There was a boy…

You all know the song − do you know the story behind it, or even who wrote it?

I admit I was clueless, and am frankly surprised I never thought about it until now, despite it being right up my alley – and with, yes, even a round-about Knutsen connection.

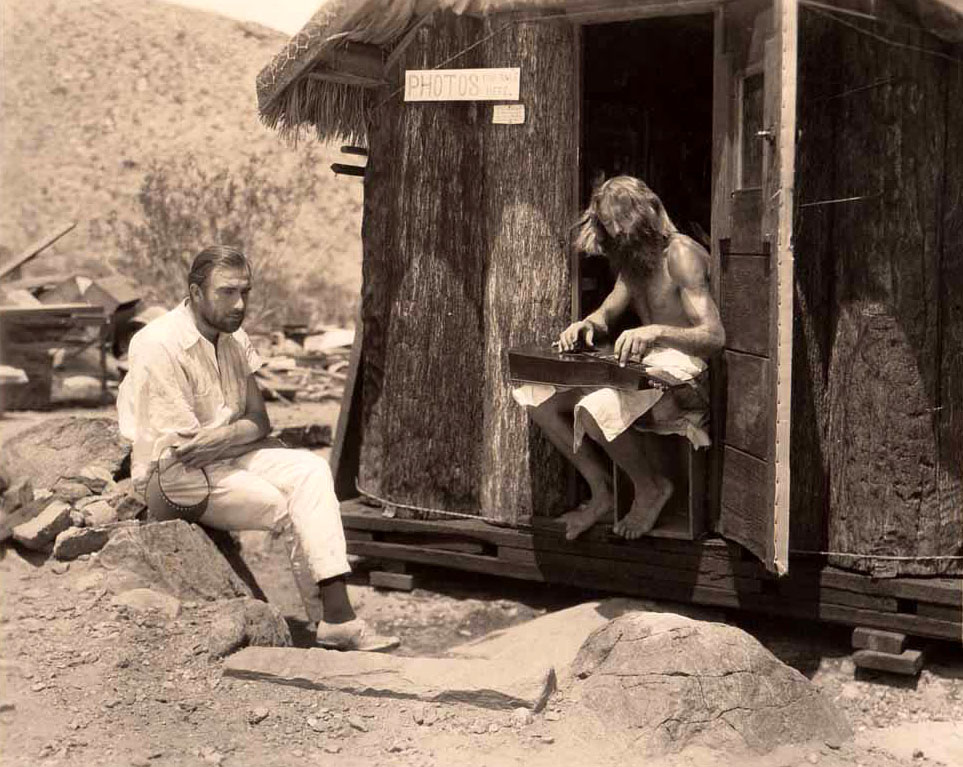

Several weeks ago, I included the newly-discovered photo above in my blog on historical Knutsen players. By the way, it turns out that the long-haired fellow I had been calling “Peter Pester” since the beginning of the Knutsen Archives was in fact William (or “Bill”) Pester. Apparently, he was sometimes incorrectly referred to as “Peter Pester” due to confusion with a similar character of the 1920s & 30s, “Peter the Hermit” of Hollywood.

Hoping simply to identify the man visiting Pester at his hut in Palm Canyon (surely he must be some silent film star or other celebrity), I forwarded the image to my wife’s archivist friends at Paramount Studios. No one recognized him, but one colleague, Bruce Miyagishima, immediately mistook Pester for eden ahbez.

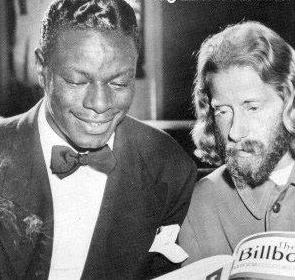

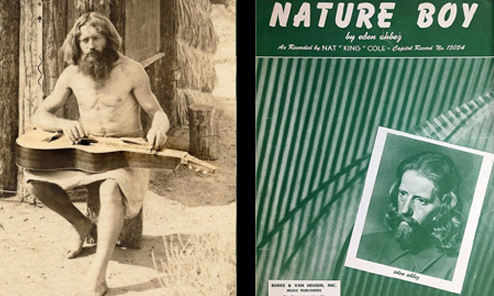

Huh? Who is “eden ahbez”? (and why is his name not capitalized?) Some of you probably know; I admit I did not. He’s the (legendary, it turns out) writer of the 7-week number 1 hit of 1948, “Nature Boy.”

Our friend Bruce is a big Nat King Cole fan, and so knew much of the back story of the strange haunting tune that Nat made famous (and similarly made Cole famous). Bruce sent me links to several online sources that have investigated ahbez, who, in the 1940’s, was one of the California “Nature Boys (think “early hippies”).

Much of the story can be gleaned from the Internet writings of Gordon Kennedy, who wrote “Children of the Sun,” a book that “chronicles the emergence of primitivism, naturopathic medicine and eco consciousness as it traveled from 19th Century Germany to the West Coast of the United States between WWI and WWII.”

After spending a fair amount of time investigating the topic, I thought I had the makings of a pretty interesting blog. Namely, one that asks the fascinating question: Could Knutsen Hawaiian guitar-playing William Pester be the “Nature Boy” eden abhez wrote of in the famous song?

The possibility of that little historical happenstance was simply too good to pass up!

So the research continued. Frustratingly, lack of real details in addition to discrepancies in the timeline was nagging at me; something was just not adding up. I found that there are still many gaping holes (missing years) in ahbez’s life, differing stories about some of the key events, and as much myth as truth about him. At some point (now or later) you should access some of the links I did to learn something of the remarkable ahbez and his unique song (personally, I was, and remain, captivated by it, as it seems so highly distinctive and unusual for a 1940’s pop song).

Links:

Hippie Roots & the Perennial Subculture (web article by Gordon Kennedy & Kody Ryan; if you can’t read Kennedy’s book, this is the next best thing.)

Brian Chidester’s edan ahbez blog (Brian has been working on a biography of ahbez. He is the expert. His blogs are all on one page, oldest at bottom.)

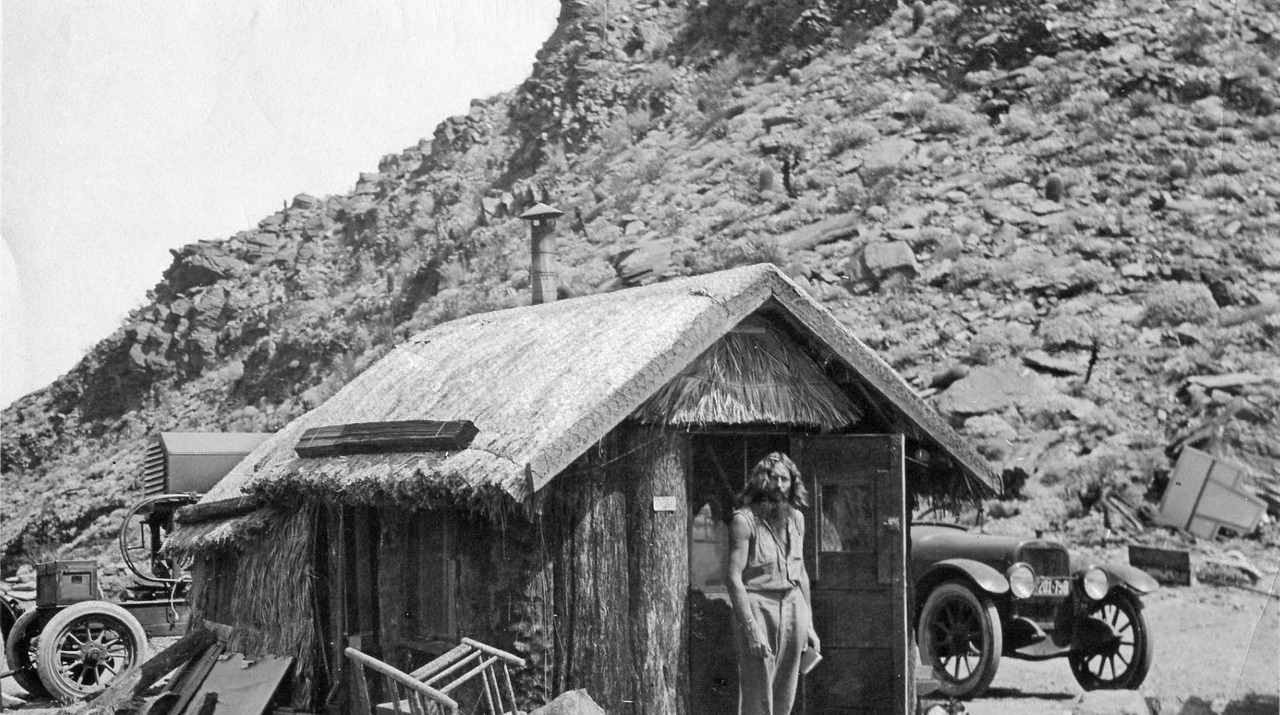

Even less is known about Pester, the “Hermit of Palm Springs” (at left, c.1917). I first learned of him via Ben Elder, my Weissenborn-obsessed pal who first pointed me to photos of Pester with his mystery steel guitar in 2002 (this, or rather, these, instruments will be the subject of Part 2 of this blog).

I soon discovered that Kennedy had a brief section in his book devoted to Pester and, unbelievably, there was a recent entire book about Pester, William Pester: the Hermit of Palm Springs. Both books are out of print rarities (selling for impressive prices no self-respecting hippie could afford), but I was lucky enough to obtain a copy of the former directly from Gordon Kennedy and the latter from the Los Angeles Public Library. As for the Pester book, the author, Peter Wild, passed away soon after publishing it in 2008, so sadly, can’t be interviewed about it. While fascinating and amazingly helpful, it is similarly frustrating in its paucity of clues and facts – and this despite being painstakingly and exhaustively researched. More to the point, there remains an unresolved and wide (and firm) difference of opinion regarding many topics between researchers Kennedy and Wild, uncompromisingly displayed in their books and detailed comments about each others’ viewpoints. You’d have to read the Pester book for Wild’s side of the story; you can see Kennedy’s issues on his Amazon review of Wild’s book. More (my take) on this below.

Back to the tease and premise of the blog: Kennedy suggests (or believes?) that Pester, as the “mentor” of ahbez, was the inspiration for the “nature boy” of the song. Obviously, I’d love to believe that (I even had a harp guitar tie-in all ready to go: Pester’s Knutsen guitar > the Knutsen/Dyer connection > Dyer harp guitar player Stephen Bennett releasing a new instrumental version (played on his modern Wingert) of “Nature Boy” [a hauntingly dark, dramatic and essential version on Cool Tunes for Harp Guitar]).

But after exhaustive analysis of all of Kennedy’s and Wild’s evidence – or more accurately, their interpretations of the extremely scant evidence – I highly doubt that ahbez ever even met Pester. Total lack of evidence notwithstanding (just because we don’t have evidence for it doesn’t rule out a hypothesized event from having happened), the timeline simply doesn’t allow for them meeting in Tahquitz Canyon (or at least not meeting before ahbez penned “Nature Boy”).

Speaking of timelines, it’s time we learned something of Bill Pester.

Where to begin?

In Germany, it seems, where around the turn-of-the-last-century, the naturmenschen arose – “men who rejected industrialization and the unnatural trends of urbanization and who adopted a ‘back to nature’ creed.” Various communes soon appeared, the members embracing then-shocking pagan concepts such as pacifism, vegetarianism, homeopathy, eco consciousness, and of course, optional clothing.

At first (and superficial) glance, one could easily view these men (and women) as the first “hippies.” As it turns out, “Children of the Sun” author Gordon Kennedy has indeed shown a link from Germany to southern California to the ‘60s hippie culture (and thus to many of us ex-long-haired rock and rollers who emulated the “peace-love-dope” mantra of our musical heroes, albeit from the comfort of our parents’ suburban basements and garages).

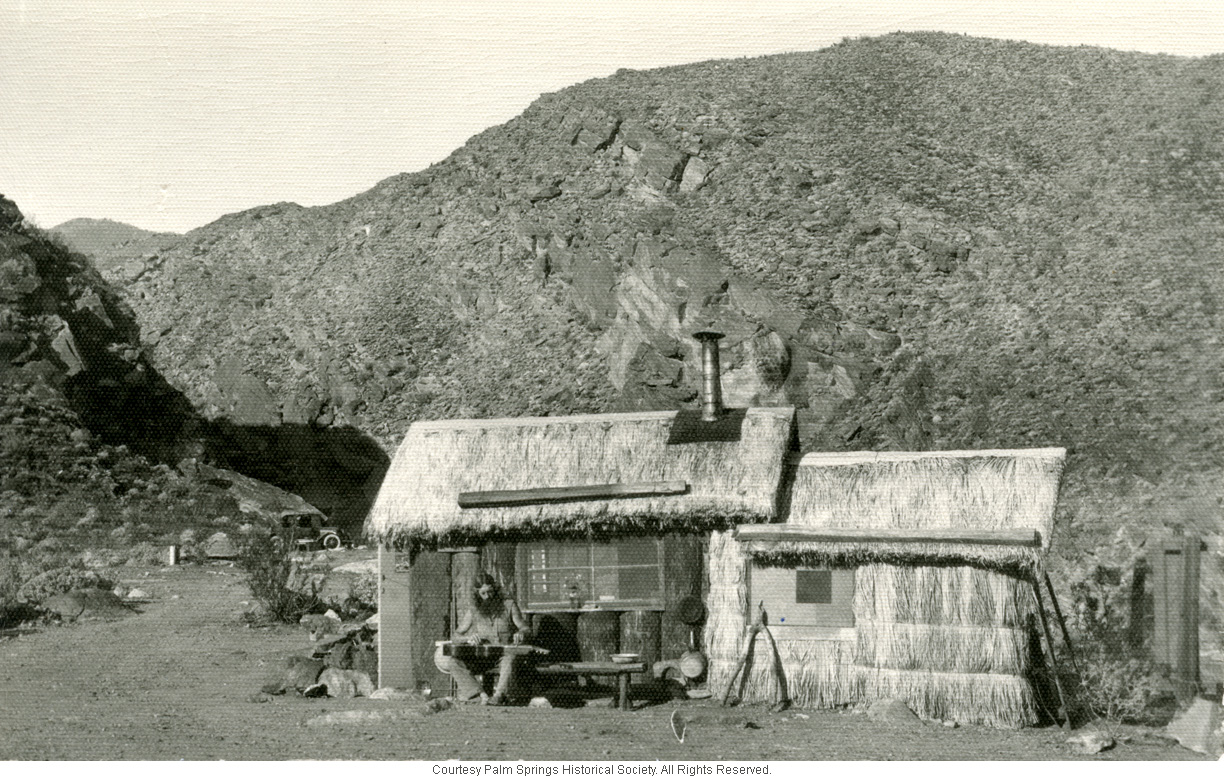

How direct the link is will depend on what you take away from Kennedy’s, then Wild’s, views in their respective books, but the potential link of immediate interest is 21-year-old Friedrich Wilhelm Pester of Saxony (Wild provides his true birthdate of July 18th, 1885), who left Germany in 1906 to avoid the military. Perhaps due to the “hugely popular fictional books about America’s Native Americans by Karl May that every young German of Pester’s generation read” (Kennedy), the bearded, long-haired young man ended up in just such a place of “magic lands in the far west of America, where cactus grew and massive mountains emptied their streams into some palm oasis in the sandy deserts, along with the obligatory wild Indians still in residence.” This was the “majestic Palm Canyon area near Palm Springs, California, then home to the Cahuilla Indians, where Pester would build himself a palm hut by the flowing stream and palm grove.” The debate about whether Pester was “loved” or only tolerated by the local Indians will undoubtedly continue.

Kennedy describes this period: “Bill spent his time exploring the desert canyons, caves and waterfalls, but was also an avid reader and writer. He earned some of his living making walking sticks from palm blossom stalks, selling postcards with lebensreform health tips, and charging people 10 cents to look through his telescope while he gave lectures on astronomy. He made his own sandals, had a wonderful collection of Indian pottery and artifacts, played slide guitar, lived on raw fruits and vegetables and managed to spend most of his time naked under the California sunshine.” Wild describes similar activities, but also puts them (and many others) in much better perspective (even if sometimes speculative).

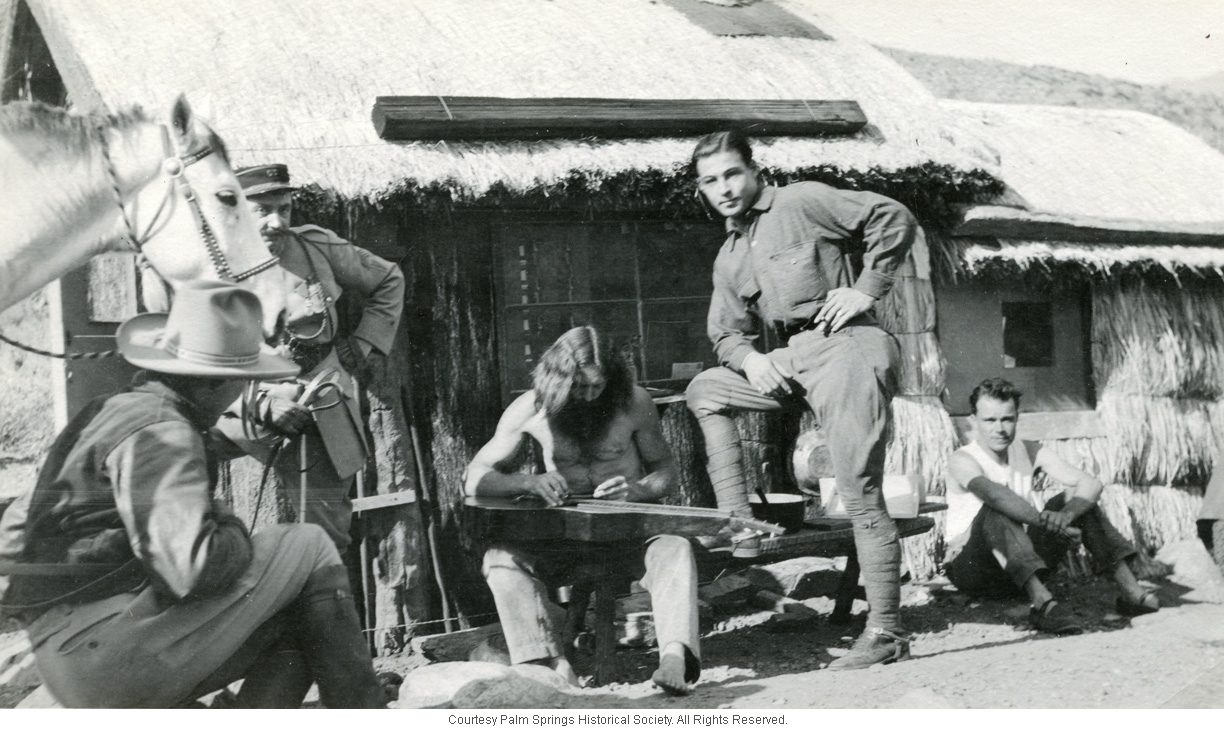

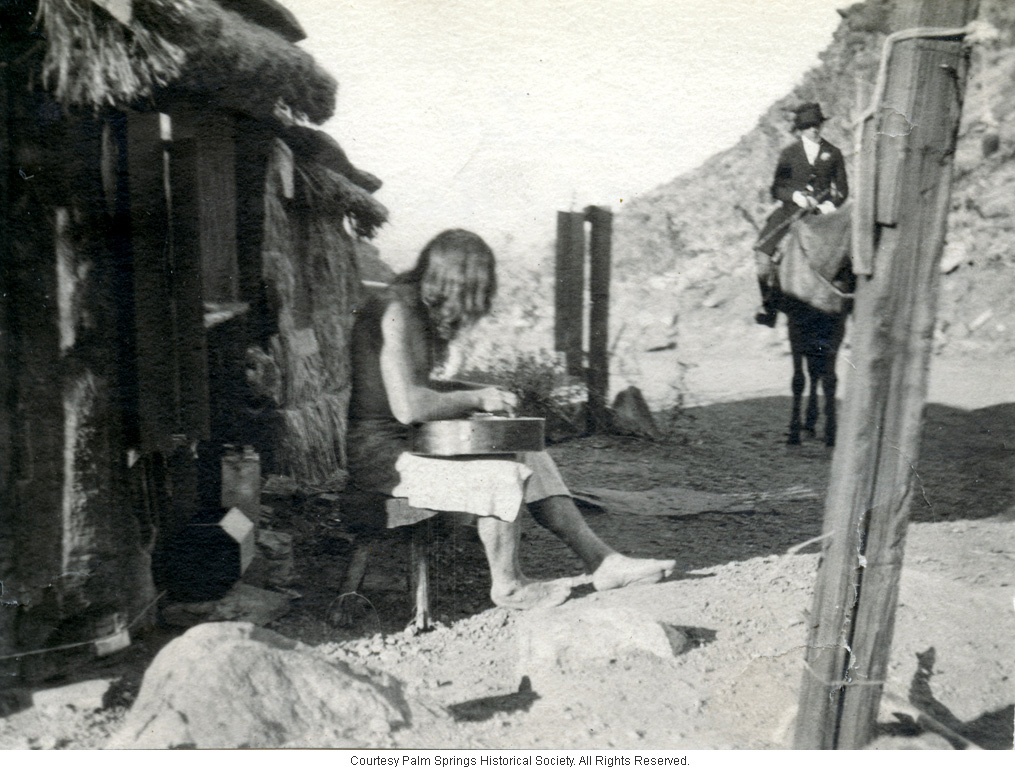

I had known that Pester had plenty of “curiosity value” and was occasionally visited by local celebrities, such as Zane Grey and Rudolph Valentino (seen above visiting Pester while filming in the area c.1920). But I didn’t really know just how much of a celebrity he became himself, made clearer in Wild’s book. Pester grew from a local curiosity to what sounds like something of a destination spot for vacationers. Wild described how, on weekends, “tourists by the hundreds parked their tin lizzies along the sandy road into Palm Canyon” to visit the “hermit turned showman.” (seen below in March, 1927)

This was first during his (mostly) fulltime residency from c.1916-1922 (he was in and out of the desert before then), and again later during the 1927-1940 period when he lived on his own land in Indio, returning on weekends to his old Palm Canyon haunts to earn a few coins from the tourists (how frequently or for what portion of those thirteen years is not known).

Visitors arrived by car (above) and horseback (below)

Interestingly, the majority of surviving photos show Pester playing a steel guitar, one of which I long ago identified almost certainly as a Knutsen. I’ll be going over these photographs in detail with several new Pester surprises in Part 2.

The best shot of Pester’s handbuilt desert home I’ve seen, never before published!

Wild summed up Pester as a “mercurial, myth-generating wanderer, who gave reporters conflicting tales of his life.” In more colorful language, he described “a short, slim man (Wild discovered that Pester was just a bit over 5’3”), with long hair, almost naked, and with blue eyes full of distance.” He concluded that Pester was probably “gentle and even likeable in his mild way…he hardly was an original thinker but an agreeable, if odd, embodiment of walking clichés.”

Kennedy summed up Pester thusly: “The many photos of Pester clearly reveal the strong link between the 19th century German reformers and the flower children of the 1960’s…long hair and beards, bare feet or sandals, guitars, love of nature, draft dodger, living simple and an aversion to rigid political structure. Undoubtedly Bill Pester introduced a new human type to California and was a mentor for many of the American Nature Boys.”

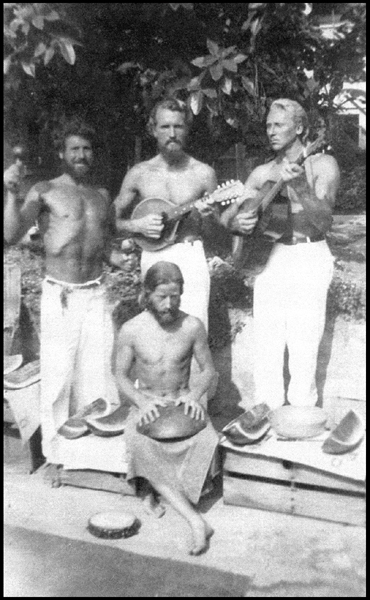

The “California Nature Boys,” as they were soon dubbed, were young Americans who hung out at Eutropheon, a health food store on Laurel Canyon Blvd in Los Angeles, adopting owner John Richter’s “transcendentalist philosophy, wearing long hair and beards and eating only raw fruits and vegetables.” Beat Generation author Jack Kerouac wrote in On the Road that he saw “an occasional Nature Boy saint in beard and sandals” while passing through L.A. in 1947. Soon, one of these “Nature Boys” – eden ahbez – would become quite famous after writing a song based on this name.

(at left, Nature Boys ahbez [sitting], Gypsy Boots [who supplied the rare photo for Kennedy’s book], Bob Wallace, Emile Zimmerman)

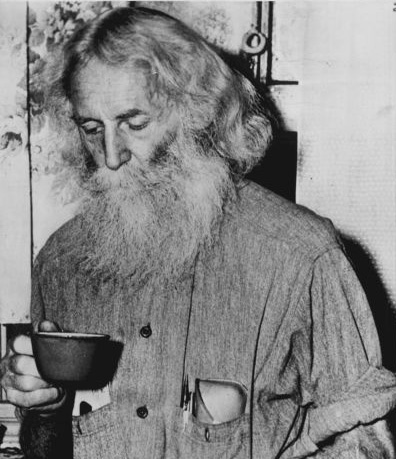

Born (to a poor Jewish family) Alexander Aberle in 1908, he became George McGrew when adopted from a Kansas orphanage, and would eventually have his name legally changed to eden ahbez (pronounced “AH-bee”), deliberately written in all lower case letters, as he considered “only nature and divinity worthy of capitalization.” He was apparently an accomplished musician by the time he reached Los Angeles, with piano lessons, orchestra conducting, and playing in a swing band among some of the stories.

Legend has it that in 1947, Nat King Cole’s valet handed him an unsolicited piece of sheet music from a backstage stranger at a concert. The rest is history, though the details are shrouded in myth (including how ahbez came up with the tune, and who may have helped him plug it around town). Captivated with the haunting melody and mystical lyrics, Cole would soon record it, wherein it shot to #1 on the Billboard charts on May 15, 1948, remaining there for seven weeks. Many other stars would also record the unusual pop song (including Frank Sinatra, below), while ahbez found himself caught up in a media frenzy due to his singular appearance and lifestyle.

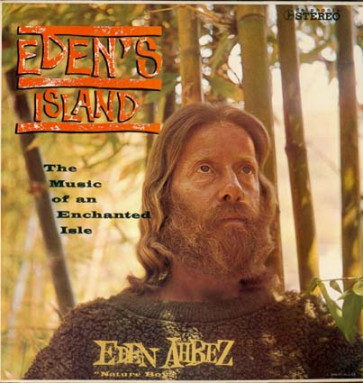

It also made ahbez an in-demand songwriter, and he worked for another three decades in the music biz, creating a followup to Nature Boy for Cole (which flopped), writing songs for white pop singers and prominent black artists alike, and recording one of the first “exotica” albums of instrumental music in 1960 (at left). Eventually, ahbez faded into obscurity and fell off the radar. He passed away on March 4, 1995 from auto accident-related injuries.

What we don’t know is exactly when ahbez arrived in Los Angeles. I’ve seen “around 1941,” “about 1943,” and “sometime in the 1940’s.” No one – Wild and Kennedy included – has really addressed the specifics of the elephant in the room: namely, that Pester was almost certainly gone from the Palm Springs area before ahbez arrived, as he was arrested in the summer of 1940 and sent to San Quentin prison that September.

(Sidebar: No one has yet posted any details of Pester’s criminal charges on the web and I’d rather not be the first. Photocopied transcriptions and other evidence are collected in Wild’s book. I will say it’s interesting how both Kennedy and Wild so casually appear to give Pester full benefit of the doubt, despite his own seeming damning testimony. This may be the bigger “elephant in the room”…).

William Pester in Los Angeles, shortly before his arrest (photo marked Fe 14, 1940)…

William Pester in Los Angeles, shortly before his arrest (photo marked Fe 14, 1940)…

…and in June, 1949, back in the Los Angeles area.

…and in June, 1949, back in the Los Angeles area.

Exactly when Pester was released from prison is unknown − at least not until late 1945, and perhaps by July, 1946 (by which time ahbez had allegedly already written his famous song). I suppose that’s why both authors sort of dance around the issue of a Pester/ahbez meeting, as there are no specifics, only the opinions: extreme likelihood against (in Wild’s case), and seemingly wishful thinking for (in Kennedy’s case). Indeed, Kennedy says flat out in “Hippie Roots & the Perennial Subculture,” co-written with Kody Ryan, that “it was in Tahquitz that ahbez first encountered his mentor, William Pester.” By implication, this would seem to also include all of the California Nature Boys, as the authors describe how “In the 1940’s Boots (Gypsy Boots, a prominent Nature Boy-GM) lived wild in Tahquitz Canyon with all of the Nature Boys, bathing in the cool mountain water, eating fruits and vegetables, sleeping on rocks or in caves, hiking and selling produce in Palm Springs.”

Sounds idyllic, yet there is so far zero actual evidence that any of the Nature Boys ever actually met William Pester in person (which is what so intrigued me and instigated this whole fascinating, frustrating research project in the first place!).

In his book, Wild was quick to point out the discrepancies and unsubstantiated claims, as he was right to; he was a scholar who did his homework. A professor of English at the University of Arizona in Tucson, he was also a poet, and was not adverse to his own speculation and imaginative story-telling. He seemed (to me) to be “firm but fair” (if a bit relentless) to Kennedy in his criticisms and analysis, and even allowed for the possibility of such a meeting, despite the problems with the Pester/ahbez timeline and other interpreted clues. (On a side note, Nicolette Wenzell, Associate Curator and Collections Manager at the Palm Springs Historical Society ― where both Kennedy and Wild did research for their books ― told me that Wild was “the most thorough scholar we have ever had come through here!” His book even cites me: ‘Miner, Gregg “Knutsen Historical Photographs.” An intelligent survey of the development of the Knutsen guitars…’)

Here again, one should carefully compare and weigh the narratives of both Kennedy and Wild, along with any actual evidence.

After pouring over and over the narratives and longing for a tie-breaker, I corresponded briefly with ahbez biographer (and New York Village Voice writer) Brian Chidester. He kindly shared his thoughts, which generally echo Gordon Kennedy’s:

“Every time I find out about another bearded hermit that lived in SoCal, which I trust was effectively isolated from the rest of them, I end up finding some evidence that they knew of each other and often met at one of the rare health/meditation centers that existed from Santa Barbara down to Laguna Beach and out to Palm Springs. They were so rare in the 1930s-50s that it seems rare that they WOULDN’T know of one another.

“Bob Wallace, one of the California Nature Boys, told me that he knew of Pester the time I interviewed him several years back. I asked Wallace if he was their mentor and he said no. However, Wallace was late in coming to the CA Nature Boy fold, having been a dozen years younger than both ahbez and Gypsy Boots and even more years with Buddy Rose and Emil Zimmerman, the latter two who were definitely around when Pester was at the height of his fame (a relative term) in the desert during the 1930s.

“It is without a doubt that Pester…laid the groundwork and gave solid example, if not real-world advice, to those who became known as the California Nature Boys. I’d say it is impossible to imagine the Nature Boys not all having known him.”

I dread having to drag Chidester into the fray, but I remain unconvinced (and there’s quite a gap between “known” and “known of”). Still, his answer is more thoughtful than Kennedy’s, who on his Amazon review of Wild’s book says, “As for the connection between eden ahbez and Bill Pester, when you’ve talked with as many Nature Boys and Reformers as I have, after a while you just get a sense of what leads to whom and why. Nearly everyone I have spoken with has remarked on the similarities between Pester & ahbez…and the fact that both of them had so much to do with Palm Springs.” (Sorry, but not exactly the convincing evidence I was looking for…)

So, did the Nature Boys know about Pester? It would seem pretty obvious that they did. Did any of them meet him in person or spend time with him? That is currently impossible to answer. It sounds like Rose and Zimmerman may have had the opportunity; for ahbez, no opportunity that anyone has yet shown (Chidester currently places ahbez in Kansas in 1932, New York City and Florida in the mid-‘30s, Iowa in 1938, and in Los Angeles by Decemeber, 1941 – but no confirmation of ahbez in Santa Barbara in the ‘30s as described in Kennedy’s book).

Finally, my own observation: The Nature Boys were originally in the L.A./Hollywood area and sometimes sleeping outdoors further west in Topanga Canyon (up the road from my own home) – but then found themselves some hundred-plus miles away in Tahquitz Canyon, which is very near Pester’s original haunts. Was this a pilgrimage to visit the well-known kindred spirit they had heard about (and finding him absent, remaining in the area)? Though knowing little of these men or their lifestyle, this seems to me the simplest provisional answer.

OK, so then the thousand dollar question: the song “Nature Boy”…

Kennedy & Ryan say in their web article that the “song itself was part autobiographical but was also a nod to his German mentor Bill Pester who was 23 years his senior and had been a Nature Boy for decades when eden encountered him in the Coachella Valley of southern California.”

Chidester admitted to me that “Gordon likely overreached in positing Pester’s influence on the writing of ‘Nature Boy.’ Still, Pester laid the groundwork and his effect reached the Nature Boys whether a paper trail certifies it or not. The fact that the last living Nature Boy (Bob Wallace) remembered him as a presence in their world over fifty years after his passing is no small testament to Pester’s lasting influence.”

Wild (in addition to other criticisms mentioned above) brought up the point that, when frequently queried about the origin of his hit song, “nowhere, given all his chances, does eden ahbez mention Pester, something the generous composer likely would have done had Pester been his inspiration.” Though that is just an assumption, it seems a valid one. Wild ends with the more significant fact that ahbez said he wrote the lyrics “four years prior to its recording,” which would have been c.1943-44, when Pester was in jail. Wild suggests that, had the lyrics been about Pester, ahbez “surely would have” mentioned his mentor “languishing in jail.” Again, logically posed (although it strikes me that Wild seemed more interested in drilling holes in Kennedy’s theory than in facing what is to me the bigger question regarding this clue: did ahbez know what Pester was accused and convicted of, and what did he and his fellow Nature Boys think about it? Were they sympathetic? Did they renounce him? Were they oblivious?

Thinking back to the very beginning of this little research adventure of mine, I remember being struck by the how the lyrics could so easily be taken as referring to Pester (the “nature boy” who “wandered far over land and sea”) and ahbez (acting as the song’s narrator, telling of the meeting). An additional candidate some have proposed as inspiration for “Nature Boy” is Paramahansa Yogananda, an Indian yogi and guru of southern California. And the list goes on. Of course, it could just as easily have meant to represent ahbez as the nature boy (he was, after all 23 years younger than Pester), with the song’s singer acting as narrator. Or it could simply be “mystical allegory” about his personal lifestyle.

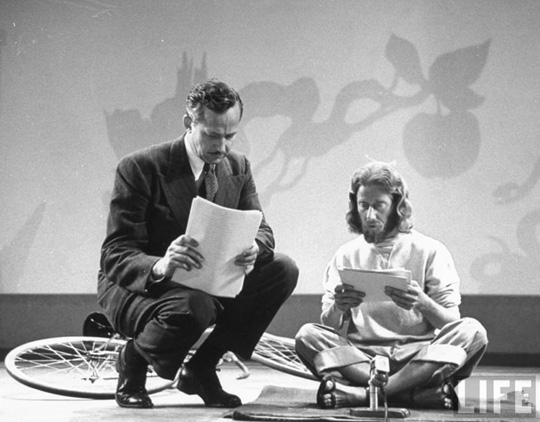

That’s what I took away from his own explanation. Yes, straight from the horse’s mouth is this rare video of a TV appearance of ahbez from 1948.

June, 1948: ahbez on “Meet the People”

June, 1948: ahbez on “Meet the People”

His carefully prepared answer (written and held on camera) − “I guess it’s really about my life” – pretty much sums up this long-winded, no-easy-answers blog, and perhaps all the speculation and discussion about the song. And if William Pester, the Hermit of Palm Springs, was any small part of this life, then I suppose we might consider him at least some fragment of the mysticism of that inscrutable, haunting song.

There was a boy

A very strange enchanted boy

They say he wandered very far

Very far, over land and sea

A little shy and sad of eye

But very wise was he

And then one day, a magic day

He passed my way, and while we spoke

Of many things, fools and kings

This he said to me

“The greatest thing you’ll ever learn

Is just to love and be loved in return”

Special thanks to: Brian Chidester, Gordon Kennedy, Nicolette Wenzell at the Palm Springs Historical Society

PERSONAL NOTE: The huge amount of interest in this article is very rewarding. For Pester/Nature Boy/guitar fans new to my blog and site, may I point out that while you’re getting my time, energy and rare material from my own personal archives for free (with pleasure), many things – including archival material and licensing fees for this article – are not without expense. I am able to fund, obtain and share it through our nonprofit Harp Guitar Foundation, which only survives from tax-deductible donations from passionate readers like you. Here’s the Donations link if you’re so inclined. Thanks for reading! – Gregg (Sir Gregory) Miner

Thanks for your research. Could you tell me who William pester married? Thanks , Len

Hi Sandy,

I’m writing a book about Eden Ahbez currently and would love to talk to you further about your Uncle Emil. My email is bcxists (at) gmail (dot) com. I hope to hear from you soon!

Brian

It’s been a long time since someone made a comment so I’m not sure if this will be seen. I just want to point out that not all of the original Nature Boys were American. One of them, Emil Zimmerman was my Uncle and he was Canadian although he did spend a lot of time in California, as did my Dad on occasion.

Hi Gregg,

Thank you for quoting me accurately, and for criticizing any research or opinions thoughtfully. A few follow-ups, if you don’t mind.

(1) Bob Wallace told me that the Nature Boys spent winters in Taquitz because L.A. got below 50F at night, and the desert region was more tolerable for living outdoors. He said they returned to L.A. — mostly Tujunga and Topanga Canyon — during springs and summers, where the weather was lush and there were lots of fresh veggies and fruits selling at marketplaces, and wild edibles growing on the trees.

(2) It’s true that ahbez never mentioned Pester in any of his comments on “Nature Boy,” the hit song. But, in over 300 photocopies I’ve made of interviews, news clippings, etc. regarding “Nature Boy,” ahbez never once mentions Gypsy Boots either. He never mentions Buddy Rose, Emil Zimmerman, Bob Wallace or ANY of the other California Nature Boys. In fact, he never even mentions that he was part of a loose group of reformers living outdoors. Never. Not that I’ve ever found. So by your logic, ahbez not only never met Pester, but not a single California Nature Boy either, if we go by his never having mentioned them in relation to the song “Nature Boy.” We, of course, know that isn’t true, as there are half a dozen pictures of ahbez with some or all of the known Nature Boys. But for some reason, ahbez wasn’t into sharing the inspiration for that song with his confreres.

(3) “Nature Boy” was, in fact, as you wrote, composed in 1946; possibly sooner. It was, for certain, published in 1946, as there is a sheet music released in ’46 by Goldenheart Press, replete with a hand-drawing of a hobo with gunnysack, walking into the arid desert. Presumably this drawing is by ahbez himself, as the entire sheet music print is decidedly low-brow and hand-made. Of special note, however, is how different the song was in 1946 from its eventual version by Nat King Cole in spring ’48. Most startling is that all of the lyrics are different, accepting the first line, “There was a boy.” (It follows with, “… and they call him Nature Boy,” and rambles endlessly from there.) A lot of people claimed credit for “Nature Boy” when it first hit in 1948. Most of the claims were summarily dismissed, even the ones that made it before a judge. One case was settled — that being an old Yiddish playwright, who penned a similar melody in 1935 titled “Schveig Mein Hartz.” There was, however, one curious article I recently came across, dating from the fall of 1948. Therein a middle-aged woman claims to’ve helped ahbez whip the song into shape from its more unwieldily origins. I would normally doubt her claims if I didn’t know how right she was in describing the first version that way. In other words…

“The quest continues!”

Be well,

Brian

Wow. There is so much research here. I thought I knew a lot about the Nature Boys, but there are so many great tid bits here. I always was told (by Gypsy himself, so…) that the song “Nature Boy” was written about Gypsy Boot, the founder of the “Nature Boys.” Gypsy had the first ever “Health Food Store” and also was the first to call his health drinks “smoothies.” One of the early inspirations for the later hippie movement of free love.

Great article Gregg,

I wrote about the Nature Boys at Reality Sandwich magazine, though it’s a short piece and you’ve included everything I came up with—and more.

https://realitysandwich.com/214803/the-nature-boys/

I think the legacy of the Nature Boys is important, as Kennedy illustrates, that these sorts of subcultures are perennial and the story of 60’s hippies is only one aspect of a broader movement of cultural influencers.

Can’t wait to read part 2!

thanks for this. some photos i have not seen before. this story is an obsession of mine. i was born in oakland in 51 and became a card carrying hippie in 69. the nature boys are my heros and inspiration. i finally got back to the land in 76 and ran food co-ops in michigan until 83. moved to nm in 85 and lived on the edge of the gila wilderness under the stars. now back in mi still living the dream. pls email me when u get the next part finished. although i havent read a lot of wild i agree w gk and feel that wild seems to pander to conventionalism, was natively hostile to the hippie dream and so not a completely fair chronicler. i cant believe there was no contact between pester and the nature boys. it just doesnt make any sense. it was interesting to hear that ahbez considered himself the subject of nature boy but there must have been some connection w pester. its all just too coincidental. i’m glad ur keeping this story alive because it is so relevant to the mess civilization has gotten itself into and can be a beacon for the adventurous and enlightened minds of young people searching for answers. i hope they hear about it. i do my best to spread the word. thanks again and keep me informed.

Fascinating stuff Gregg. Thank you for all of the work it took to put it together. As a fellow blogger for almost four years, I understand the incredible commitment it takes for (in my case, at least) absolutely no remuneration.

Many thanks, David from stargayzing.com

P.S. The comments of your readers are really adding to the narrative, which is almost better than money. (Though you can’t actually eat the engagement of your readers, you can live off it in other ways).

I spent almost every day from 1971-4 with ahbe, and visited him many times between rhen and his death. At the time he kept a simple white house off the beaten path below Foothill Blvd. in Sunland. Buddy Rose was a frequent houseguest, he and ahbe were close friends.

ahbe never mentioned Pestor to me, but among his other stories, he said he wrote Nature Boy about himself, riding the rails to California leaving Kansas. He said he carried it around for years, and gave it to a member of Cole’s band in a club in Hollywood. He spoke of the time he spent with Paramahansa Yogananda, called him a friend.

Later, ahbe spent some time at The Hog Farm in Tujunga Canyon, and it was a woman he met there in the late 60’s named Judith who introduced me to him originally.

ahbe loved the desert, and when he could, made frequent trips to hang out with his old friends around rhe Salton Sea. He was head there again when his van was struck and he was killed.

So interesting, thank you for all of the work you put into this. It is a song I fell in love with in the 50’s and still pleasantly haunts me. How fascinating!

Mike Johnstone here – I’m a musician and studio recording engineer in the Los Angeles area. From 1977 to 1981 I was working for Leon Russell at his studio complex in Burbank called Paradise Records. One day in late 1979 or probably 1980, someone at the office – probably Diane Sullivan – called and assigned me to engineer a recording session with some guy named Auby Abhez. Abhez showed up driving a late model van full of musical instruments including a very large expensive looking Japanese gong. He had long hair, a beard, seemed to be in his 70s and had a large collection of percussion instruments which he brought into Studio C and he and I took several hours to lay them out and set up several stereo pairs of mics. We were booked for two full days in the studio and I had no idea what the game plan was and neither did Abhez it seemed. I asked him if he wanted to work with a click track and he didn’t want anything like that dictating what or how he was going to play. He seemed to just want to chat and tell me little fragments of stories about his life and times as he went around the room shaking shakers and banging on hand drums. Finally I suggested we roll tape and see what happened. He was most interested in the gong so he played that for a couple rolls of tape with no specific pattern or groove. He then moved to the hand drum and he played that for a couple hours. This went on for the whole two days and at the end of the second day I made him 1/4 inch 2-track “mixes” of what he had done and helped him pack up his stuff. He paid his bill at the office next door and he and I went out to a nearby health food joint and had a salad. Then he dropped me back at Paradise and I never saw him again. Of course I’d heard Nature Boy by Nat King Cole all my life but only in the days and weeks following that episode after sharing the experience with Carol Kaye and Leon Russell did I figure out who he actually was and then of course wished I could spend a little more time hanging out with him. My impression was although he was quite intelligent he was a simple, gentle soul who seemed like he had been lifted right out of another place and time. He was certainly a fish out of water in the recording studio although I’m not sure he ever realized that.

Great story, Mike – thanks for sharing!

Thanks to all of you for your kudos and comments.

I can’t say this enough, but I am just so impressed how little it takes to get you started. This tiny bit of trivia and whooosh, there you go; the world is suddenly so much more informed on every tiny little aspect of this otherwise negligible piece of history. It is just so extremely interesting to read and my entire weekend has been transformed. Adding to this: I just saw “King of California” wit Michael Douglas. The entire movie turned out to be about “eden abhez” even if mr. Douglas never heard of him. Gregg; you put color to those stories!

Fascinating article. Thank you.

Reminiscent of Harry Oliver, another artist and art director who settled in the 1000 Palms area in the 40’s. He built an adobe house and started his own little newspaper.

Hi, and thank you! I found this story to be fascinating, only peripherally because of the guitar tie-in. I own a number of guitars and there are several lap steel and resonator guitars in my collection. My fascination lies in the history of “Nature Boys.”

In the early ’80s, I had the occasion to meet a naturemenschen in the Okanagan Valley in British Columbia. Fritz Preusse was a little over 90 when I met him and he embodied the whole “nature boy” aesthetic you describe. Fritz had left his bank managing position in Germany to move to the edenic Valley in B.C. shortly after World War 1. He brought a number of like-minded German ex-pats with him. Together, they formed a communal farm near Kelowna, and over the years, they hived off other farms, where they grew mostly vegetables and fruits. The Okanagan Valley is known for its un_characteristic-for Canada warmth and long growing season. When I visited Fritz he fed me his own produce. I ate freshly-baked brown bread with butter and honey, berries, peaches, pears and apples and goa’s milk cheese, all of which he and his wife had made.

I was struggling with marital problems at the time and, on the referral of the head a local ashram, had been sent to Fritz. He generously offered my wife and me some time to sit and talk. While he took time to counsel with my wife, he suggested I go and find a rock in his garden that I could keep and treasure as an anchor, of sorts, to the natural world. Fritz had run a lapidary business. After he stopped collecting, polishing and selling rocks and minerals at the side of the road he had abandoned his beautifully crafted oak display cases in the yard. Each drawer was stuffed with beautifully polished stones of all descriptions. I chose a piece of petrified wood that was amber and white. Fritz said that I had chosen wisely in that piece, as it combined elements of earth and what grew upon it. About the marriage, sadly, I had not been so wise.

Now, that piece of petrified stone sits in a place of honour in the largest room in the house, the music room/ kitchen. When I look at it, I’ll think about this blog, marriage (I am about to marry the lovely Bluegrass musician, Claire Lynch) and continue to save for a harp guitar, just like the one I have heard Stephen Bennett play many times, both at Swannanoah Gathering and up here in Toronto.

That IS one of my favorite songs. There is nothing else like it. Fascinating back story to it. It was published in the year of my birth. The short interview video was cool but the duet that follows was a surprise gift. Thanks for researching and posting this. It is very special to me.

Michael

Me too. Can’t wait how interesting. thanx

I’ve been singing that song for about 20 years and so was somewhat familiar with the story but not Pester’s.

I have to say that sometimes when I’m singing it there is a feeling that he’s talking about Jesus. Was abhez a Jesus fan at all perhaps even in a not so Christian sense?

Very well done, Gregg. When will part 2 be ready?

Can’t wait for Part 2!

Thanks, Gregg.

sb

Great story, thanks so much for delving into this murky subject! Looking forward to Part 2 – and we DO want to know why Pester went to jail.

Very interesting .. I thoroughly enjoyed the story .. I lived in the Coachella Valley for 38 years & worked in Palm Springs .. It reminded me of a man .. a hermit .. that I passed every morning on my way to work .. I always took a short-cut through the Desert .. very close to Tahquitz Canyon …The man looked a lot like the character in your story.