The current Harp Guitar of the Month – another one-of-a-kind instrument – got me thinking again of Albert Shutt, a truly interesting footnote in the history of Gibson mandolins and guitars (and harp guitars).

Those in the know – which presumably include many early Gibson instrument fanatics – have probably read my original 2008 article on Shutt. There, one will find all the details of Shutt’s patents, inventions and designs, and see how they compare to the Gibson instruments. Of course, I wasn’t the first to point out how Shutt added F-holes to his carved top instruments before Gibson, just one among many other interesting developments that I described then as “a clear reaction to , and competition with, the Gibson company’s popular features.”

(Left: c.1911 Shutt Artist’s Model Style 3, owned by Lowell Levinger / Gibson F4 from Mandolin Archives)

Shutt’s inspiration and reasoning, which we can only speculate on, is undoubtedly far more interesting than simply comparing patent particulars. Though I can’t fully relate to or sufficiently envision that time and place, it’s fun to try to imagine the private scenario (sort of like a docudrama in my head). And what I see is a small-town “David” (Albert Shutt of Topeka, Kansas) intrepidly taking on the juggernaut Gibson Company “Goliath.”

Why? What motivated him to do so?

It recently occurred to me that, as a full-time music teacher and organizer of banjo, mandolin & guitar clubs, it is quite likely that in the beginning Shutt himself may have originally been a Gibson Teacher-Agent.

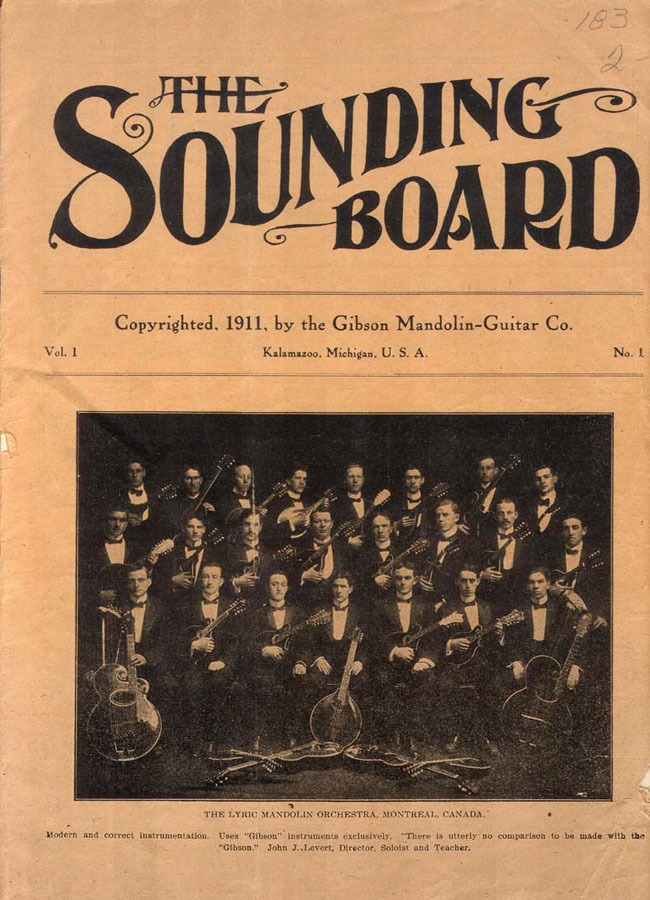

He was exactly the kind of person they beat the bushes to recruit. If he was, Shutt would have been fully in the loop, receiving the annual members-only publication The Sounding Board (left, courtesy of Paul Fox), and making a tidy profit on the sale of Gibson instruments to his students and groups, a business model that succeeded by feeding on itself: more players = more customers = more sales = more players, ad infinitum.

And if Shutt wasn’t a Gibson teacher-agent, I would wonder why not? Perhaps only because the instruments were too expensive for his students’ tastes? Gibson clubs seemed to have succeeded in nearly every other town across America, so that seems unlikely – though might provide a reason for Shutt to brainstorm a way to offer less expensive instruments, a fact he touted in his catalog.

A Shutt mandolin listing at The Music Emporium makes the claim that “often they were sold through independent fretted instrument teachers not involved in the Gibson teacher/agent marketing plan.” Perhaps Shutt tried to emulate their marketing ideas as well as their instrument features?

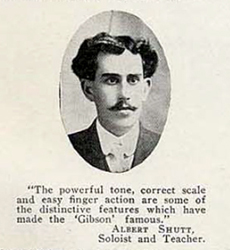

Regardless of the hypothetical scenarios above, it is more than obvious that Shutt was a Gibson fan, one very familiar with their instruments and all their changing models. His one and only appearance in a Gibson catalog (left), #G from 1910, proves this, but only tells us what we already knew – that he was a player and teacher and was familiar with their instruments (ironically, his testimonial appeared even as we was creating and patenting his first mandolin design).

Indeed, his own work focused solely on features related to Gibson design, manufacture and aesthetics. And for whatever reason, he seemed single-mindedly bent on creating his own personal version of their instruments. A few others attempted their own Gibson-inspired carved top mandolins (Bacon and Dayton come to mind), but none so passionately as Albert Shutt.

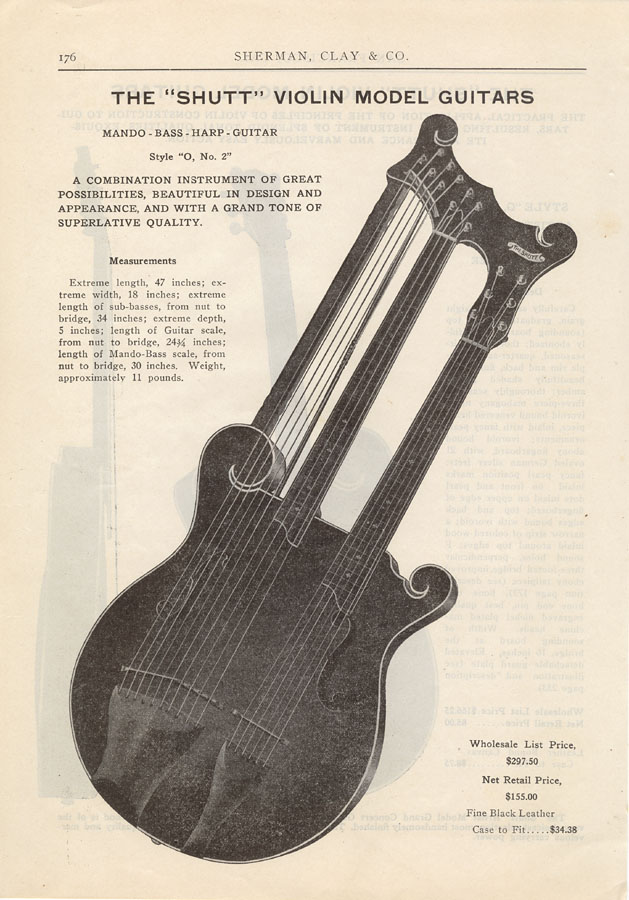

His “improvements” on the Gibson instruments culminated in the elaborate “Mando-Bass-Harp-Guitar” (right), which cleverly combined Gibson’s 10-bass harp guitar with their just-introduced giant mandobass.

Its lack of acceptance or orders – along with the fairly quick demise of his entire instrument-building enterprise – does not to me make Shutt a failure, it makes him a charmingly creative and guileless individual who dared to compete with the most popular maker of quality fretted stringed instruments of the era.

I still wish I understood why. He created a full line of Gibson-influenced mandolin orchestra instruments…and waited for the orders to come. Surely he knew he didn’t really have a chance?

And how exactly did he produce them?

Here’s a clue:

Exactly what I was thinking, Sean – thanks for reading. More passion (mine) in the full articles.

Hello Gregg.

Why? Passion and love of those instruments… Thankfully reality didn’t stop him from trying.

Thanks for a great blogg.

Best wishes. Sean