lucky auction winner and brave individual was John Riley, from Newnan, GA, who had previously acquired and restored both a Wishnevsky and a Gibson harp guitar.

John shared his experience “real-time” on our old Forum, and completed the project recently. Here is the final result:

No, he chose not to address the finish…

John provides these specs and comments:

“The Coulter is 42” long, with a 17” lower bout and a body thickness of 4”. The scale of the neck is 24.75”. This compares pretty well to my Gibson (45” x 19” x 3.5”, same neck scale). The big difference is weight! The Coulter weighs a scant 7 lbs, as opposed to 12 lbs. for the Gibson!” John also describes it as “loud!”

John Riley also contacted a great-granddaughter of Coulter, Jane Sanford Harrison, who wrote, “My great-grandfather was quite a character, by all reports (he died a year after I was born) – extremely opinionated, and apparently very individual in the way he built instruments.” Because of John’s queries, she went digging in the family archives and found this remarkable Coulter heirloom – an original brochure! Thanks to Jane for kindly sharing this important document with us.

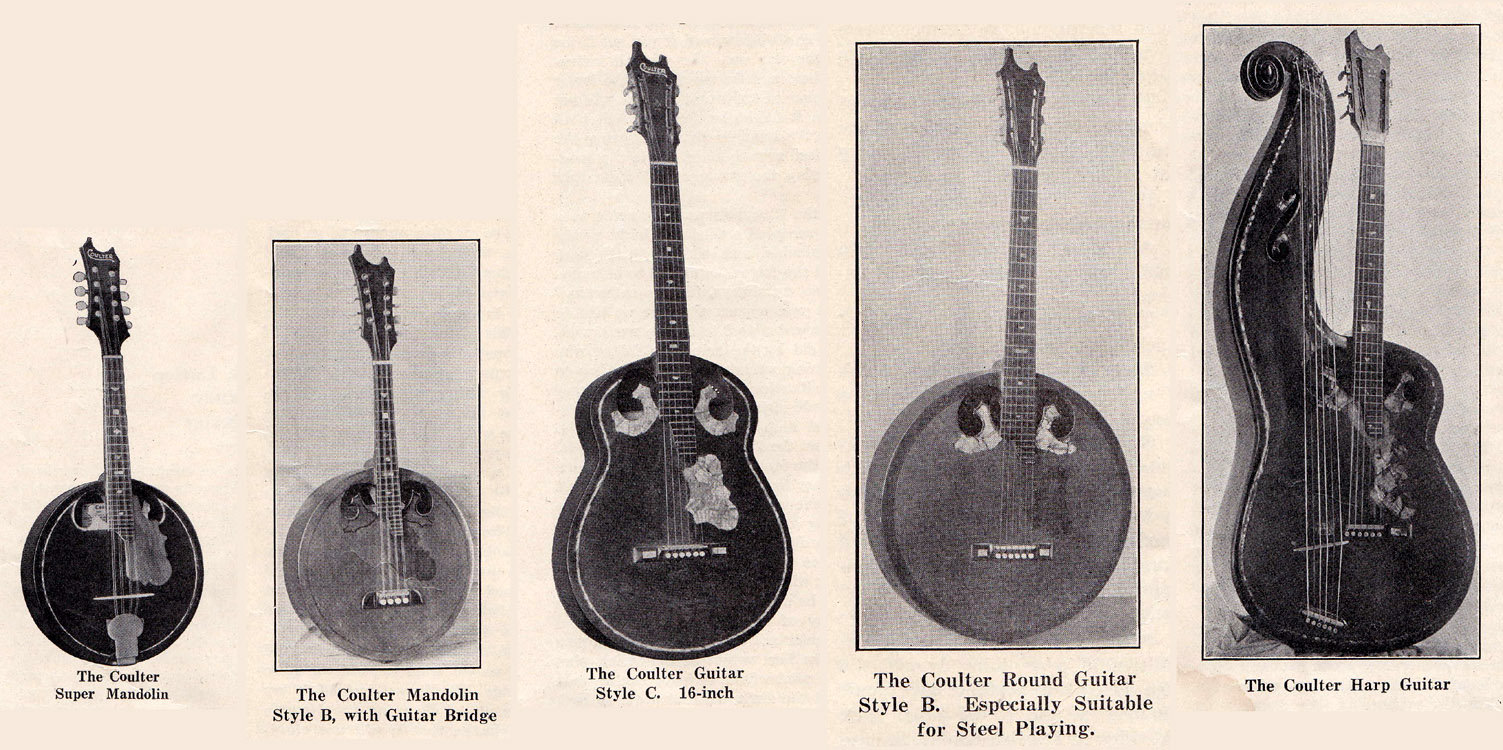

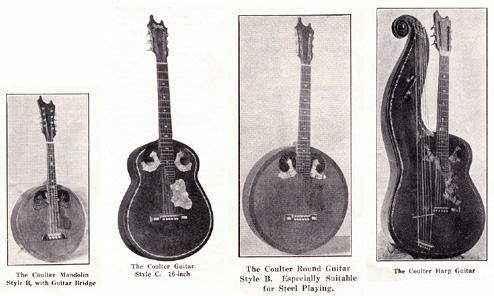

The most interesting historical finding in the undated 8-page catalog may well be Coulter’s own introduction to the whys and wherefores of his unusual construction techniques. He is not lacking in self-confidence! Next, we see all of his “standard” models, including the harp guitar – this one a dark-ish top with a 6-string neck and 6 sub-basses. Here is the complete line-up of illustrated instruments:

Note the perfectly circular shape of his mandolins and Style B guitar and the opposing off-center soundholes at the soundboard’s top. These represent some of his key “improvements.”

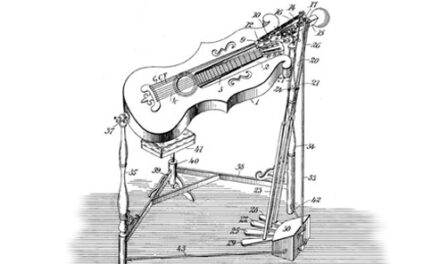

His catalog harp guitar generally matches John Riley’s instrument above, including Coulter’s specific arrangement of the bass strings, which have an individual pin “bridge” close to the rim (but just far enough away to rip out of the soundboard!) and then pass over a separate saddle. He mentions “six to twelve contra bass strings,” implying that he knows that that’s how harp guitars were typically configured and that he offers the same (one of his three known HGs – John Riley’s, seen above – has 7 subs).

At the close, Coulter shares his motto, which concerns “great instruments (being the) “product of great loves and the individual efforts of passion-driven men” (kinda describes my own obsessions). Like Chris Knutsen, he was an eccentric after my own heart!

Before examining our final eccentric Coulter discovery, I’ll point out a few pertinent catalog observations. He offers a very specific set of mandolin family instruments; in fact, he is one of the very few to list the entire set. Besides mandolin (or his “Super Mandolin”), he lists Piccolo, Tenor Mandola, Octave Mandola, ‘Cello Mandola and a “Double Mandola Bass.” Most have scale length listed, along with body diameter and depth.

From the catalog, we can also now see that Coulter specifically built three body sizes of the same 14” scale mandolin for different tonal characteristics: 10”, 11”, or 12”. That would explain why different specimens seem to appear so differently proportioned:

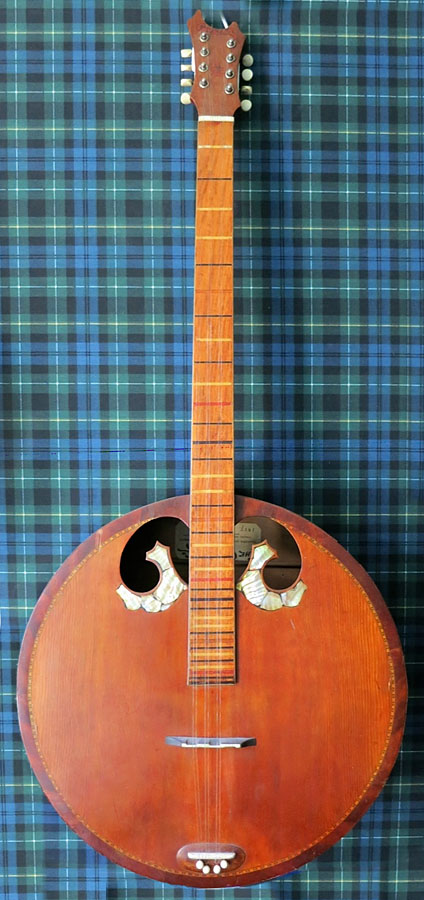

Which brings us to the present instrument, owned by John Doan, which by all appearances seems to be a fretless super-mandocello! I saw this ages ago at John’s home and didn’t pay enough attention to it (it’s subsequently been at his university office). He just now kindly photographed and measured it for us.

Though it has flush frets, it doesn’t appear to be meant for slide-playing, as it has a standard nut (and who would put double courses on a steel-played instrument, anyway? Well…me [the Miner-cello], but that’s a different story).

So John and I are thinking that it must be some crazy custom order “fretless mandocello.” Except that Coulter’s standard ‘cello is listed with a 24” scale (roughly standard for the time), and this one is 29”! Nor is it a “double mandola bass” scale, which was a full 44”. Any other guesses? Coulter specifies his catalog ‘cello as 4” deep with either a 16” or 18” circular body.

The above example, from Mandolin Café, appears to be (or started off as) a standard ‘cello with a seemingly much smaller body. John’s conforms exactly to the larger mandocello size. Whatever musical effects the player was after, they must have needed and asked for the inlaid fret markers, noticeable in all their multi-colored glory!

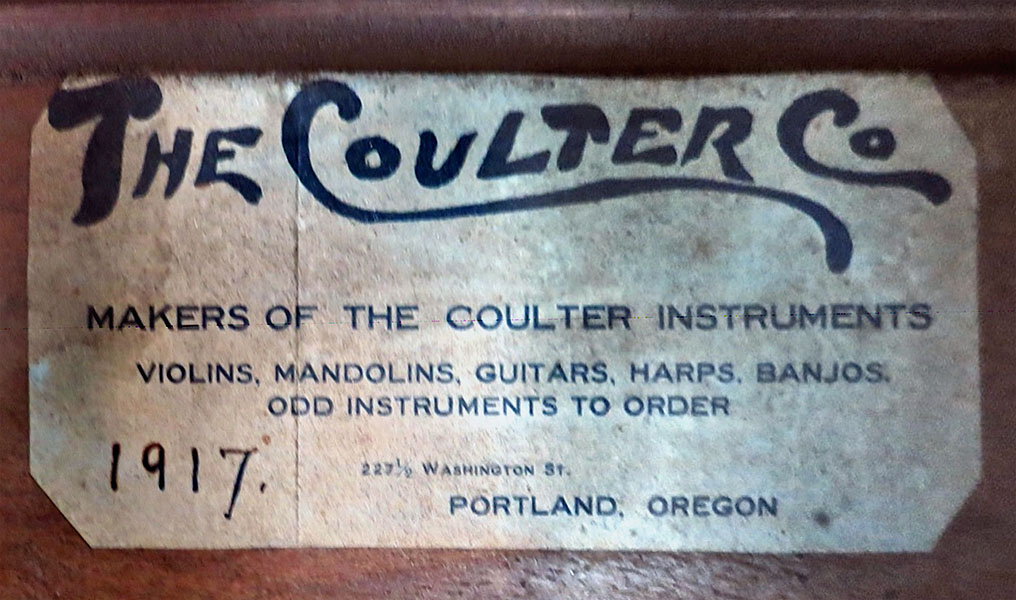

Also nice is the original 1917 label (Coulter’s standard label), of which this is our best image. Note how it clearly broadcasts Coulter’s passion in the final line: “Odd instruments to order.”

The fretless super-mandocello would certainly qualify!

Great article, Gregg! I’ve been looking forward to it. Thanks again for all of the help and encouragement you’ve given me in my projects.