You all know by now that I archive any and all instruments made by harp guitar pioneer Chris Knutsen (though a few slip through my fingers). In fact, I think more come in now because I have two “Google bait” websites up for those searching “Knutsen + harp guitar”: Harpguitars.net’s Knutsen Archives (which I ask owners to submit to), and also Harp Guitar Music, which buys or consigns and sells such instruments. So it doesn’t matter if these instrument owners are just asking about a family heirloom, or looking into selling options, or right down the middle (as many are). Most eventually find me.

One thing that I always ask each owner, no matter what their intentions or background may be, is – do you have any provenance on your great-so-and-so’s Knutsen? Photos, stories, ephemera?

9 times out of 10 (or maybe 19 out of 20), the answer is no. When there is some hint of a true story (and the dates invariably pan out to be wrong), I try to incorporate that into the Archives entry for the instrument. Only a very few major clues have been found this way, but they are always exciting – such as the discovery that Knutsen briefly had a shop in Bellingham, Washington in 1912 (see Inv # HGS63).

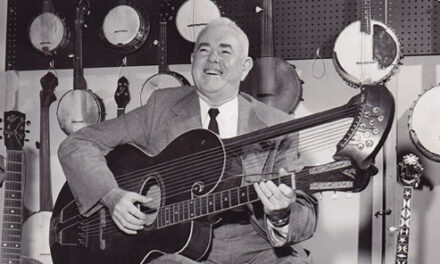

And sometimes, even though there is no specific provenance, it’s just nice to hear something about the past owner of one of these esoteric instruments from the surviving family.

That’s the case here. Gary Ekrom, of Seattle (where his instrument was made sometime between 1906 and 1908), wrote to learn more about the instrument at left that he had long ago inherited from a great aunt. This is just one example of what are undoubtedly countless undiscovered Knutsen instruments (or any harp guitars, for that matter) that lay hidden from public view until their owners have some reason to come forth with them.

As he is contemplating selling it, I asked for photos, and of course, any provenance no matter how slight –

Gary kindly replied:

“It was owned by my great aunt here in Seattle. She was a contemporary of my paternal grandfather who came here as a Norwegian fisherman at the beginning of the century; he settled in Ballard and brought over his family when my father was 8 in 1923. The norm was for several families to own a boat cooperatively and the husband of the woman who owned the harp guitar was a partner of my grandfather. The name was ‘Bjerke’ (Bee-yur-key), and the only thing I know about them was what I overheard when I was about 10. He was prosperous, she was a musician of note who played the mandolin, and when she died my father (who was the executor) got the Harp Guitar and 2 mandolins because my mother was a musician of note as well. The mandolins were a gourd back that has disappeared and the other a Gibson type A that I still have in its original case. There are written materials in that case that I have just gone through looking for clues. Much of it is church-oriented and most in Norwegian. One printed card says ‘Concert, Norwegian Danish Methodist Church, Stewart and Boren Ave., Friday, Apr 26, 1929, 8 PM, Admission $.50.’ I had heard that she was a good player, that she played the Harp Guitar in a manner that listeners appreciated. She may have been my grandfather’s sister given some of the signed docs in the mandolin case. I know it sounds bizarre that I don’t know if this is the case, but Garrison Keillor’s riffs on taciturn Norwegians is not without substance.”

Not much to go on, regarding the instrument, for sure. She certainly could have bought it new directly from the maker – Knutsen being a fellow musician and Norwegian in Seattle – though we’ll probably never know. Note that it is a ¾ size, short scale (19-20”) instrument – suitable for a small woman, perhaps. Of Knutsen’s Seattle-era harp guitars, about a third are ¾ size – he knew how to corner the market! Gary’s great aunt also appears to have had a hankering for super-trebles. I wonder if she knew they were strung “backward.” Interesting that Knutsen reversed the harmonic curve of his treble banks from his earlier Port Townsend/Tacoma models. Why? Well, we still don’t know if he tuned them to a diatonic ascending scale (a la John Doan). He might have tuned them to a pentatonic scale or open chord, for all we know. The direction wouldn’t have then mattered so much, especially if only strummed. Lots of fret wear, so she wasn’t just concentrating on her mandolin! The other cosmetic damage, Gary admits, was caused by him and his friends during the 1950s, when, he says, “we basically treated it like a toy.”

Don’t worry Gary – this instrument can be restored to be treasured and played again!

I seemed to have missed this when it was first posted. Gregg, there may be some more interesting Knutsenage lurking in Methodist church archives, esp. in the PNW and CA. You have some photos in the archive from other Methodist camps, no? I would also suggest doing more research in local newspaper archives, especially if the original owner was “a player of note”. Might there be any Foursquare connections as well?

Now I’m curious to know what it’s like to play a harp guitar with the trebles going high to low… I don’t believe any modern makers have done this.