No, not exactly a “harp”-something, but a cool hollow arm American invention all the same – and a Harwood I’d never encountered before!

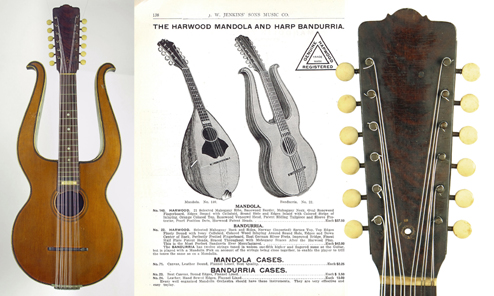

I was excited to see this wonderfully weird lyre-shaped Harwood “Harp Bandurria” in a c.1907/1908 J. W. Jenkins’ Sons catalog sold two months ago on eBay. Fortunately, the seller helped me track down the buyer, my friend Lynn Wheelright, who graciously supplied scans for us (thank you!).

Then, no sooner did I learn of the existence of this strange instrument than one showed up for sale!

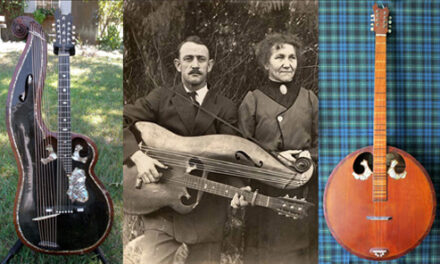

In fact, there seemed to be two – both part of a huge collection of hand-made folk stringed instruments that included a few manufacturers’ instruments, the whole lot auctioned off last month. As it turned out, another acquaintance of mine had spotted them – and so Rob Hoffman (Montaine Antiques) and I unwittingly bid against each other on the “better” instrument, which I won (above). He got the unmarked instrument (below), which I was leery about, not knowing if it was an altered, second Harwood or perhaps some homemade “folk” copy of it.

I could see that the labeled Harwood would need a lot of work, and bid accordingly (thanks Rob for making me still overpay!). I probably should’ve asked for more photos and a real condition report, but probably would’ve bid just the same as it is such a rarity and a perfect fit for the Miner Museum. Alas, although not a total basket case, it’s thrashed beyond any financially logical point of restoring at the moment. A shame, as I bet it would sound wonderful! I thought that the rattling I heard as I unpacked it was a loose brace or two, until kerfing started pouring out of it. And that neck/shoulder cave in – ouch!

Rob’s instrument had its own problems, though he was thrilled to remove the weird added fretboard to find the original Harwood fretboard underneath. He immediately wrote to see what I knew of this strange 12-string with its 17.5” scale, unaware of the recent catalog discovery. Rob (an accomplished luthier and past GAL contributor) hopes to tackle his restoration soon.

Built circa 1907, these instruments would have been built in the Jenkins Kansas City “factory” (though Rob, who has inspected many Harwoods, has his doubts). I’ll be adding more about this when I do a rewrite of my Harwood page.

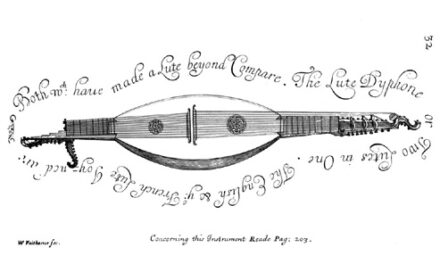

Luckily, from the catalog we knew how it was intended to be tuned − and it wasn’t as a “bandurria” as it had been named. In fact, as you’ve already noticed, it’s not even a “harp”-something, it’s a lyre-something. ( I wonder if the Jenkins folks might have possibly been influenced by an instrument patented and introduced in 1900 by Joseph Behee: a lyre guitar that he naively dubbed the “Lyric Behee Harp Guitar.”)

The Jenkins catalog states “The BANDURRIA has twelve strings tuned in unison one-fifth higher and fingered same as the Guitar, but is played with a Mandolin Pick on account of the strings being close together, to enable the player to trill the tones the same as on a Mandolin.”

Problem is, this isn’t bandurria tuning, nor close in pitch or scale. Here is the Harwood side by side with my Spanish made bandurria; the Harwood scale is 17-1/2”, the bandurria is 10-1/4”:

It’s especially strange that the Jenkins Company chose to call this a “bandurria,” as they had actually already made a true (American) bandurria, as seen above!

Normally, Spanish bandurrias are tuned in perfect fourths, starting with g# (a half step above the lowest string on a mandolin), and ending on a” (above the mandolin’s high e”).

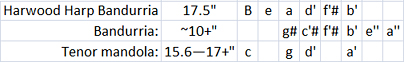

In the chart below, I show the pitches of 3 relevant instruments aligned vertically as closely as possible. A traditional bandurria is essentially an octave above the Harwood tuning. Note also how the Harwood aligns with the 4 strings of a tenor mandola, the instrument the Harwood scale is closest to.

However, it’s neither a mandolin family instrument nor a true bandurria. It’s a made up, misnamed novelty in guitar tuning up a fifth…in other words, a “lyre quint guitar”!

It’s doubtful that the previous owner(s) of these two Harwood instruments knew how to tune them – nor can we know how they did. But whatever it was, they seriously miscalculated! Rob’s – with an added support dowel through the middle of the body – was strung with heavy piano wire, while mine had super heavy nickel/steel guitar strings on it (.016-.058). And remember, they’re doubled! No way they tuned this as intended, and even at guitar pitch, it’d be pretty intense. No wonder it caved in. The hole in the head and back of the arms was from an added yoke crosspiece – a valiant but pitiful attempt to arrest the slow implosion of the otherwise delightful and presumably useful instrument.

So from zero knowledge of the existence of such an instrument or any specimens, we jump overnight to full identification and three specimens. Wait – three? Yes, an anonymous collector friend of Rob’s has had one (the best of the lot) hanging on his “wall of oddball fame” for some time.

At least now they know what it is…and isn’t!

Photographs of mine (serial #26227), Rob’s (#26219) and anonymous (#26302):

This is close to the Behee Harp Guitar. It doesn’t have the connecting dowel between the horns. I have a letter from Frank Behee describing how to tune the guitar in octaves so it sounds like 2 guitars playing. According to Uncle Frank, the dowell connection passed sounds between the horns and the horns held the sound 30% longer than a standard guitar.

https://youtu.be/Rn6Gewjdau4