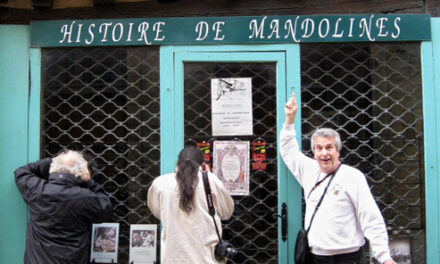

A couple of weeks ago, Alex Timmerman (who incidentally is one of the very few serious harp guitar historians) posted the photo at right on his Facebook page and it reminded me of an important and long-delinquent article on my “To-Do” list!

If this remarkable-looking instrument looks familiar, it may be because it was the very first Harp Guitar of the Month on this site. Amazingly, before that piece (July, 2004), the instrument had never been seen by the public.

My original article explained how I tracked down its identity from a single obscure reference in a hundred-year-old German book (Sachs), after which it was located and photographed by Benoit Meulle-Stef, a fellow harp guitar fanatic who just happened to live a stone’s throw from where the instrument had long lay unseen and unstudied: the Brussels Musical Instrument Museum.

When my wife and I planned a trip to visit Ben in the summer of 2007, a visit to the museum was of course a must, but Ben was also able to arrange a private appointment with the curatorial staff so that I could see this strange instrument, along with two other ultra-rare off-exhibit harp guitars.

Interestingly, just before our departure, it developed that I had become additionally keen to examine this particular harp guitar for another reason. On the old “Guitar Summit” forum (for “early guitar” scholars), there was discussion of a curious newspaper announcement published on September 5th, 1803 of a guitar concert to be given by virtuoso Mauro Giuliani two days later. Besides guitar, Giuliani described a new instrument he was to perform on: a “chitarra francese con Arpa a 30 corde.” Giuliani scholar Thomas Heck translated this as a “guitar-with-harp,” noting that chitarra francese was the fancy new name for the six single strings Naples-manufactured “French guitar.” A purely hypothetical twelve doubled bass courses was his best guess as to the rest of the mystery instrument (others wondered about theorboed bass strings also, or even “sympathetic strings” as in the bowed Baryton).

Benoit and I couldn’t envision those options. Instead, Ben pointed the Group to this instrument as an example of other experimental instruments going on at that time. As expected, some forum members were curious, while my arch-nemesis (initials withheld, but his Modus Operandi is well known) scoffed, calling the instrument a “monstrosity.” Mind you, we were not proposing this as the actual candidate, but a possible conceptual example (by the way, the Brussels HG has 31 harp strings next to the 6 guitar strings). To date, no one has uncovered or deduced what the Giuliani instrument may have been.

So I was thus anxious to see if Ben and I could determine if it was in fact a “real” instrument or not…

July, 2007, and I got my grubby little hands on it! Well, that’s not completely accurate – we were limited to the “white glove test.” The curatorial staff was incredibly helpful and accommodating, and as interested as we were about these rare treasures.

This particular harp guitar (Brussels catalog #1550) unfortunately remains a mystery. No maker’s mark, date, or any other identifying features – only a past curator’s guess long ago that it was built in England in the first quarter of the 1800s. Reasonable, it seems.

In fact, Ben had already noted how the pilaster cover was similar to that of the c.1840 J. Frederick Grosjean “double harp guitar” (at right). Could it have been built by the London harp maker? Interesting that both are unique “one-off” combinations of guitar and harp. Sachs listed #1550 as a “harpe-guitare,” simply because that was the name the original museum curator long ago decided to catalog it under – and in this case, they were spot on!

Though it does give the impression of a guitar fused to a small harp, like 99.9% of all harp guitars, the extra strings are actually mounted “zither style” in plane with the soundboard, itself just an elaborate extension of the guitar’s spruce top. In our opinion (Ben and I), it is definitely of sufficient quality – design and workmanship – to be considered a “real instrument,” and a lot of time, effort and ingenuity obviously went into it. Yet in practical and ergonomic features it falls short.

And so the thousand dollar question: How does one play the dang thing?! Or (as more than one have wondered), do two play it?

Let’s begin! I’ll first answer the inevitable “How does it sound?” question by stating up front that it was in unaltered original condition and thus in disrepair, the original gut strings not remotely tunable at this time.

Test 1 (top and above): The guitar can be played fairly traditionally, held classical-style in the lap. We immediately noticed the first design flaw however. As you can plainly see, no matter how you play guitar, the lowest adjacent harp string interferes with your left hand. And this isn’t actually the lowest string; one is missing. That lowest harp string would run parallel to the guitar’s high string, an inch or so away from the fretboard. A great visual, but makes playing rather difficult! Perhaps the last owner (over a century ago) had removed that string in order to eke out a guitar chord, as I am demonstrating. Nevertheless, technically, the guitar section could be said to be “functional” in this modified scenario.

In this photo, you can see me pretending to play the harp strings just as we would on something like John Doan’s Sullivan-Elliott 20-string harp guitar. This, too, is entirely feasible – if one has the upper arms of an ape. I could only get about halfway up the thirty-one harp strings, so this would seem to defeat the purpose.

Conclusion: This was my best hope for a functional, musical instrument (using today’s examples). Technically, it’s “do-able,” but unlikely.

Test 2: Just a quick reality check in case it was designed for a lefty.

It wasn’t…

Test 3: Since it’s obviously an ideal standing display instrument, I next checked those positions.

I started on this side, as one has access to the guitar portion. As shown above, I had just enough reach to play the top harp strings, though not comfortably. I could also use two hands to play it as a harp, albeit backwards.

Of course, this scenario is more of an “either/or” option, not both instruments at once.

The guitar was similarly functional but awkward. Just put your guitar up on the counter and try to play it like this. You might get by with simple stuff, but you wouldn’t be giving a concert. The “harp strings in the way of the left hand” problem is also worse.

Conclusion: Ix-nay on this Enario-say.

Test 4: The opposite. Standing at a counter – or perhaps you could sit with it on a small table in front of you – you can play harpist-style reasonably well. It’s a bit cramped up there, but then so are full size concert harps for that matter. Hmmm…possibilities!

Of course, this leaves the guitar out there in limbo. Here is where one could bring in their partner, I suppose, but then they’re back to the unwieldy guitar technique shown above, assuming they can convince you to remove those half dozen harp strings on the bottom end.

Conclusion: An extremely clever juxtaposition of guitar and harp elements, obviously built with a lot of thought, design, calculations, skill and effort…but without apparently consulting either a guitarist or a harpist.

Benoit adds “It’s interesting to see all the guitars made in this period that mimic harps; I’m not sure if it was to achieve their sound, or to follow the “harp craze” of that era.”

You can see the care and viable construction techniques that went into it – and I love how Sachs referred to it as “slightly worthwhile construction.” Note the tiny soundholes in the back and front of the harp soundbox…but look at its top “adjustable sound ports”! Someone was definitely after tone, and expected this thing to produce music.

Another clue pointing to intended usefulness and musicality are the sharping levers on some of the harp strings, in the style of hook harps.

Surely this wasn’t just an elaborate conversation piece or something built on a dare? No, I think it was purposeful, and in many ways remains a charming and imaginative experiment – certainly not a “monstrosity.”

I think it’d be worth restoring and stringing (it will never be, of course), just to see what little can be done with it. Probably not a whole heckuva lot, but I still want one!

Next time: More harp guitar wonderment at the Brussels Museum!