Following up on Knutsen Nature Boy, Part 1 and our in-depth expose (Was William Pester, the “Hermit of Palm Springs,” the real “Nature Boy”? The answer may surprise you!), we’re now going to investigate the equally mysterious Hawaiian acoustic steel guitars that Pester was photographed with.

Please be forewarned that this will be a somewhat detailed and lengthy study (4000+ words…there I go again). In the parlance of my world, I’m going to seriously “geek out” here. Also note that I’ve already begun editing this article based on feedback – I hope to get much more! I’ll put updates in red.

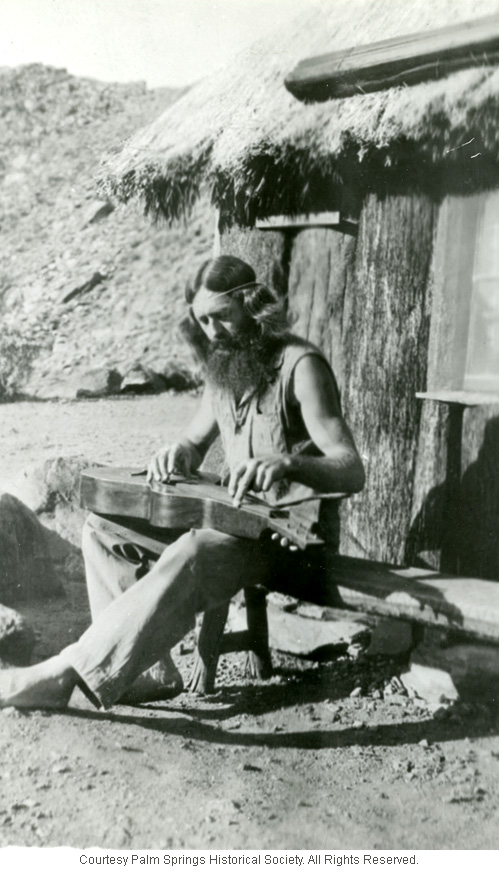

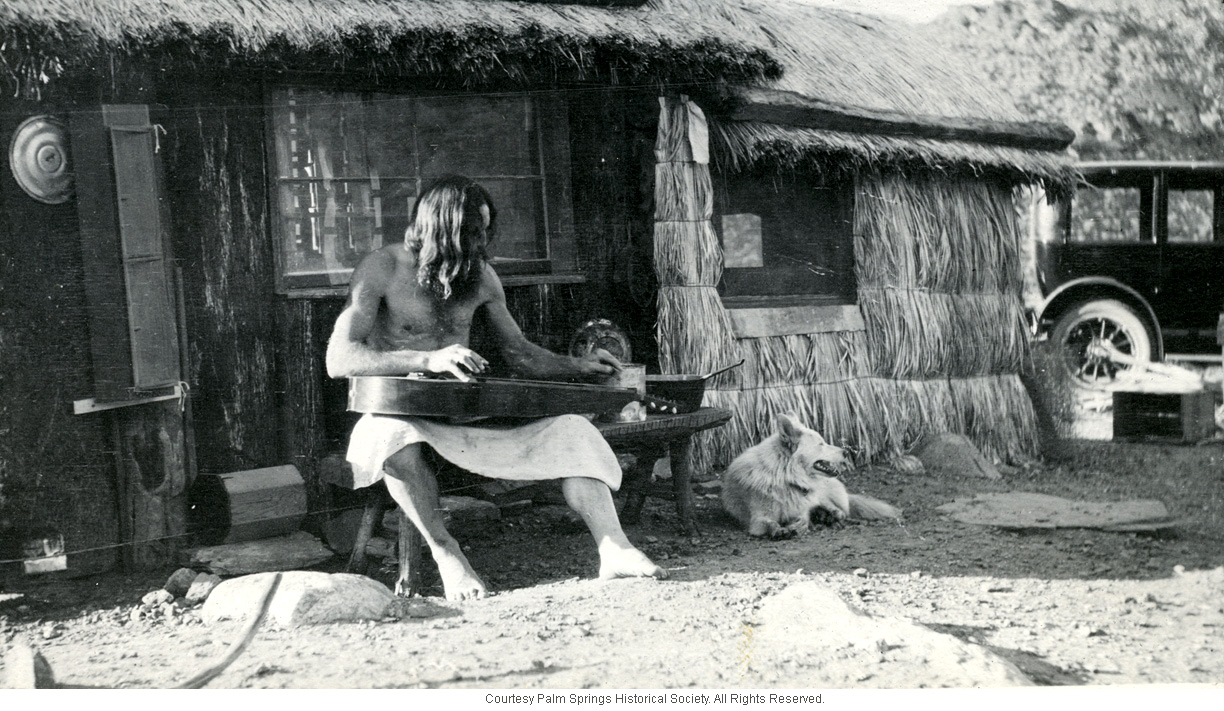

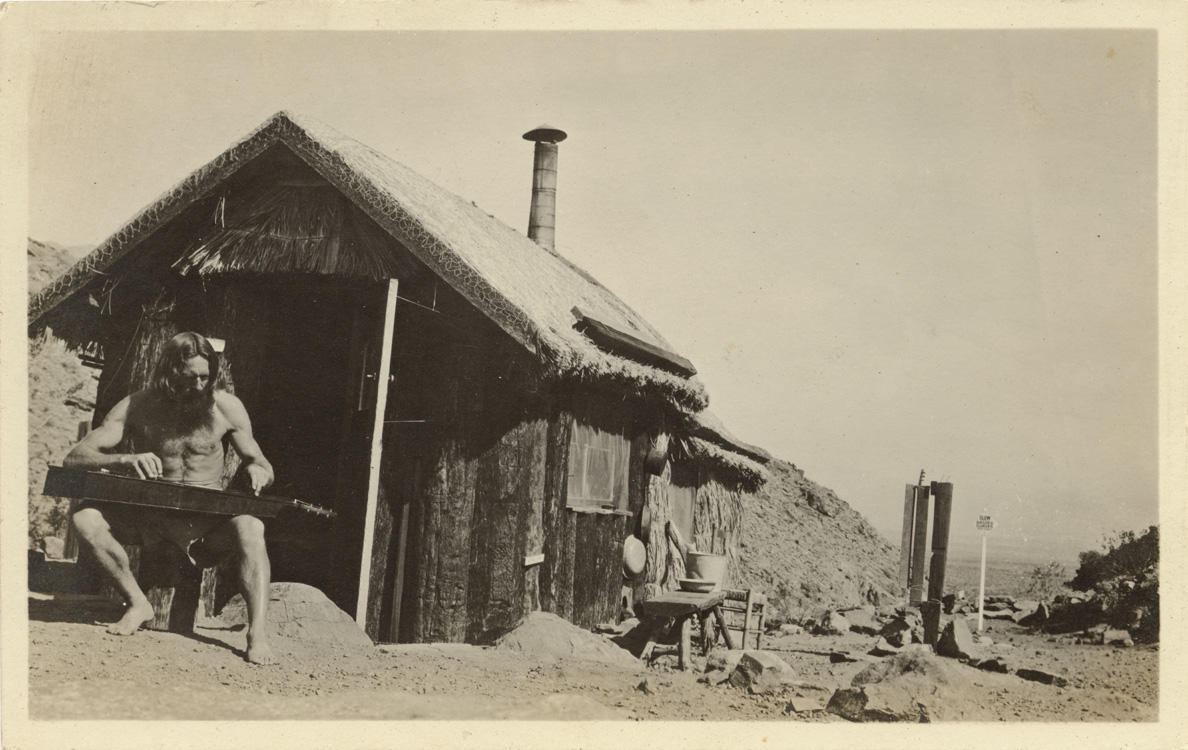

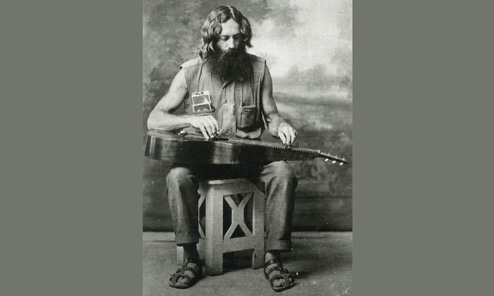

It was back in 2002 that I saw my very first Pester image – a fuzzy copy forwarded by my Weissenborn/Knutsen collector pal Ben Elder. The image shown here is the first time it’s being published showing decent resolution of the guitar.

This, along with the majority of new images below, were kindly provided and licensed by the Palm Springs Historical Society (“PSHS”) for this new study.

After announcing the discovery on his public radio program (Ben may be a bigger guitar geek than I), a listener sent Ben two more Xeroxes of Pester images from a book about Palm Springs history. Through the author, Palm Springs mayor Frank Bogart, I tracked down the book and with his permission posted the images and captions on The Knutsen Archives. Even better, I was able to add Pester’s instrument to the Archives with its own unique Inventory Number (HW19) as it definitely appeared to be a Knutsen steel guitar.

Eventually, I acquired my own original postcard of the best and most familiar image which provided better instrument details (inset, left). Yeah, sure seems to be a Knutsen, though it remains a tricky call. Even to this day, Ben Elder remains uncommitted, saying “…in truth, I’m no closer to a verdict on the mystery guitar than when we first saw the Pester images.” Weissenborn/Knutsen Tom Noe, however fully supports the conclusion, and recently weighed in on all my following bullets. The identifying features include:

- The bridge, which looks like the “bow tie” shape that Knutsen used and Weissenborn duplicated for his early guitars. Tom says, “Knutsen used the ‘bow-tie’ bridge beginning in 1909 and continuing until he adopted the ‘smiley’ or ‘wienie’ bridge after he arrived in L.A. Weissenborn began using the Knutsen bow-tie bridge on his first steels and refined it into his bat-wing by eliminating the concave line along the top of the bridge.”

- The headstock shape, which looks more like an early Weissenborn; Knutsen’s were rarely this petite and symmetrical, though there are a few.

- The deep body, a classic Knutsen configuration. Tom says, “In that mid-teen time frame, Schireson brothers were manufacturing steels, but all of theirs that I have seen – the Mai-Kais and Lyrics – are all thin bodies, 2 to 2-1/2 inches body depth. Oscar Schmidt didn’t start manufacturing Hilos until after the ‘second wave of Hawaiian music popularity,’ which, according to Music Trade Review, began in 1922. So it can’t be those.”

- The fancy/gaudy fingerboard inlays – typical Knutsen, though Weissenborn’s earliest instruments played around with the inlays a lot more.

- The solid, light-colored binding on top and back, likely a blonde wood Knutsen typically used for his non-rope models. Tom says, “Knutsen made heavy use of maple for bindings, and his use of maple began in Tacoma on harp guitars and continued for years thereafter, including his time in Los Angeles. So I would say that what we are seeing is maple. Except for rope binding, which was holly/mahogany, Weissenborn generally did not use wood strips for binding.”

- The extra-long fingerboard extension – for me, though, the “smoking gun” – something seen on random Knutsen steels, but never to this extent on any other maker’s Hawaiian guitars of the period to my knowledge. Tom says, “The long finger extending from the fretboard is pure Knutsen. I may have seen it elsewhere, but I cannot recall it.”

Taken one by one, the features above can point to different things, but the total combined features and appearance virtually scream “Knutsen,” exhibiting his aesthetic rather than Weissenborn’s or others’ of the era. This photo remains the best image of Pester’s steel guitar to this day. For our study, we’ll refer to this c.1917 image as “key.” P.S: Note Pester’s fingerpicks that can occasionally by seen in photos of him.

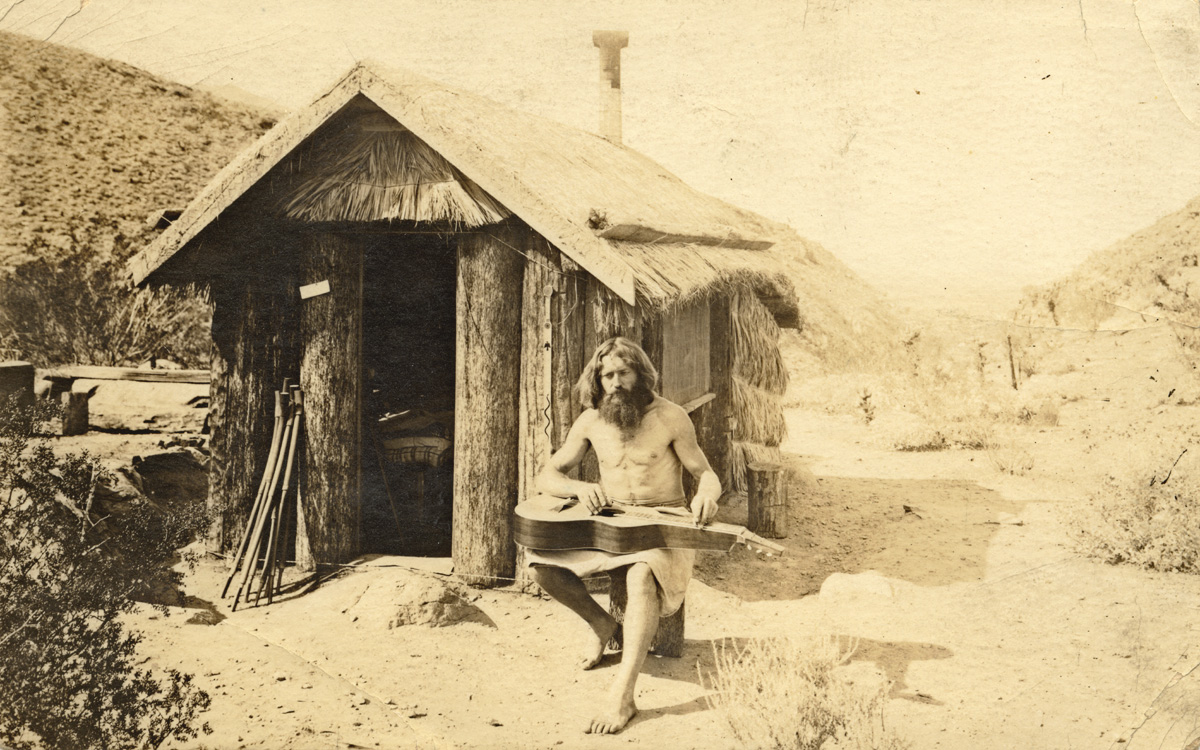

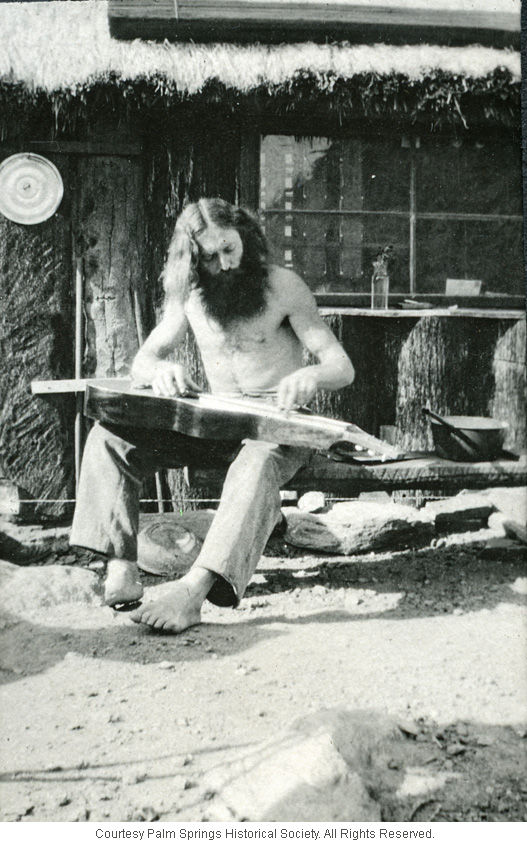

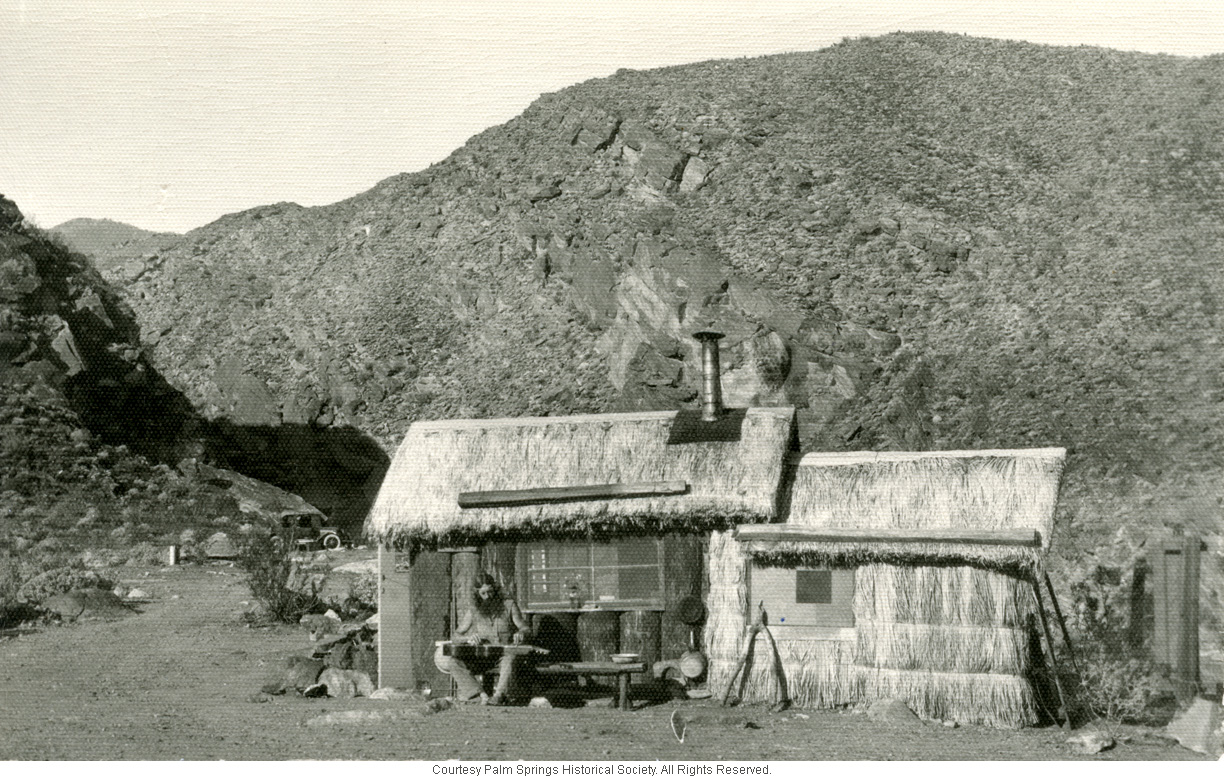

By now, you’ve undoubtedly noticed something peculiar. The guitars in our first two iconic images of Pester are not the same! (Remember that for years we only had a small, fuzzy image of the original Pester photo at the top of the page, so I hope you’ll cut me some slack…) Over these last dozen years, a few other rare images of Pester have come to light from various sources. As I noted each one, I naturally assumed they showed Pester with the same Knutsen guitar, as the desert setting by his palm hut was virtually the same. (A study could certainly be made of the many photos of Pester’s home and its surroundings, which could probably help date them.)

What was originally the fun part – trying to identify additional characteristics of “the Knutsen” – soon became a new challenge: trying to decide if each new pictured instrument even was the “key” Knutsen. How many steel guitars did Pester own?

Pester Mystery Steel Guitar #2

After a dozen years since first discovering Pester, I decided (in light of the first serious study I was now conducting, prompted by last week’s “Nature Boy” topic) that it was finally time to go to the source and try to get all the resolution I could on these guitar images. After contacting the PSHS about obtaining high-quality digital scans and use rights, Nicolette Wenzell, the friendly and amazingly helpful Associate Curator and Collections Manager, quickly found the four images I had requested…along with eight more photos of Pester with a guitar. I’ll be sharing most of these below.

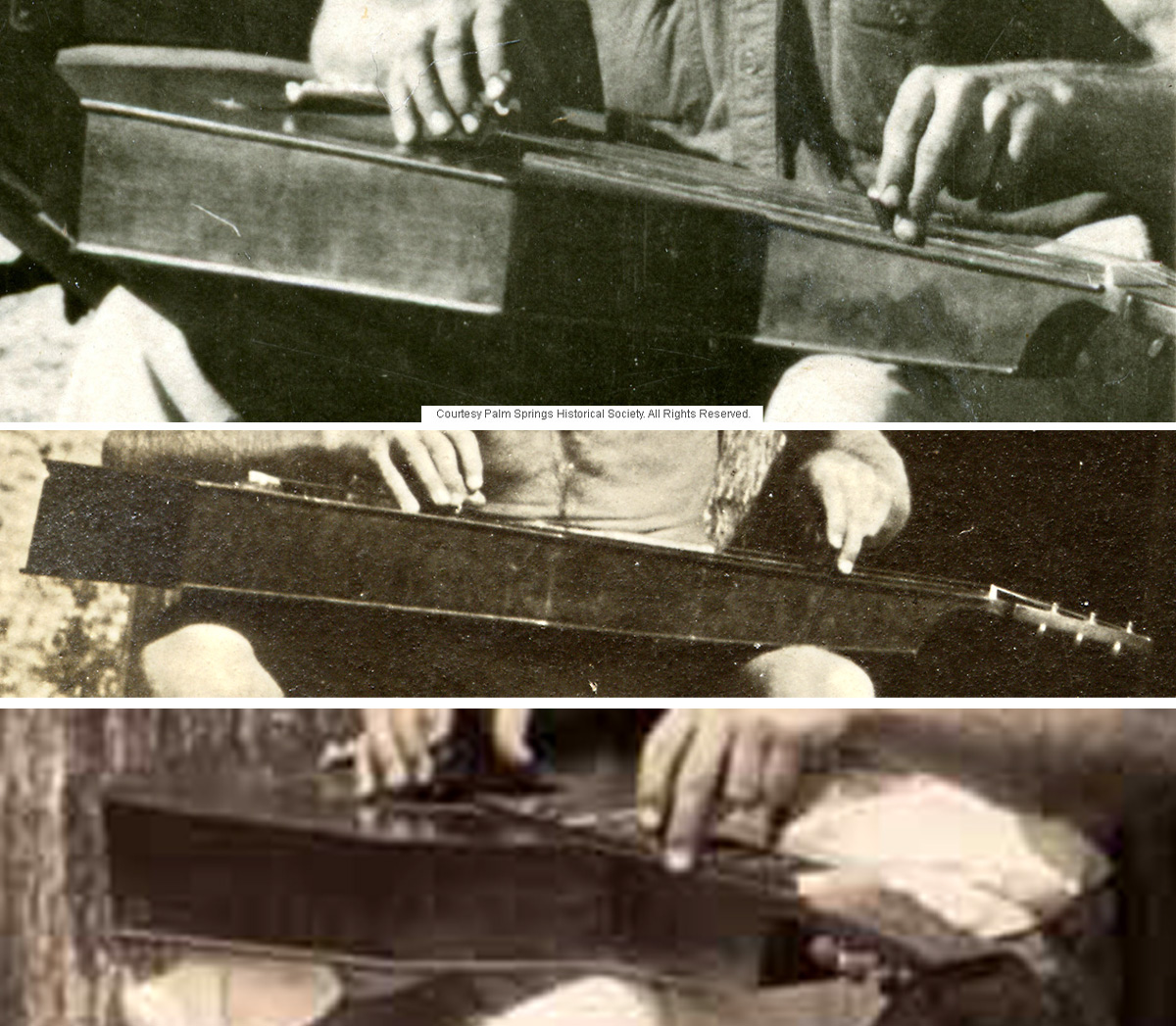

Interestingly, none of the new photos seem to show the “key” Knutsen. What they seem to show is a second Hawaiian guitar – quite likely also a Knutsen – that matches our very first discovered Pester guitar at the top of the page.

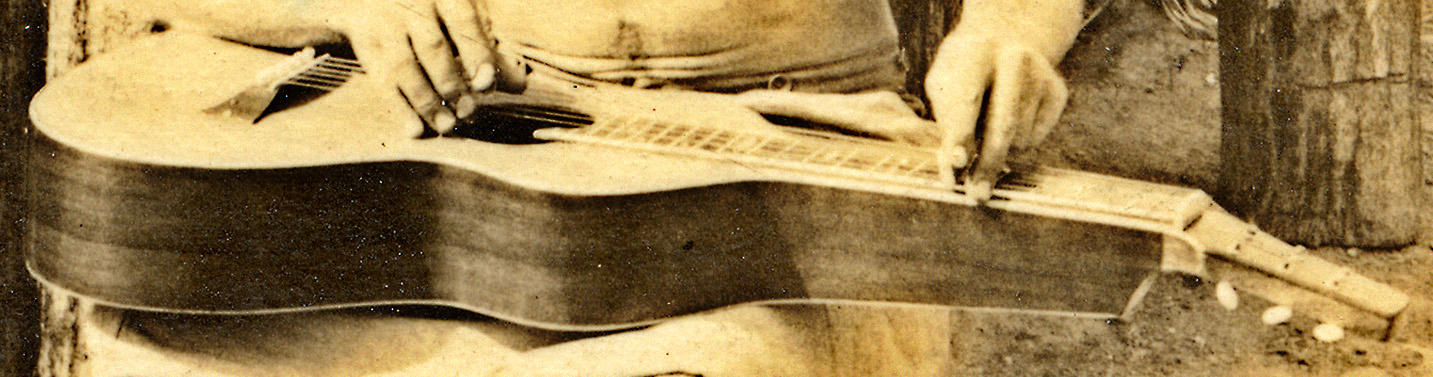

The many photos of this second instrument appear to be consistent with each other, and include a lack of binding and slightly shallower body. The final differentiator was the position of the tuning posts on the headstocks, noticed by Tom Noe, who explains, “In (the “key” guitar), I note that the 3rd & 4th string tuning posts are positioned about two inches from the end of the headstock, with the tuning gear and its button positioned between the tuning post and the end of the headstock. In (the) other photos, these components are reversed, and the tuning posts appear to be closer to the end of the headstock with the gear and button positioned on the instrument side of the post.”

Top: Bound “key” Knutsen. Bottom: Unbound attributed Knutsen

Top: Bound “key” Knutsen. Bottom: Unbound attributed Knutsen

In the comparison above, you can see what Tom explains, along with the body depths, taper of the hollow neck to the head, and bound fingerboards – the second instrument possibly having a similar extension also.

The main reason we’re thinking Knutsen for this second instrument also is the same argument about body depth in the bullet list above. From what we can see, it also appears to have a similar fingerboard and bridge. Here are three views that show the butt of the instrument with a distinctive maple (?) seam. Looks like the bone endpin got lost in the third image.

It would make our lives much easier if all (or any!) of these photos were dated, but we can only guestimate most of them. The key Knutsen photo is thought to be c.1917, which seems reasonable, while the second attributed Knutsen appears in photos that may range from the same period to c.1921.

Here are two images that are included in a dated scrapbook archived by the PSHS, made by one John Sensenbrenner, who was in Palm Springs for his health in 1919, according to his son.

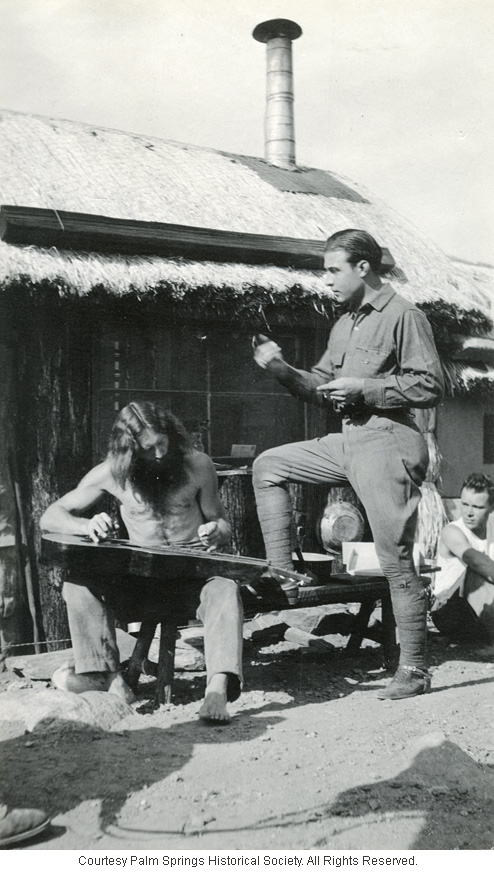

You’ve all seen the famous photo of Pester playing for Rudolph Valentino during a film shoot in my previous article. Here are two more, taken at the same time.

The Valentino photo has been attributed as c.1920 and c.1921. My wife, a Paramount Studios costume archivist, and her colleagues were able to identify the film as The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. It was released in March 1921, and reported to have been filmed over a six-month period. This would place the photos exactly as previously attributed − anywhere from late 1920 to very early 1921.

And yet, if you compare the first Valentino photo above with the second Sensenbrenner scrapbook photo attributed to 1919, it looks as if they were taken at the very same time. Frustrating trying to resolve all this, isn’t it? Yes, but there are clues. Alert reader Tom Walsh noticed that the shadows on the ground of the Sensenbrenner photos appear to be that of the horse and reins in the Valentino photos (see his Comments below). That would suggest that the Sensenbrenner scrapbook images date from the day in 1920/21.

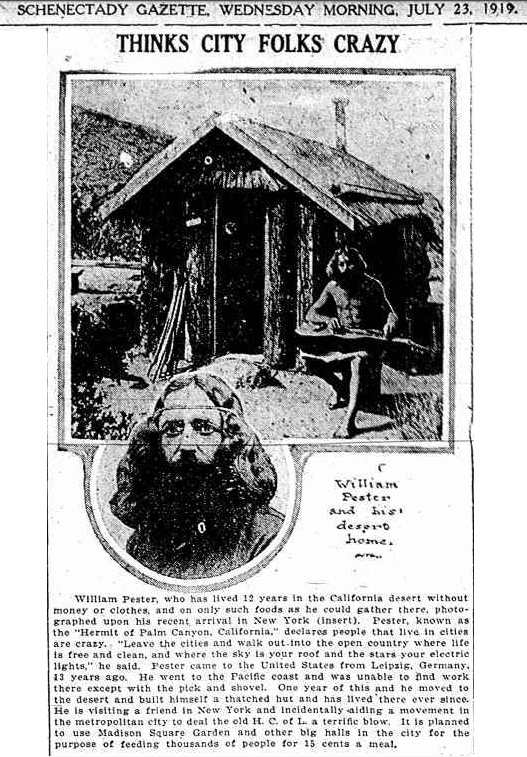

Biographer Peter Wild put Pester at his Palm Canyon desert home beginning in 1916, with acknowledgment of a possible earlier trip or arrival “by 1907.” It seems that the only clue for the earlier date stems from Pester himself, who in the summer of 1919 told various reporters that he had been “living in the southern California desert without money or clothes” for “12 years” or “13 years” (which wasn’t strictly true, it turns out).

Dozens of similar short articles, always with an image of the hermit, appeared in newspapers far and wide during a trip Pester made to New York in June/July 1919 (stopping off in Chicago just long enough to make a similar impression there). Here’s a typical example:

Note that our “key” Pester w/Knutsen image was used by this paper, proving it to be at least a pre-1919 image and that Pester was presumably supplying reporters with photographs or postcards. The inset picture was allegedly taken in New York (Pester would have been 34 years old).

Many papers included this next photo with their story, of which this is the best resolution I could find. It is the only other photo we have that clearly shows Pester with what must surely be the key Knutsen number one.

When and where was the photo taken? Did Pester supply the photo? Or was it taken by a photographer in New York (which would indicate that he traveled with this Knutsen)? Perhaps only an original A.P. file photo would resolve the question (is that his hut in the background or the N.Y. train station…?).

Curiously, the caption ends with another Pester claim – that he made the guitar in the picture himself “from wood found near his desert home.” Certainly, Pester didn’t build his own perfect Knutsen replica in his desert hut. He couldn’t have actually built a guitar on his own…

…or could he?

…

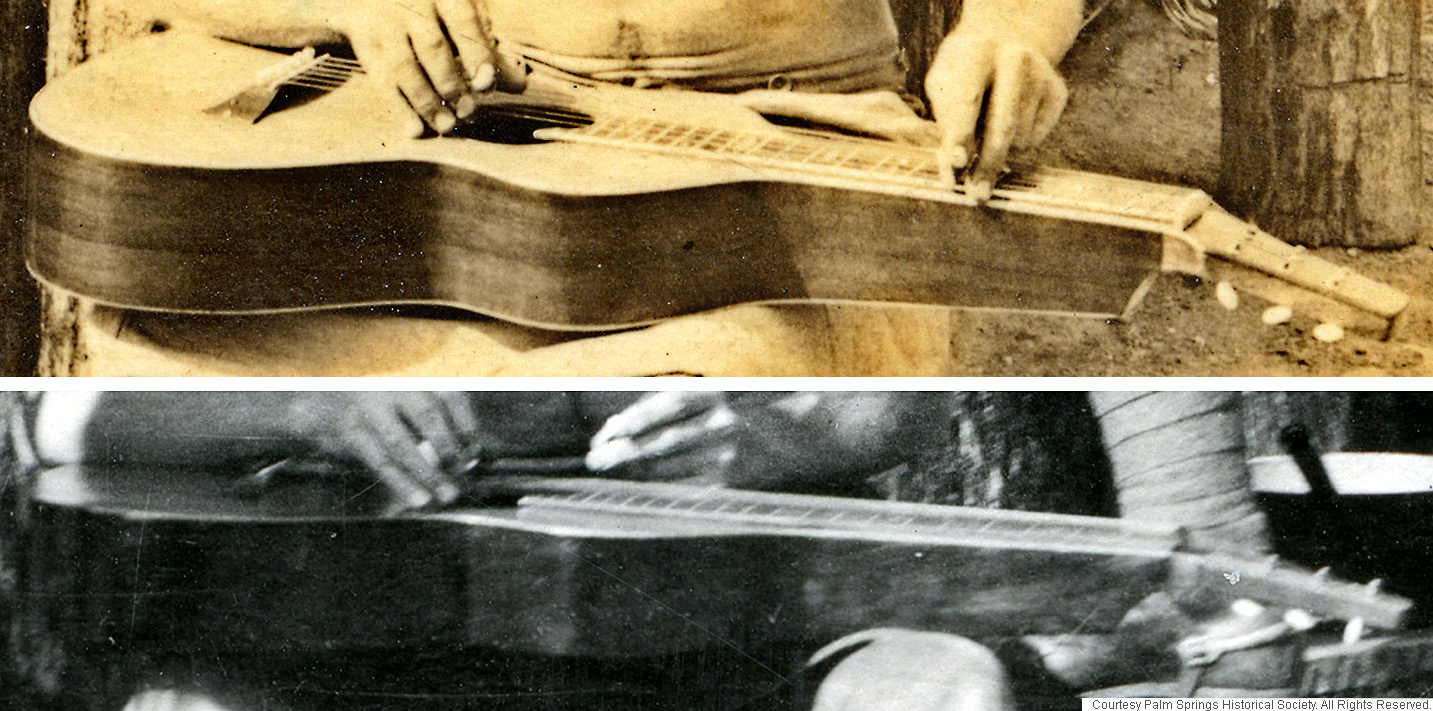

Pester Mystery Steel Guitar #3

When I acquired this original Pester postcard some time ago, I added it to the Archives but didn’t spend too much time studying it (or maybe I did, and again became frustrated and gave up). I assumed it was the second attributed Knutsen.

Then I saw the curious photo from eBay this year (shown at the start of Part 1), and, with the low resolution and thought I was looking at a rare Knutsen box-shape “pineapple” steel guitar. Realizing it was likely the same instrument as in my postcard above, I took a closer look and realized that this was not a Knutsen guitar at all. In fact, it was no known maker’s instrument! Perhaps this was the homemade guitar Pester alluded to in New York?!

By great good fortune, the PSHS had a third image of this remarkable instrument, seen clearly in a photo circa-dated 1920:

What I had at first taken as binding turns out to be a strange, “fiddle edge” top and back, a sort of half- or quarter-dowel shape that overhangs the sides. The sides may not be bent at all but flat boards joined together. If Pester built this with simple tools and techniques, how did he carve and join the hollow-neck slope and headstock? To me, it looks like he salvaged this section intact from his second attributed Knutsen above. Of course, for that to have happened, we’d have to disregard the “1920” written on this image and hope to be able to date all three of these images later than the Valentino photos.

Thoughts?

Below are the three shots of (I believe) this same curious instrument.

I’d love for you luthiers to tell me how Pester might have constructed this thing either from scratch or from a busted Knutsen in his desert hut…

Pester Mystery Steel Guitar #4

Our final Pester guitar is pretty exciting. Though it appeared in both Kennedy’s and Wild’s books (discussed in Part 1), this is its first web publication. The instrument doesn’t appear in any photos of Pester in the desert, only in this single studio shot:

If your brain’s shouting “Weissenborn!” then you’re absolutely right.

In fact, a Weissenborn “missing link” that shouldn’t exist, according to expert Tom Noe. I’ll get to his interpretation in a moment, but first, to help try to date the photo, we need to investigate Pester’s life and times a bit more.

I have often wondered: How did Pester the hermit wind up playing a Knutsen steel guitar out in the desert near Palm Springs? Peter Wild’s recent book finally gave us some clues.

As I mentioned above, it seems that Pester wasn’t actually living in the desert full time – at least not from 1907-1916. He tended to wander, and sometimes wander far. For example, he apparently traveled to Brazil in 1921 and in 1922/1923 and possibly much longer, he lived in Mexico. What interests me is his period in 1914-1915, when he spent a year in Hawaii.

Though we have no idea if he was a musician of any sort before he left and though there are no records of his time spent there, surely it’s a pretty safe bet that he heard Hawaiian music and also discovered the steel guitar on the Islands.

Pester sailed to Hawaii from San Francisco, and though he listed “Los Angeles” as the return destination on his manifest, he actually returned through San Francisco, a fact discovered after I published the article by Tom Walsh (co-author of the recent book on Martin Ukuleles, so well versed in thorough scholarship). Both biographer Wild and I had not discovered that. Numerous articles talked about how Pester expected to be able to live off the land, but was “ordered to move on” from Honolulu, then tried Kona (didn’t work out as he was forced to pick coffee to earn a wage), so eventually returned to the mainland.

The upshot to all this is simply that Pester landed in San Francisco in August, 1915, when the city’s famed Panama-Pacific International Exposition was still in full swing. With its Hawaiian Pavilion with daily Hawaiian music performances, I now wonder if Pester managed to attend and thus get a good glimpse of steel guitar there – perhaps even Knutsen’s.

The Hawaii news articles included several mentions of Pester planning to return not to San Francisco or Palm Springs, but “Los Angeles.” This is was I think is worth exploring. After all, Pester surely didn’t find his Knutsen guitars in the Palm Canyon desert.

He almost certainly discovered them in Los Angeles.

Pester was no stranger to L.A., and lived in the city at one time, perhaps even keeping a room or “home base” there. We even have the address: 823 San Julian St., smack in the middle of Weissenborn/Knutsen territory. Biographer Peter Wild’s sleuthing uncovered the fact that Pester was listed as a lodger there in the 1910 L.A. City Directory (working there as a laborer during this time), and also later listed this address on his 1918 Draft Registration Card.

Interesting… So it seems Pester found himself in downtown Los Angeles on possible multiple occasions – in fact, at the same address, eight years apart. It might be logical to assume then that he would return to these same lodgings or at least the same neighborhood, so for speculation’s sake, let’s imagine Pester returning to downtown Los Angeles in August 1915, with Hawaiian steel guitar music still dancing in his head…only to discover one of the country’s preeminent steel guitar teachers and two new steel guitar builders nearby!

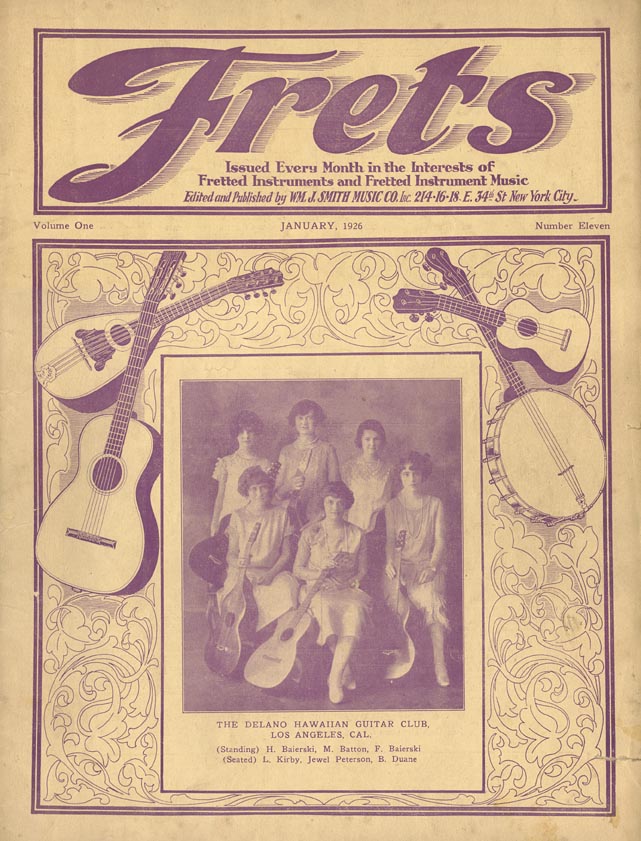

As it happens, even as Pester was visiting Hawaii, both harp guitar builder Chris Knutsen and piano refurbisher/musical instrument maker Hermann Weissenborn were setting up new shops in Los Angeles. According to Tom Noe, Knutsen had moved from Seattle in 1914 at the behest of active Los Angeles teacher/composer/group leader/steel guitarist Charles DeLano.

Courtesy of the Special Collections Department, University of Iowa Libraries. Copyright Images from “Traveling Culture: Circuit Chautauqua in the Twentieth Century”, a database of text and images drawn from the Redpath Agency Papers at the University of Iowa Libraries, Iowa City, Iowa. Used by permission. All Rights Reserved.

Courtesy of the Special Collections Department, University of Iowa Libraries. Copyright Images from “Traveling Culture: Circuit Chautauqua in the Twentieth Century”, a database of text and images drawn from the Redpath Agency Papers at the University of Iowa Libraries, Iowa City, Iowa. Used by permission. All Rights Reserved.

After making some amount of instruments specifically for DeLano (above photo, 1916), Knutsen was given the ax, so to speak, and DeLano contracted the Shireson brothers and ultimately Weissenborn to be his sole supplier (photo below, from 1926).

Courtesy of Ben Elder

Courtesy of Ben Elder

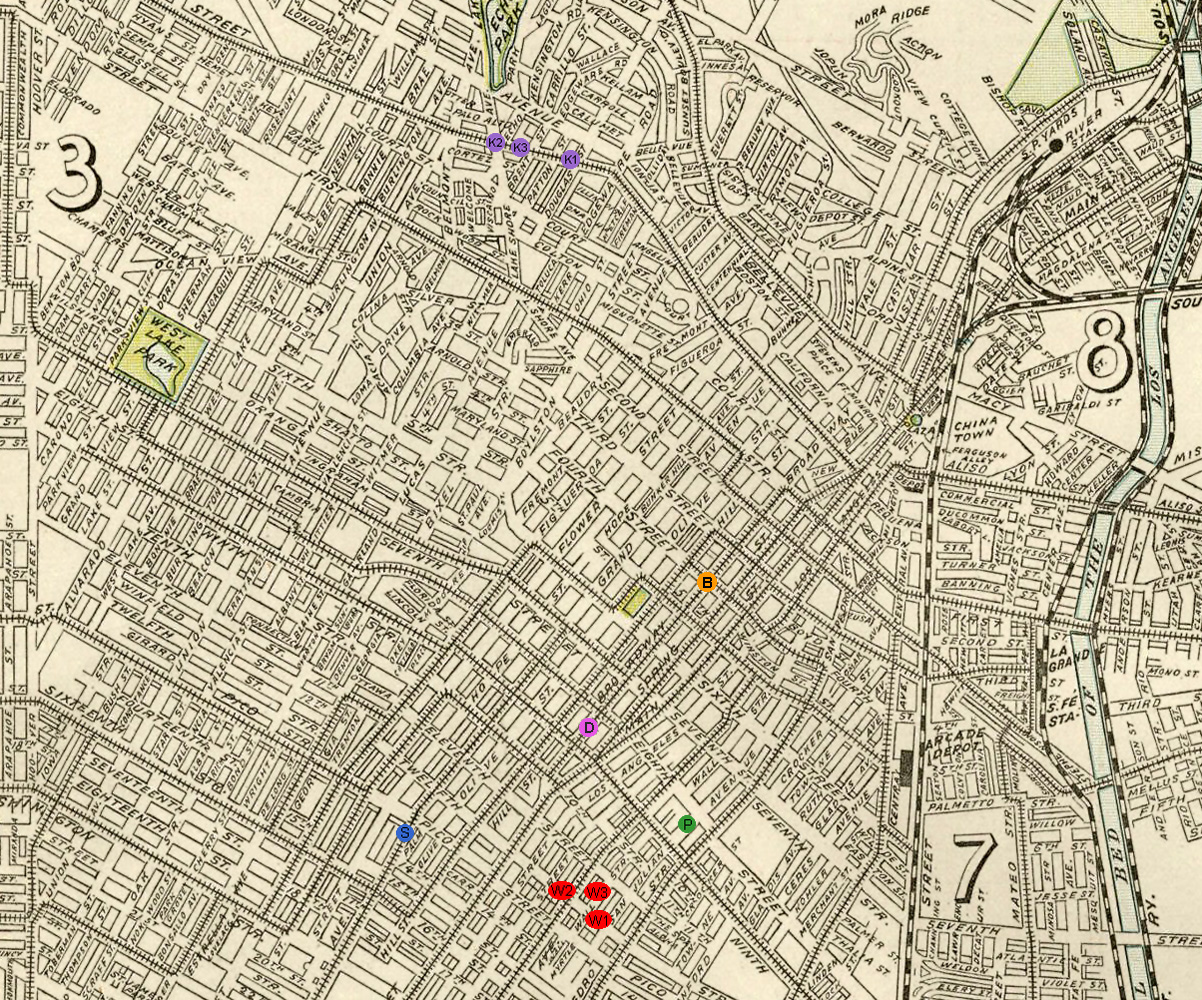

Curious about all this seeming serendipity and to explore my hypothetical Pester scenario, I re-created their neighborhood using this 1899 downtown area map (which didn’t change significantly during our 1915-1920 study period).

- The green dot is where Pester lodged in 1910, still used in 1918, and possibly stayed at other times throughout the ‘teens.

- The pink dot was DeLano’s studio from the fall of 1909 through at least 1917.

- The red cluster represents Weissenborn’s addresses in 1912, 1917 & 1919.

- The blue dot is not musically relevant, but an interesting side note: the Naturopathic Institute of German Dr. Carl Schultz, at this location from 1905 into the 1920s. Schultz is described in Gordon Kennedy’s book just before his chapter on William Pester. It’s certainly possible (likely?) that Pester was aware of Schultz. If nothing else, perhaps he stumbled upon DeLano or Weissenborn simply by walking past their doors on the way to visit the Institute of his “natural” compatriot.

- The orange dot was the location of the Broadway department store, which believe it or not stocked a full line of Knutsen instruments at one point. In August, 1917, they announced a sale on these instruments. For just $17.50 and $22.50, Pester could have bought the two (presumed) Knutsen steel guitars he took back to the desert with him.

- Or, just as likely, he could have made the short trolley ride to visit Knutsen himself and make his selection there (the purple dot cluster, K1 being his son-in-law’s home where Knutsen quite likely lived and worked when first in L.A., then K2 & 3 being his 1916+ home and workshop).

Downtown Los Angeles in the ‘teens: Broadway & 5th, not too far from Pester’s haunts. Can you imagine the looks he would have gotten?

Downtown Los Angeles in the ‘teens: Broadway & 5th, not too far from Pester’s haunts. Can you imagine the looks he would have gotten?

To me, then, it seems more than plausible that William Pester, the Hermit of Palm Springs, spent some time in Los Angeles before heading back to the desert with supplies and a Knutsen Hawaiian guitar or two. This would have been an ideal time for him to arrange his portrait studio session as well, the outcome of which was to print up homemade postcards to sell to tourists (as seen in Part 1, Pester became something of a Southern California attraction). Again, he didn’t do this in the desert, though he could have perhaps accomplished it in Palm Springs.

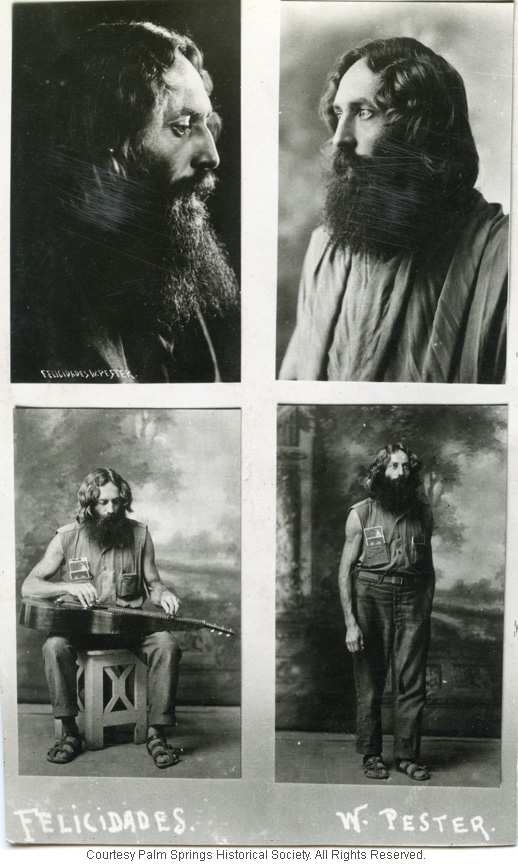

The Palm Springs Historical Society has two ultra-rare original Pester postcards, one a single image with the Weissenborn, the other with four photos crudely arranged and composited onto one card. Printed on the back are some of his simple life & health tips (written in Spanish, for reasons still unknown). Presumably, all four images are from the same studio/printing session; what’s sticking out of his pocket in the two lower photos appear to be the very headshots used above! These postcards are assumed to be those that Pester sold as souvenirs to his growing number of desert visitors and tourists. One has “1922” written on the back, but there’s no way to know what that might actually indicate. I think they show a younger Pester (he would have been 31 in 1916 for example), and my gut says he had them made up before heading back to the desert by late 1916 – though a later city visit during the next five years would not be out of the question either.

The unusual Weissenborn fits this time frame as well, according to expert Tom Noe. In fact, Tom’s analysis includes the intriguing idea that Pester may have actually commissioned the instrument – requesting the deep body of a Knutsen – thus contributing to the development of steel guitars! I had envisioned something simpler – Pester just borrowing or renting an instrument from his luthier neighbor – mainly due to the fact that the guitar never showed up in the desert or in any other Pester photos (and he did have two other Hawaiian guitars, besides). That’s not to say he couldn’t have bought it and left it in the city.

If so, Pester seems to have suffered from G.A.S. (Guitar Acquisition Syndrome). How could he have afforded all these instruments? Well, Pester was a hermit, he wasn’t a bum. He could and would find work when he needed to, and was quite the little entrepreneur in the desert, selling postcards, handmade walking sticks, locally-collected arrowheads, and charging visitors 10 cents to look through his telescope (another seemingly extravagant expense). He also lived incredibly frugally. In 1927, he retired outside Indio, California, where he bought ten acres of land for $600, paying entirely in gold coin. Just think of the guitar collection he could have had instead!

The crown jewel could have been this deep-bodied “Style 4” hollow-neck Weissenborn. Here’s what Tom Noe has to say about it:

“Here is what I can tell you about the Pester Weissenborn (assuming that c.1916-17 is accurate). The 1916-17 period was transitional for Hermann Weissenborn. Up to that point, virtually all his guitars (I’ve documented 24 of them) were based on the Style 2 platform with thin bodies, varying from 1-inch depth to 2.5 inches deep. These included the early maple and spruce guitars, but by and large, most of them had koa wood backs/sides with spruce tops. Around 1916 or so, Hermann began building guitars with solid necks, which I personally believe were built to offer DeLano an alternative to the Knutsen convertibles and what eventually became the Kona guitar.

“I was very fortunate to obtain from Red Bower the solid neck with Style 4 appointments because historically it is one H.W.’s first guitars with full Style 4 treatment. On the other hand, Pester’s Weissenborn, which appears to be brand new in the photo, is the first full-size hollow-necked Style 4 that I am aware of. Weissenborn built a very few other deep-bodied guitars over the years, notably Chris Merwin’s fat solid neck and Jon Kellerman’s “corpulent” late ’20s Style 1, but a 3-inch body depth became the factory standard. Building that oversized guitar for Pester may have been the catalyst for Weissenborn to abandon his early thin-bodies and look for a more optimal body depth.

“(I say) c.1916-17 because it has the hallmarks of the solid-neck guitars Weissenborn built. It has the dark red-tinted finish treatment and the fine rope binding. The dead giveaway, however, is the half-inch thick headstock with tuners designed for slotted headstocks. In the mid-teens, Weissenborn got a batch of Waverly slotted-head tuners with waffle-ended plates. Practically all of the H.W. guitars of this period used them – virtually all the solid necks, some guitars, and even some Konas. That being so, it is the first Weissenborn without a solid neck that I have seen with Style 4 appointments, and, I believe, a defining artifact in the evolution of Weissenborn guitars. That thin headstock never (don’t say never!) appeared on a factory guitar from the 1920s.”

Courtesy of Tom Noe. All Rights Reserved.

Courtesy of Tom Noe. All Rights Reserved.

“Here is an example (above) of a 1916 Weissenborn solid-neck with the Waverly waffle-ended-plate tuners that were prevalent on his guitars in the 1916-1918 time frame. Note that the headstock is only 1/2 inch thick to accommodate these tuners, which were designed for slotted headstocks. Also, notice where the string hole is and how “tall” the tuning posts look. This is the same thin headstock on that fat Style 4 Pester is playing.

“The factory standard headstock thickness for Weissenborns is 5/8 inch because tuners designed for solid headstocks were used. The difference is the string hole location in the post. After these mid-teen Weissenborns and some Konas with the waffle-ended tuners, we never saw the thin headstocks again. (I think this instrument) could have been as early as maybe late 1915.

“I would sure like to know whatever happened to Pester’s deep-bodied Style 4.”

So would I, Tom! As you said, never say “never.” There’s always a chance this very instrument will turn up one day. It may lie undiscovered in some downtown Los Angeles building basement.

Or does it lie buried under the desert sands near “Hermit’s Bench” outside Palm Springs?

Special thanks to: Nicolette Wenzell and the Palm Springs Historical Society, Tom Noe, Ben Elder, and all the past and present Harp Guitar Foundation donors for providing the opportunity to acquire and present this material.

Weissenborn & Knutsen steel guitar fans: we need you!

First, please note and observe the PSHS copyright on all their images above.

Second, feel free to weigh in on any of the identification points I present in the article (with specifics, please). If you have or know of rare instruments important to this study, please share!

Lastly, if you enjoyed this article, or found it useful in your research, please consider a tax-deductible contribution to the nonprofit Harp Guitar Foundation, which helps make this work possible.

Thanks!

Gregg Miner

Wow, great stuff Gregg! I have nothing really to add from my research, though – he doesn’t seem to be the Foursquare type! I will do a search through the KHJ archives to see if his name comes up. I agree it’s likely he simply bought his Knutsens from the Broadway sale. Though who knows, maybe after a nice stroll by Echo Park lake..

Also, the luthiers can confirm, but I don’t think it would’be been THAT hard for him to cut that curve on the homemade guitar. It could’ve been easily accomplished with a bowsaw, which he may have had from making the cabin. So I wouldn’t say it was necessarily a cannibalized Knutsen neck. Oh, and while I’m guessing you already know this as a mandolinist, the proper “geek” terms for the tuner configurations are “worm over” and “worm under” (for the position of the worm gear relative to the post).

Finally, I loved this quote from Vol. 1, it must be the motto for all Knutsenologists: “just because we don’t have evidence for it doesn’t rule out a hypothesized event from having happened”

Excellent arcticle – fascinating stuff! One thing I noticed in the photos – in the Sensenbrenner photo and the other one with Valentino, you mention it “looks” like they were taken at the same time. I would say they were certainly taken at the same time. There appears to be a shadow on the ground of a horse, including reins, and the shadow can be seen in both photos.

Thanks, Tom – I think you’re right!

Just goes to remind us that nothing with handwritten or “remembered” dates on them is fully reliable.

5/25/14: I made some edits to the article after Tom’s observation. I also made changes to the section about Pester’s return from Hawaii, as Tom also discovered that Pester landed in San Francisco, not in L.A. This may or may not have signifance depending on whether Pester stopped off at the PPIE, where we know DeLano performed, and which Weissenborn and Knutsen might have certainly visited.

This is simply one of the best articles you have ever written, Gregg. Nerdy and exciting and funny in one big cocktail. Super!

– Thomas

Wow Gregg! Fantastic piece of work.

Isn’t that “coffin” shaped guitar interesting.

Could it have been a custom made one, to his specifications?

Thanks, Sean.