As you know, I thoroughly enjoy researching harp guitar history, and never more so than when there is provenance. Such as this recently discovered instrument.

While we may be missing that one piece of direct proof, it is quite likely that Joe was the original purchaser of this Dyer type 1 harp guitar, Style 5, Serial number 125.

I’ll get back to Joe and his descendants in a moment, but first I want to discuss this rare, beautifully preserved instrument.

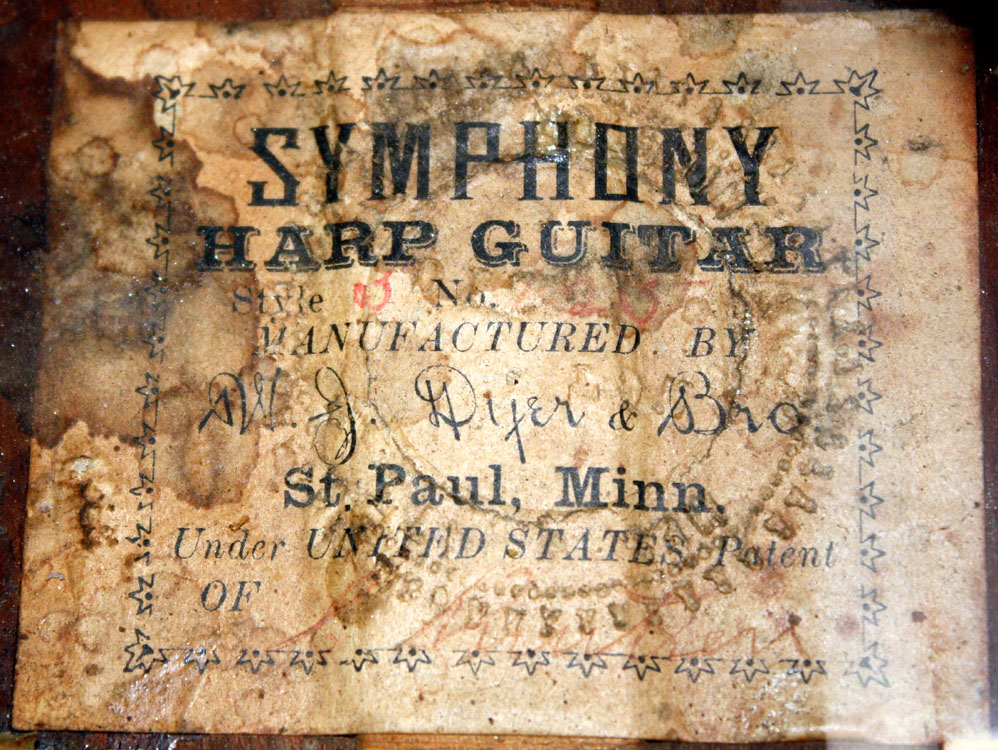

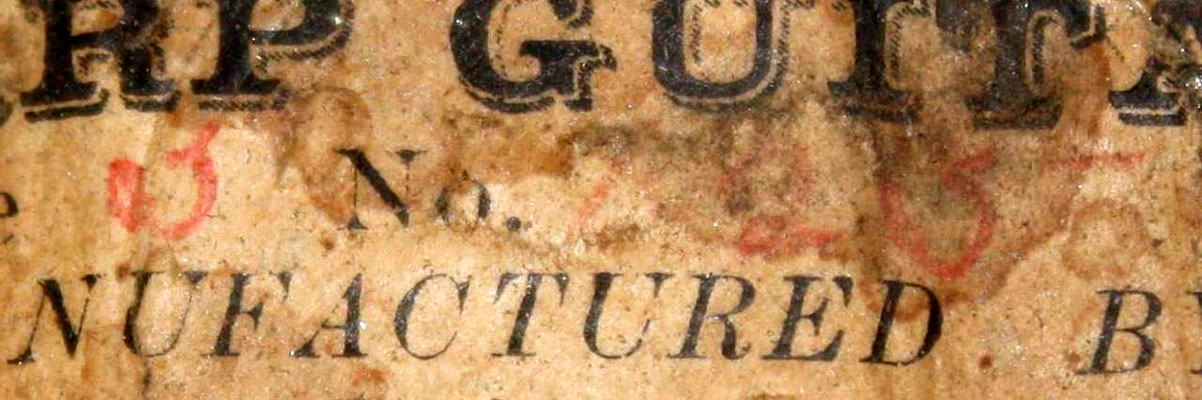

The serial number is hard to read in the photos, but, inspected under various lighting conditions (including black light), the owners confirm it as “125.” That makes it the oldest confirmed Dyer known − what we theorize would have been the 25th instrument built (101 being the hypothetical first). It is also the first type 1 with a decent enough label that we can confidently read the Style number.

Lo and behold, it denotes it as a Style 5 − not quite what we were expecting, but of course, valuable information! (yes, I know it looks like a “3”, but that is because the long, separate upper slash of the “5” − easily discernible on the serial number – is faintly penciled over the dark print underneath).

Dyer aficionados will of course notice that the instrument has no top binding, which all the common type 2 Dyer Style 5’s are adorned with. It matches instead the eventual basic Style 4, though only has 3 dot markers and slightly different rosettes.

As in my theorizing in “Dyer Dating,” what it tells us is that neither the Larsons nor the Dyer Company “knew” that they would be coming out later with the type 2 model, and so they did not set out to assign Style numbers based on body shapes (as, curiously, they would later do for the type 3 – labeled, by complete coincidence, “Style 3”). No, it seems that someone came up with “Style” numbers to denote level of appointments from the very first “Knutsen-copy” type 1 instrument built. My guess is that, for whatever reason, they originally chose “5” for their basic model. We also see consistency, in that the other extant type 1 with the serial number “127” is also marked “Style 5.” Yes! This was one of those aggravating “mystery clues” plaguing the whole Dyer Dating study (which I must once again frantically update!): the only other type 1 label had an illegible mark penciled in after “Style.” But now in comparing the labels of #127 with the newly-found #125, we can easily see that what looked something like a “U” or a zero in #127 is really the lower loop of the unusual (but consistent) hand-written number “5” – the remainder again being faint and masked by the print it was written over. That Style 5 conforms to the new #125 as the plain model. As the remaining two known type 1 specimens match the later Style 7 appointments (I have only seen one of them), it again points to consistency and style designations – were we able to read those labels, they would likely bear the same Style number (perhaps “7,” perhaps something else). This simple information is something Bob Hartman (Larson descendant and author) and I have been after for years.

Compared to a c.1900 Knutsen Symphony harp guitar, this type 1 Larson/Dyer is of similar size: a lower bout of 15-1/2”, scale of 25-5/16”, and 4-1/2” deep at the tail block (most type 2 Dyers are about 4”). The two headstocks are painted black on the front (original). Other than normal playing wear, and a large repaired side crack, the instrument appears in remarkably good shape, considering it was probably tuned up and played for a dozen years, often outdoors in the damp northwest town of Shelton, WA.

Compared to a c.1900 Knutsen Symphony harp guitar, this type 1 Larson/Dyer is of similar size: a lower bout of 15-1/2”, scale of 25-5/16”, and 4-1/2” deep at the tail block (most type 2 Dyers are about 4”). The two headstocks are painted black on the front (original). Other than normal playing wear, and a large repaired side crack, the instrument appears in remarkably good shape, considering it was probably tuned up and played for a dozen years, often outdoors in the damp northwest town of Shelton, WA.

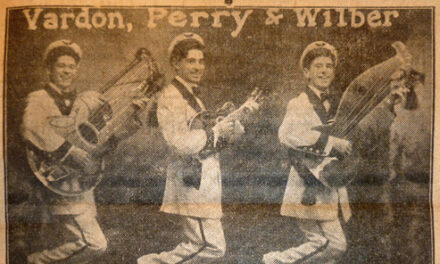

Perhaps, ironically, it might not have survived so well if its “career” had not been cut tragically short like the life of its owner, Joseph Stertz. Joe was foreman of “Camp 5” of Simpson’s Logging Company. In 1915, at 41 years old, he, along with 3 other employees, was killed by a disgruntled former employee (Story here). Up until that fateful incident, Joe appears to have lived a rich life, as the following family photos attest.

Joe (center, with 6-string guitar) in 1904, as yet unmarried

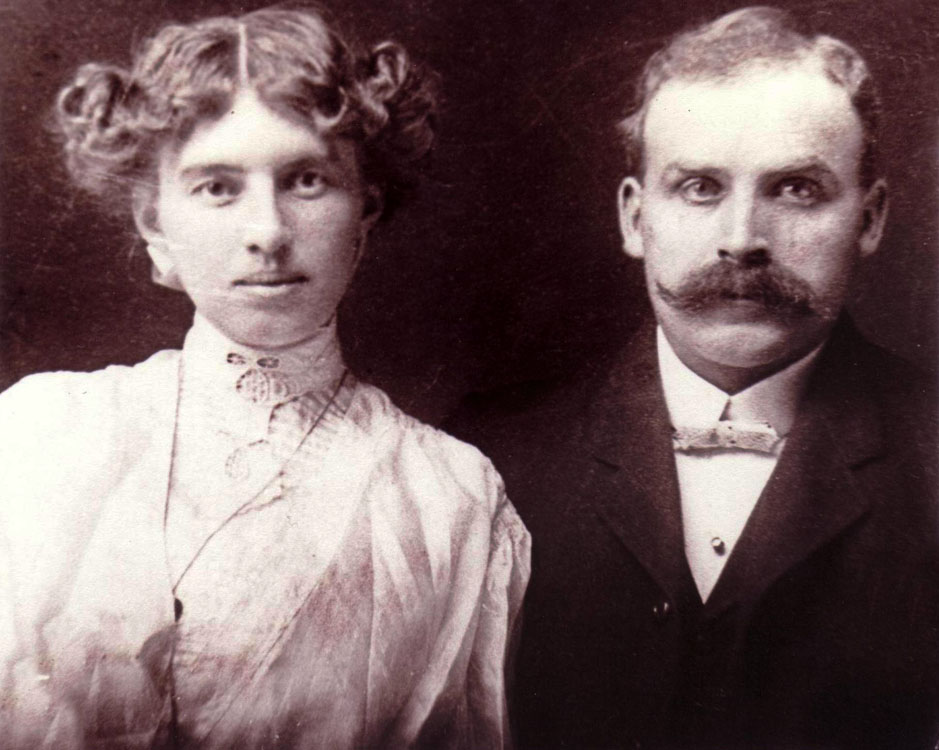

Joe, with his bride, Louise Renz, possibly their wedding photo (married Aug 2, 1905)

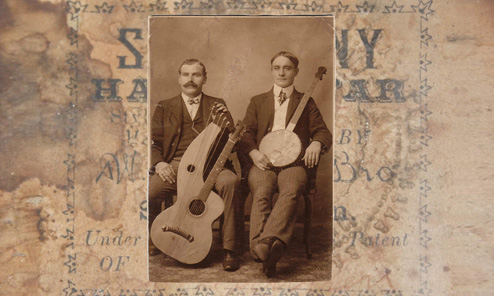

A handsome studio portrait of Joe with his Dyer and banjo-playing companion, c.1906.

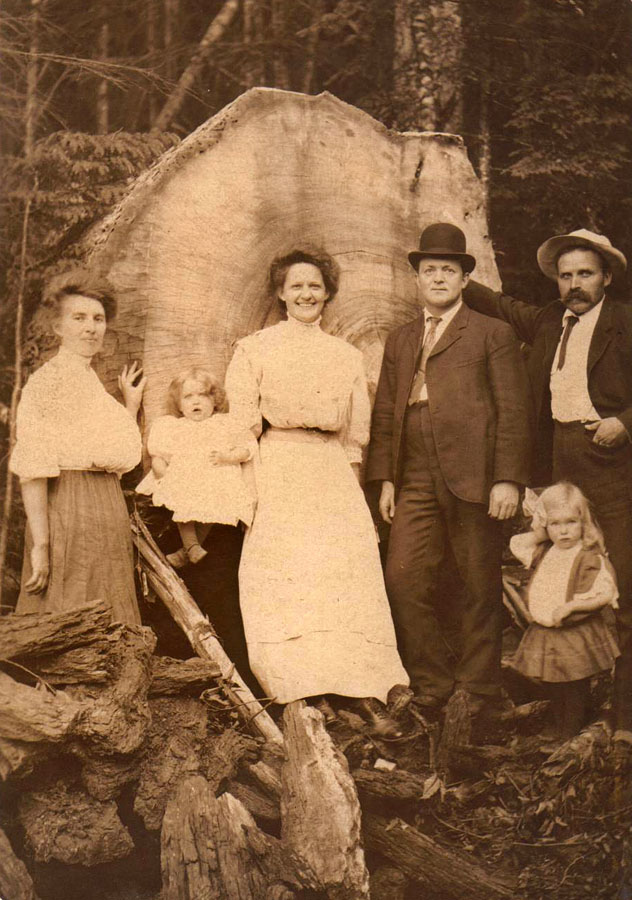

The family with the banjo-playing friend, c.1909

Louise hanging clothes, with daughters Mabel and Lucile, summer of 1910 at Camp 5 in Washington

Foreman Joe on horse at Camp 5, December 1911

(that’s quite a stump, and how’d they get the horse up there?)

Joe (with harp guitar) and fellow musicians, December 1911

Camp 5 workers on push car, with wrapped instruments (date unknown)

Joe is third from left, with his right hand holding what might be the cello seen in the previous image? It doesn’t appear to be the harp guitar – though the family imagines that all the inclement weather, exemplified in this photo, explains the water damage on the harp guitar’s label. Luckily for us, Joe kept it safe enough all those years so that it is still perfectly legible, Knutsen signature and all!

The Stertz family, c. February 1913

The newest addition was also named Joe. He would inherit the harp guitar and keep it safe for four decades in Phoenix.

Robert Workman, grandson of Joe Stertz, via Joe’s daughter Lucile (the middle child), the current custodian of the family heirloom (he received it after the death of his uncle Joe about 1990).

Bob is who first contacted me about the instrument and continues to engage the family – especially son Paul – in further investigation and my own queries.

Back to the instrument. What interests us most specifically about this type 1 is the dating provenance and any other historical clues it might provide. Unfortunately, the family doesn’t know any details of how Joe acquired it. Details provided by Bob Workman’s wife Carol provides the following timeline:

“Joe Stertz was 23 years old when he moved from Donnellson, Iowa to Shelton, Washington in 1897. He left Louise E. Renz in Donnellson to care for her mother. At the time Louise was eighteen years old. Eight years later Joe briefly returned to Donnellson and they were married on August 2, 1905. She was 25 years old and he was 31 years old.”

It seems he had originally proposed to his future wife in 1897, but as she stayed home to care for her mother, the marriage wasn’t possible until 1905, when her mother passed away. Hmmm…1897 to 1905 – 8 years when Joe was in Washington – which was Knutsen country – and covering the theorized years (1902-1904) that a #125 Larson-built Dyer harp guitar might have been built (and sold by Dyer, but presumably not available in Washington). So where did he get it? And when?

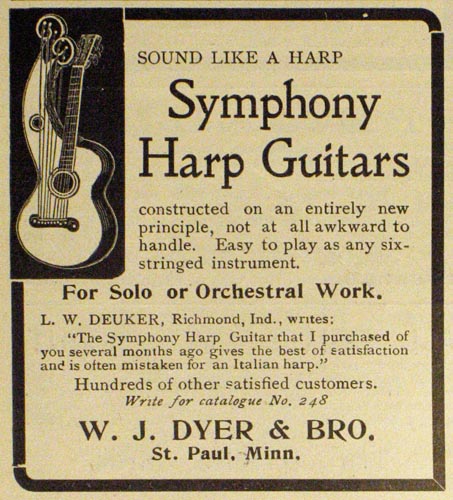

As to where, it is highly unlikely that he found it in Washington, which was Knutsen’s territory. First, remember the c.1899 Knutsen/Dyer flyer that blocked Dyer from distributing Knutsen’s instruments in Washington and California:

I strongly suspect that Knutsen would have been given similar terms that excluded the Larson-built Dyer from being available in the Northwest – though presumably, one could have ordered one directly from the Dyer company in response to the ads that they ran repeatedly in the Cadenza and other music magazines. Joe doesn’t strike me as a Cadenza subscriber (it was fairly “high brow”), but he certainly could have ordered an instrument while in Shelton.

But the simple answer might be more direct: the huge Dyer store in St. Paul, Minnesota. The family is certain that during these eight years, Joe occasionally made the trip back to Donnellson to visit his sweetheart – though these trip dates are unknown. He certainly would have traveled by train (after all, he was a train man himself), and the best of the only two possible routes would have taken him through St. Paul, where he likely would have had long layovers.

Why not take a carriage ride over to the famous music store (or walk – the store was only 6 blocks from Union Depot)? Joe was known to have been a musician – and probably a good one – by 1897 when he left for Washington. His obituary mentioned that during his early logging camp years “he was popular among the young people and in demand with his violin for neighborhood dances.” We also see him with the 6-string guitar in the 1904 cabin photo. Being a musician, it’s not hard to believe that Joe was familiar with W. J. Dyer & Bro. – the largest music establishment west of the Mississippi.

There is also the possibility that he found the Dyer closer to Donnellson, Iowa – say, in nearby Keokuk, in some music store that carried their instruments. Or even that he bought it somewhere second-hand. But my money is on brand new and from the Dyer store.

Regardless of speculation as to the “where,” I’m really more interested in when. After all, this is our oldest confirmed Dyer serial number!

The reality is that, with occasional visits to his sweetheart during their 8-year separation (hypothetically through St. Paul), Joe could have bought the new instrument at any time within our already-existing dating timeline. As you might remember from my long-winded Dyer Dating article, I have 3 possible theories for determining when Dyer sold the first Larson-built harp guitar (the theoretical type 1, #101). Depending on which theory you subscribe to (Larson descendent Bob Hartman is inclined to earlier, I am inclined to later) the options put Joe Stertz’ #125 in either 1902, 1903, or 1904 – but which?! We’re no closer than we were before discovering this latest labeled instrument.

Can the Stertz family photos possibly help narrow the window? Let’s try.

The family can accurately date the photo of Joe sitting in the cabin to December 1904. Does the 6-string guitar in his lap mean that he didn’t yet have the harp guitar? Unfortunately, no, it doesn’t prove anything, though it is interesting in its absence.

The studio photo above showing him with his (brand new?) Dyer is undated, but through a detailed exercise of complicated cross-referencing (including study of his rings, the age appearance of he and his friend, seen in this photo and also later, along with more easily datable ages of the children in the photos) the family deduces that the photo must have been taken shortly after Joe’s August 1905 marriage, but well before 1909.

Remember that we have no firm dates (years) of when he might have traveled back to Iowa – we only know that he definitely made the trip around August 1905 to marry Louise and bring her back to Shelton, WA. Could he have bought a new serial # 125 Dyer during that trip?

I don’t know – 1905 doesn’t seem to be too much of a stretch beyond my previously-theorized 1904…except for one problem. We now know that the well-known type 2 (with the “cloud” headstock) debuted in a Cadenza ad in December 1904; ergo, it was first built by late 1904:

There could have been some overlap with the type 1, but I tend to doubt it. It’s much more likely that type 1 specimens 125 and 127 represent the very last examples of their kind; so theoretically, they would have been shipped out in mid-1904 at the very latest. Of course, it’s not at all impossible that they sat around in the Dyer showroom for a year or more after being built and shipped. Still – remember that an earlier trip by Joe Stertz through St. Paul would fit any of the existing Dating Timelines. And so, back to square one!

Besides myself, the Workman family and other relatives have all commented on the obvious (as you the reader have perhaps already considered): Did Joe ever meet his nearby neighbor Chris Knutsen? Shelton is 30 miles west of Tacoma, where Knutsen was from 1900-1906. From 1906-1913, Knutsen was in Seattle. Both are cities that Joe would’ve passed through on his trips from Shelton to Iowa and back. Yes, it’s certainly easy to imagine Joe coming across a Knutsen harp guitar – especially as we’ve seen photos of other Knutsen-playing logging men! So yes, it is certainly curious that Joe ended up with the Dyer rather than a comparable Knutsen (unless he was a true connoisseur of quality).

Back to the present:

The harp guitar must have been special to Joe Stertz. His widow stayed for a time in Shelton, but when she eventually moved back to Iowa, she took the Dyer with her – which was fortuitous for us, as her remaining household belongings, which she had left behind in temporary storage, were all destroyed in a forest fire.

Bob Workman, the instrument’s proud custodian who lives in Nebraska, tells how “the guitar was housed at my Uncle’s place in Phoenix for decades, and upon his death was given to me about 1990.” After a guitar player friend recently convinced Bob to have the instrument restored, their renewed interest soon led them to Harpguitars.net. After my enthusiastic response, Bob’s son Paul also then commenced to investigate their treasure on the Internet.

Paul Workman and son (and future Dyer owner) Pierce – Joe’s 4th and 5th generation.

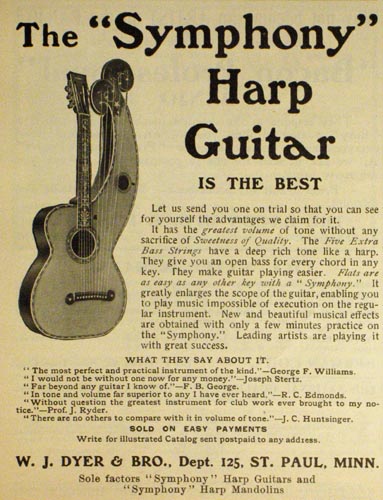

And what should Paul’s eagle eye quickly discover? That his great grand-dad was quoted in one of the famed Cadenza ads!

Does it provide another dating clue? Sadly, no. Joes’ quote is one of several used in the new ad that appeared in the Dec 1908 issue (above; the “backward Dyer” ad that was corrected in the next issue), and ran until April 1910 (you can find the whole run on our Members Only page, “Dyers in the BMG Magazines”). This only tells us that he had the Dyer by the end of 1908, which we already surmised. Neither does his quote shed any light: “I would not be without one now for any money”. The glowing testimonial doesn’t prove that he bought it from them – he could have bought it after-market and just felt compelled to write the manufacturer. Though, personally, I am more prone to imagining the proud owner of a brand new instrument being inspired to sit down and write the “maker,” rather than someone similarly appreciative who just got it second-hand. Again, it’s not a stretch to imagine a Fall, 1905 purchase, with a letter to Dyer within a year or so, incorporated in a late 1908 advertisement (together with several quotes the Dyer company had been collecting…they obviously didn’t all come in at the same time just prior to the ad).

In the end, we are still no closer to accurately dating these most famous and popular of vintage harp guitars. And frankly, other than to a handful of harp guitar geeks like myself, how much does it really matter? The instruments themselves – and their rare, personal stories, when we can get them – are much more significant.

Bob’s wife, Carol Workman, concludes her summary from above:

“(When) Joe was killed at Camp 5 outside Shelton Washington on April 2, 1915, they had been married almost ten years. She was 35 years old and he was 41. Louise later returned to Iowa. Her household belongings, which were being stored in Washington, were destroyed in a forest fire. Now having no reason to return to Washington, she settled in Keokuk, Iowa where she raised her three children Mabel, Lucile, and Joe. The love letters they exchanged during their courtship were torn up after his death and sewn into a pillowcase that she kept until her death. Louise never remarried and lived to be 93 years old.”

Though Joe Stertz’s life was cut tragically short, his memory lives on through his extended family…and his cherished harp guitar.

My Grandfather Joseph V. Burke was also shot at the same incident near Camp 5, Shelton Wa. He was the only one to survive the incident. I believe he and Joe Stertz were probably friends since they were both from the Keokuk area of Iowa. I have the original front page of the newspaper from the Mason County Journal which describes the entire incident and has a picture of Joe Stertz as well as the others killed in the incident. My father, his brother and their mother lived at the camp at the time of the shooting and I have at least one picture from the camps from about 1916 after the incident. I wonder if you or any of the relatives of Joe Stertz might have additional photos or information about this incident. I would be very happy to correspond with them. I grew up in Tacoma Wa but now live in Grants Pass Oregon. I have done extensive geneology work and love the stories that you have shared here. thank you, Kathy Burke

i was so happy to read about my grandpal and all about his guitar i know he was awonderful man and i know i will see him in heaven some day

Thanks for this wonderful post on our family heirloom! Who would have known that the strange guitar that sat in our parlor for 21 years was such a historically significant instrument! I’m happy that you’ve been able to resolve some questions about your reasearch, but I will say for me having learned so much about my family history is priceless…and I will continue to research for the benefit of us both and every Larson/Knutsen/Dyer harp guitar owner/fan out there as well! I bet you can’t wait to get my next e-mail! Ha!

Paul

I have played this guitar a bit, It has a wonderful full sound & is an easy player. The Luthier who repaired it (London’s of Lincoln Nebraska) & all the great area players who hang out there, were amazed by the full tone.

thanx

Doug

Thank you for the wonderful tribute to my grandfather, Joe Stertz. Your account of his short life has been well done and brings back to us many fond memories and stories of Joe and his harp guitar.

Until your website was discovered, little did we as a family know of the significance of this beautiful and unique instrument. What a great service you provide in preserving the history of the Knutsen Larson/Dyer harp guitars.

Sincerely,

Bob Workman,

Grandson of Joe Stertz