Yeah, this is probably wishful thinking, but then again, it could be true. We’ll likely never know.

Before 2007, not a single specimen of a W. J. Dyer & Bro. harp mandola had yet been discovered by either Bob Hartman or me. Then within just two years, four of them surfaced! They were all up on my Dyer Plectral Quartet page until I took the increasingly-convoluted mess down last year for a complete rewrite. Feel free to nag me about getting that done; for now, here’s a new stab at the mandola section.

As I had already stated in my article, the serial numbers went only as high as #405 within their 400 series.

This last March, almost ten years since the last one came to our attention, a fifth mandola revealed itself. Listed by a vintage guitar dealer, I was fortunately able to snag it for the museum.

Nice, huh? It’s very clean, with only a back crack, a non-original bridge (and tailpiece, though I replaced it with the correct one), and the typical sinking top above the soundhole. Of the five specimens, mine is the only plain model, the “Style 135.” The others are all the fancy abalone-trimmed Style 145 (not that I’m complaining).

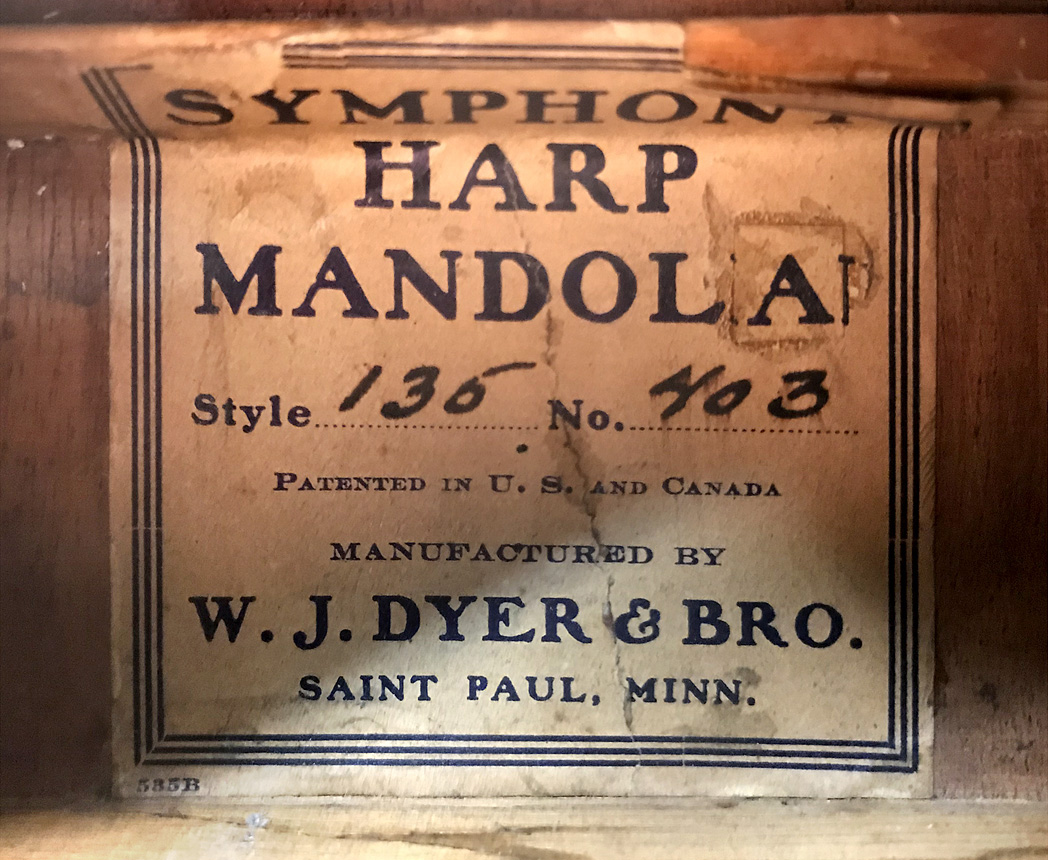

Mine is now the third one found with a label. (To this day l don’t know why so many Dyers harp-instruments are missing – often as if they never had – labels). And so: we now have five mandolas, with serial numbers 402, 403 and 405. We assume they started the mandola series with 401.

It does seem “too neat.” If Dyer had sold as many as one or two dozen of these, the odds of nothing appearing above “5” by now would seem statistically unlikely (though not impossible). It would indeed be interesting if we’d actually managed to catalog the entire output of these (as I think we have also with Dyer mandocellos) – and know their true rarity by exact count…but time may tell.

The above will perhaps be incorporated into the next “final” web page, so let me start a rough draft of that here for the mandolas and then show them.

![]()

We now know that the Larson brothers had been building – and W. J. Dyer & Bro. had been selling – harp mandolins since 1907.

After the late-1890s introduction of sized families of mandolins to correspond to the string orchestra (tenor mandola, octave mandola, mandocello and later, mandobass), mandolin clubs and orchestras quickly became an extremely popular pastime and ubiquitous in America. By the ‘teens, most of the bigger manufacturers had a line of these instruments, including Gibson, Vega, Lyon & Healy, Stahl and many others. While the Larsons had been building the larger mandolin sizes for different manufacturers for some time, it wasn’t until 1917 that W. J. Dyer & Bro. finally decided to jump in, asking the Larsons to create a complimentary “harp mandola” and “harp mandocello.”

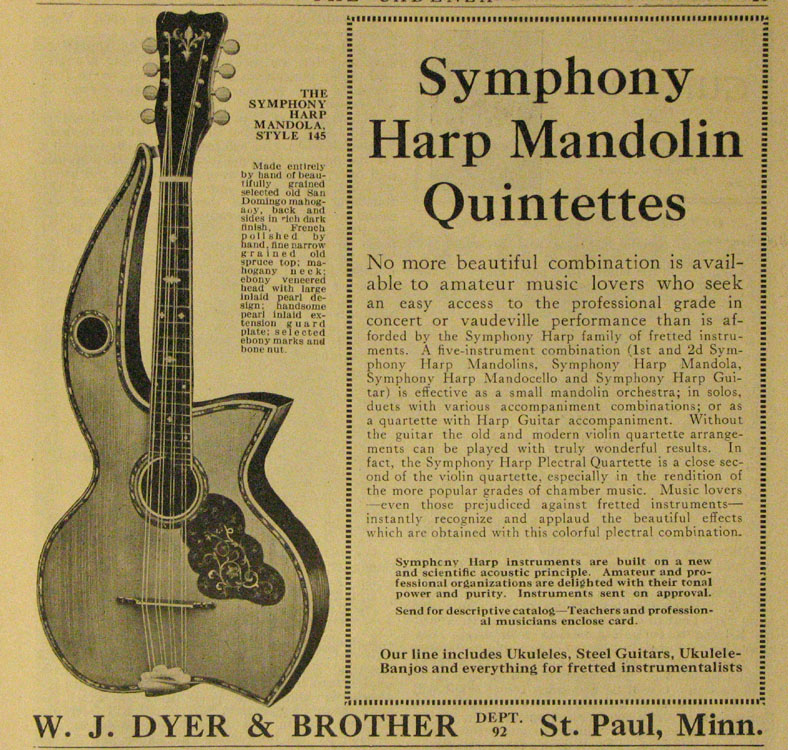

They were mentioned but not shown in Dyer’s monthly ads in the August 1917 issue of The Crescendo, then the September issue of The Cadenza; presumably the Larsons were scrambling to design and produce their prototypes.

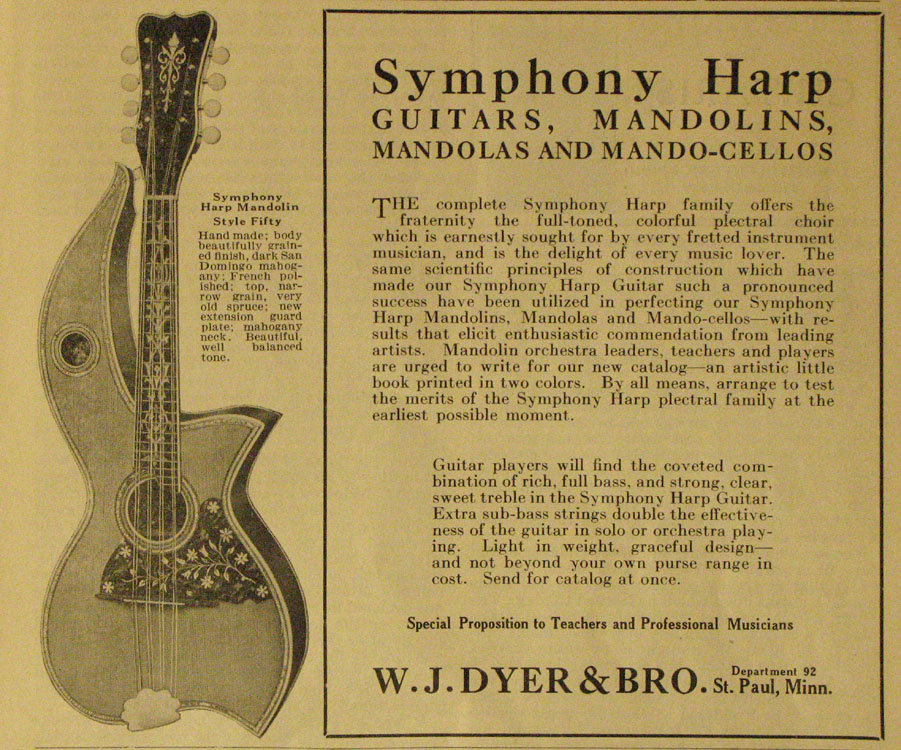

For the next two Cadenza issues, Dyer rolled out their new “Harp Plectral Quartet” (sometimes “Quintette”), but still only picturing their harp mandolin. Finally, in the December 1917 issue, the harp mandola made its appearance (right). Depicted is an extremely accurate engraving of a completed instrument. The harp mandocello took another month or so, appearing in February, 1918.

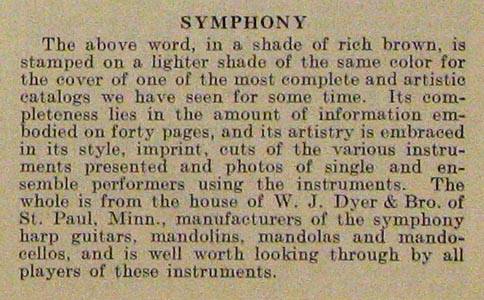

However, our timeline has an additional clue: The Crescendo editors mention the new Dyer catalog in their September 1917 issue. It would seem almost certain that the new mandola and cello engravings would be included in this new W. J. Dyer & Bro. catalog, one which Bob Hartman and I dearly hope to find in our lifetimes. Here is a (rare gushing) review of it in the December 1917 Crescendo:

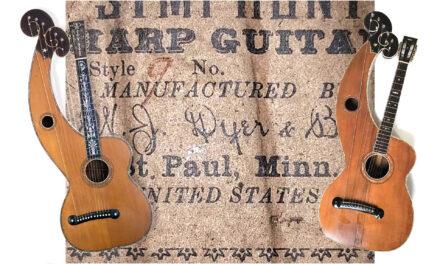

While we wait, we can enjoy this scale image of the harp plectral trio. I am now able to precisely scale the mandolin and mandola to one another visually, and also the ‘cello (friend Ron Petit supplied a single photo with his cello and mandolin [identical in size to mine] side by side).

The ratio is a bit different than I originally had up on the site.

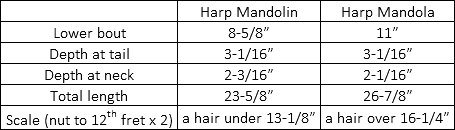

Additionally, here are the dimensions of my two instruments compared:

You might remember that the Larsons re-purposed mandolin labels for the new instruments; Dyer never even bothered to print dedicated labels (another clue that these instruments were decidedly unsuccessful). A piece of paper was glued over the “in” of “Harp Mandolin” and someone wrote by hand an “a” or “cello” to identify the new instruments. Crude, a bit amateurish for a prestigious enterprise like W. J. Dyer (more like something Knutsen would have done!), but got the job done.

Mine is a bit more professional, having an actual “A” cut out of a duplicate mandolin label to paste in and at least have the font match!

As might be expected, with their larger size (though surprisingly, no additional depth) the Larsons’ harp mandolas sound better than their rather unimpressive harp mandolins. I mentioned earlier the “sinking top above the soundhole.” I’ve not seen a single Dyer harp mandolin (and now, mandola) that does not have this flaw. It stems from poor design – rare for the Larsons – who seem to have copied Knutsen’s crude butt joint to attach the neck, with only a small, thin neck block to support this area. They thus cave in (subtly or substantially), causing them to lose their break angle at the bridge, which must surely hurt their tone.

Interestingly, Bob Hartman’s Dyer harp mandolin with a completely replaced top (after the infamous vandal-with-hatchet break-in) sounds utterly fantastic – apples and oranges. (Note to self: Ask Bob to loan that one to someone at G.A.L. to create a detailed plan of the new top and bracing!).

To finish up what was supposed to be a simple blog about the mandolas, here are the five known specimens with my comments:

Specimen A, shared by owner Gary Berry in 2008, has no label. I’ve got it as a hypothetical (placeholder) #401 as it looks like a prototype candidate to me, with its abnormally fat arm (either that or a much later custom order). If true, an absent label might make sense. It would also oblige us to consider whether it represents specimen “0” or “1” (401) in the Larsons’ numbering scheme (hope for finding one more!). The rather eccentric decoration is of course some past owner’s creative if unfortunate customization.

Specimen B is the first one that I became aware of, submitted by owner Tom Ketterman in 2007. It was our very first mandola label, which initially caused Bob and me some confusion due to an obvious “clerical error” – its Style and Serial number inscriptions were reversed! (Note that they also neglected to change it into a “mandola.”) We quickly agreed that the “145” matched the Style 145 given in the Cadenza ad (as did every visual feature of the model). “402” was thus the serial number – representing the second one built or serialized – and we then knew that the Larsons’ chosen series for the mandolas was 400 (which was never used for Dyer harp guitars or mandolins).

Specimen C is mine, already discussed. Please enjoy these brand-new photos. It surfaced just a couple months ago at Willie’s American Guitars. I’m still stunned I was able to snag it before anyone else. Eventually, I’ll address the back crack and how to correct the top sag (volunteers?); not sure about the bridge (first need to choose strings).

Specimen D was actually the first Dyer harp mandola ever seen – the problem was no one realized it! Mandolin Brothers sold it long ago, listing it and selling it as a “mandolin.” Clearly, its label must have been missing and they didn’t pay enough attention to its longer scale and larger size. I spotted their photo in Bob’s 2007 The Larsons’ Creations book, and he quickly agreed (“I was always suspicious”). To this day Bob and I don’t know who owns it, or if they realize what they’ve got! I have this one as “placeholder #404” as that spot is currently empty. It has a couple anomalies: the distinctive mandola pickguard design has some additional area and the ebony with pearl inlay headplate is missing (removed?).

Bob Hartman supplied the partial photo of Specimen E from an anonymous owner in 2009. I’m at least glad it’s a shot of the label! This then gave us our proof for at least five consecutive labels. Some interesting statistics: In Dyer harp guitars, the numerical range of our just over one hundred collected label serial numbers give us a convincing estimate of 500-600 that may have been built (with the many known unlabeled specimens, this is about a 25% “survived and found” rate). Again, it’s curious that the mandolas already enjoy all appearances of a 100% S&F rate!

What about the last Specimen F from the ad? I would suggest that this illustration is accurate and not arbitrary. Meaning that not only should all the trim obviously match (Style 145s were very consistent), but their main variable should match also – the arm tip shape. For whatever reason (omitting a mold section for that difficult bend?), on all Dyer harp mandolins and mandolas these seem to be “drawn (and built) freehand.” Discounting the specimen with the fat arm (A) and the different pickguard (D), this could only match E, which we don’t yet have a full image of (and have lost contact with the owner).

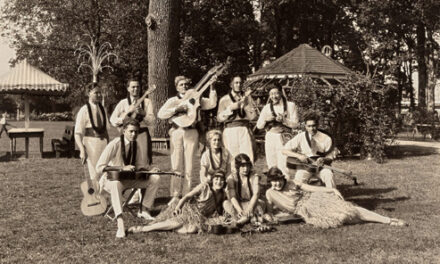

Harp Plectral Quartet rarity, decline and fall: With our current evidence, we know that a few instruments were ordered, built and sold through 1918 and beyond. Unfortunately, Dyer’s timing was off. Not only were they hit by our entry into WWI, they were also nearly the last one into the plectral orchestra market. The craze was already starting to wane (ukuleles and steel guitars, anyone?), the jazz age had begun and by the mid-‘twenties only a tiny fraction of ensembles included mandolins, let alone mandolas or mandocellos (or that once-majestic beast, the harp guitar). Dyer’s last gasp for these instruments was a small mention in their November, 1919 Cadenza ad for Sterling Strings. All were thus likely built over an extremely short two-year period.

Today, over three dozen surviving Dyer harp mandolins are known (not to mention the many vintage photos of musicians with them), but just five Dyer harp mandolas and a mere two mandocellos. I never say never, but would not be surprised if we never add another ‘cello or ‘ola to the count.

Which is going to make finding my final “holy grail” (Dyer’s harp mandocello) a bit of a challenge!