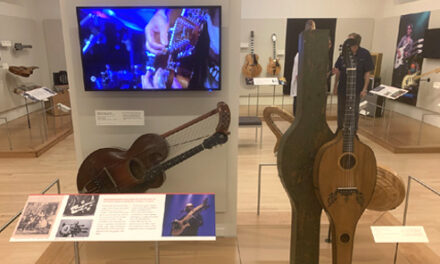

Spoiler Alert: If you haven’t yet read the new issue of The Fretboard Journal (#41, Spring 2018), you might want to do so before spoiling the surprise below. If you don’t have a copy, I’d recommend you run right out and get one (or better yet, just subscribe!). It includes a piece I submitted early last year on the wonderful recently-discovered Orville Gibson harp guitar. This is the one currently on display in Carlsbad at The Museum of Making Music’s harp guitar exhibit (closing at the end of April, do not miss it!), used for their main promo image and also on the cover of our exhibit catalog (which contains a different write up on the instrument).

To accompany the FJ article, I’ve created this addendum to include a few more key photos and additional fascinating elements – including photos of the insides during its repair, a color-coded image of the wood joinery, and finally, a sound sample of the rare instrument.

Again, I highly recommend reading the FJ piece first to learn about the discovery and our subsequent analysis of the instrument, then coming back here to my blog. (FJ excerpts below are shown in “blue quotes”)

FJ: “It all started with that astonishing silhouette.” This one:

I included this reference in FJ: “Peggy Joyce Brumbaugh, author of the long-awaited biography Orville H. Gibson – A Peculiar Excellency.” Despite her best efforts, Peggy’s book has not yet been published; she’s hoping for this summer.

Restoration

FJ: “While Steve has it open for our convenience, let’s take a closer look:”

The following photos came from luthier Steve Helgeson of Eureka, California (sadly, the resolution wasn’t good enough to include in the FJ piece). He took them during the repair process, and unless Phil decides to disassemble it yet again or have it X-rayed, these are the only records we have. So thanks to Steve for providing them and his additional comments during follow-up discussions.

Above: “The beautifully carved top originally had a single short horizontal brace under the sound hole and a simple, smallish bridge plate (Steve [later] added a second brace above the sound hole).” Note how the sub-bass support arm inside the body actually becomes the waist of the body itself.

Below: “While the treble side of the solid rim continued unbroken almost halfway up the back of the neck, it was still an unexpected surprised to see the patent’s hollow neck channel!”

Above: “This curious as-found image of Steve’s shows two long, curved ‘cubes’ of wood at the tail that he thought were original. We believe they are repairs, but very early original repairs, though by whom would be hard to say. And what the failure was (cracks in the rim from dropping?) and why this was their solution remains a mystery. It’s quite a mess from the outside, even after meticulous clamping of molds both inside and out to realign the curved pieces.”

1903 Gibson Catalog Specimens

FJ: “Beyond the catalog illustrations, the only evidence that the original Style U even existed is a single photograph of the ‘Mexican Monarchs’ duo.”

![]()

There are a few versions of this image; unfortunately, all are poor resolution.

FJ: “I wanted to know whether it would match the original catalog specimen…My first goal was getting it positioned in front of the camera as closely as possible to the original February, 1903 Gibson catalog’s Style R-1 illustration…no one had ever suspected that it was anything more than a simple shallow carved relief…Allowing for slight errors in alignment, lens effects, and carving differences, the entire instrument (other than trim) looks like a near perfect match to me, especially the silhouette scroll.”

The rearrangement of the six bass tuners may be the only other noticeable difference.

Orville’s Construction

FJ: “Eventually, I’ll post illustrations depicting the wood assembly seams that I was able to discern, corroborated by Phil and others.”

Despite all efforts, I was unable to get a consensus from professional luthiers about the woods used in the instrument. Aren’t mahogany and walnut completely different?! You would think so, but no – there are large chunks of wood Orville used that give the appearance of seamlessly transitioning from walnut to mahogany, which was botanically impossible last time I checked. Not only does wood identification remain difficult, but locating the construction joints of the 3-dimensional puzzle is still incomplete. I created this image to illustrate all the different seams I was fairly certain about (Phil verified them), but a couple are still unknown and many remain mysterious. The most interesting thing was learning that the support post doesn’t go through and touch the body’s side, it actually becomes the side at that spot! Anyway, take a look at the images, both photograph and color key. I didn’t show the two pieces of the top (which Helgeson thought was spruce, but I’d like a doctor’s second opinion!), as I couldn’t locate the seam…Phil finally was able to just make it out.

The 2 meticulously aligned images below will open in new windows and can expand to a nice large size. Toggle away!

Audio Comparison

FJ: “I’ll post that on my site as a follow-up to this article and let you pick the winner!”

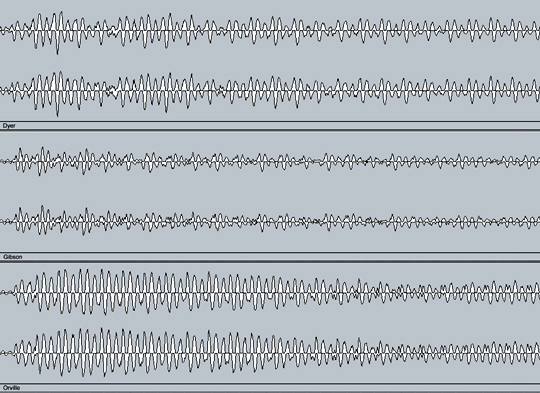

I’m not a huge fan of “sound samples” (as I find recording and playback methods extremely arbitrary), but once I heard this Orville, I became determined to try to at least compare it to other harp guitars. So I put it up against a typical ‘teens Gibson Style U and also my Dyer Style 8. I apologize that it wasn’t a perfect test; I chose to omit re-stringing all 3 instruments with brand new similar strings – cost and time I didn’t have. The other drawback was that I couldn’t risk damaging Phil’s prize with untested tension, so took it very easy, tuning only 1 string bank at a time, and lightly at that. A final drawback was that the outer windings of my phosphor bronze sub-bass strings go nearly to the end, and Gibson’s vintage friction tuner shafts have small holes for the thin, extending (silk & metal) string cores produced in the 1900’s. Thus, I strung up only 3 subs, and without optimum tension.

Still, it’s pretty interesting. For one thing, (apologies to Gibson HG players) the lousy tone of the trapeze-bridge Gibson Company’s U harp guitars ended up sounding different to the microphone than it did to my ear. The weak, odd tone of the neck coupled with decent, bright piano-like sub-basses (to the player’s ear) switched places when recorded at a somewhat ambient 18” distance (not super-close mic’d). Its neck bank was the loudest of the 3 tested instruments, and more pleasant in playback, while the subs kinda wimped out. The listener must remember that the Gibson Co. strung them completely differently back then with ultra-heavy-gauge silk & steel strings.

The Orville-built HG had a very different, much more resonant and pleasant tone from top to bottom. Again, I didn’t have it strung up all at once, and while it seemed to my ear like it would be balanced, on mic the basses are somewhat overpowering. But so cool on their own!

I would have guessed that the Dyer would prove the loudest, but it wasn’t. It also sounds much prettier with new strings, so please cut it (and me) some slack!

I demo’d them by repeating simple chords and bass, while trying to keep my pressure/attack consistent. You’ll hear Dyer, Gibson Style U, then Orville – and then a final short recap (in reverse order) of the neck, then subs. You’ll definitely want decent headphones or speakers for this…

Cubase WAV file of a sub-bass “B” on the Dyer, Gibson U, and Orville

Cubase WAV file of a sub-bass “B” on the Dyer, Gibson U, and Orville

Thanks to Jason Verlinde and The Fretboard Journal for bringing this to a wider audience, The Museum of Making Music for making it accessible to the public during our 7-month exhibit, Steve Helgeson for photos and information, and above all, Phil Rowens for sharing his treasure with us (Below: Phil with daughter Zofia and two pre-1898 Orville instruments).

Fascinating article and sound comparison.

My Gibson 1906 R was constructed with 2 internal support posts and an added tail piece. The neck is not hollow. This article is especially interesting to me. Thanks for sharing.

Great article Gregg. I was going to post something after receiving my FJ today, but you beat me to it. Thanks for the blogg with the additional photos and info. Interesting stuff, even for somebody like me who’s not really a Gibson HG guy. Nicely done!