Thursday, June 1, 2017: After the AMIS opening reception at Edinburgh’s St. Cecilia’s Hall (new home of the Musical Instrument Museum) then our first pub, and now tremendously jet-lagged we slept like the dead. Assuming the dead similarly jolt awake at all hours during their bedtime and have really weird dreams. So no, 12 fitful hours didn’t cut it, nor did the cafeteria coffee, which we soon learned to spike with packets of Starbucks instant to be effective.

By this time, our fellow AMISers had all disappeared, off to the first full day of back-to-back papers (20-minute presentations of new research). As my own area of interest would be covered at the end of the day, Jaci had planned a special hooky day for us: Scottish falconry!

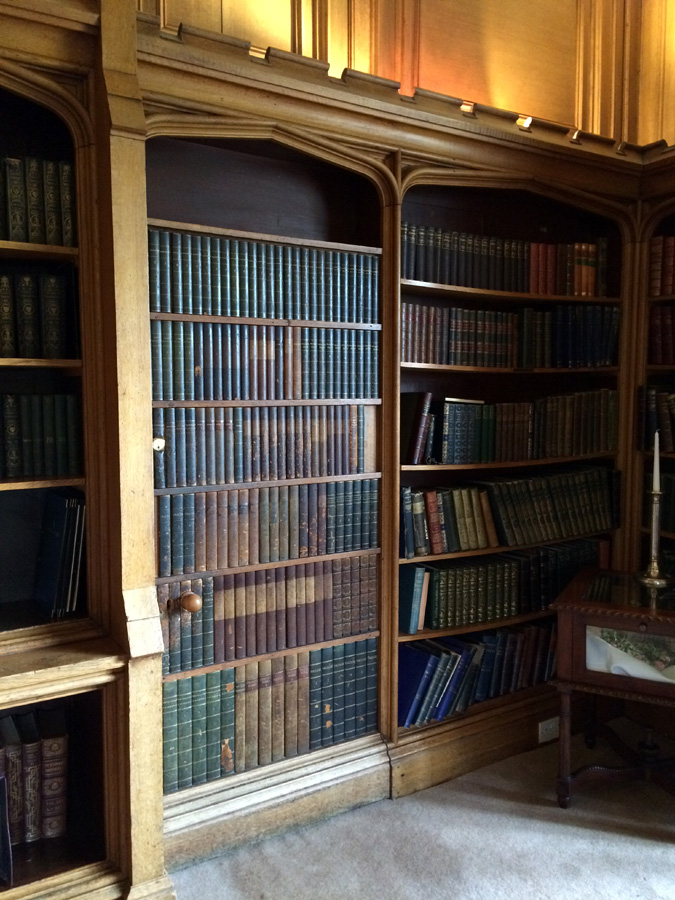

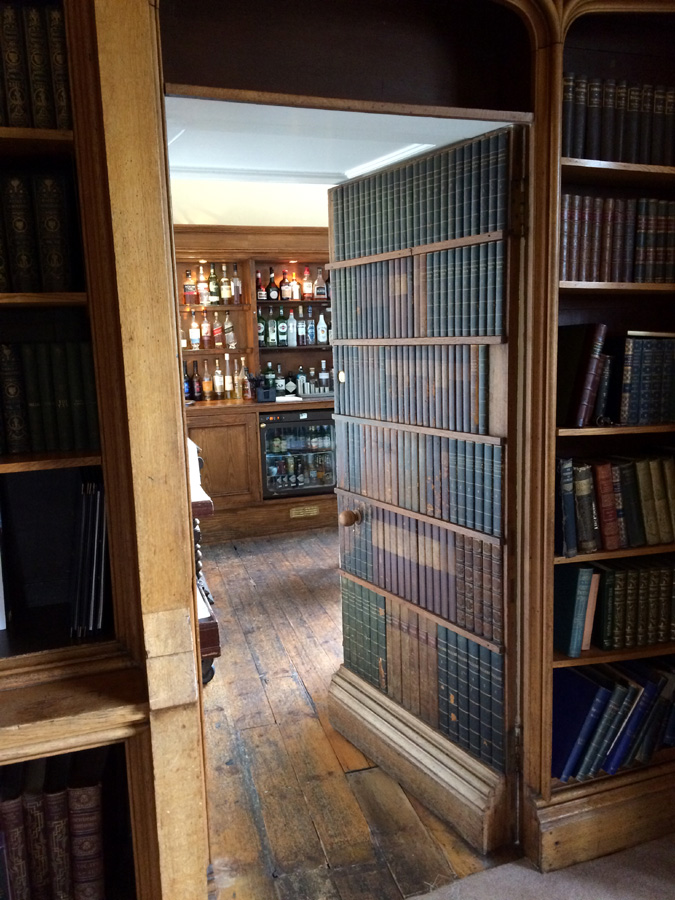

It took place a short taxi ride away at centuries-old Dalhousie Castle, now a hotel (where we wished we were staying!). As we were early for our appointment, they kindly gave us private tea in the stunning library, served out of its secret bar behind a false bookcase.

The castle has extensive grounds, a large swath of which permanently houses the falconry facilities and the birds’ airspace.

I had absolutely no idea what to expect, so traversing this gauntlet of winged death was a unique introduction.

The raptors spend their day tethered to individual perches, spread out so they don’t kill each other. It was thus cool to see them all act in tandem to vocally threaten a passing unfamiliar dog.

I had anticipated a species or two of falcons of some sort, so was delighted to find not just falcons, but all types of raptors including eagles, hawks, buzzards, and kestrels. Though not all interact with the public, each one is flown daily, at which time they’re also fed. They’d then retire for the evening into small individual sheds in complete darkness (like my wife, the only way they can get to sleep).

As exciting as all this was, I was wholly surprised and thrilled to discover that this version of falconry also employed an equal assortment of owls (which are neither raptors nor “birds of prey” but Strigiformes from a completely different lineage). I’ve been smitten with them ever since being lucky enough to work with barn owls for my early ‘70s weekly Lincoln Park Zoo Docent Chicago area school excursions. These several different species were mostly new to me.

Like you, we asked, “But aren’t owls nocturnal?” Yes and no. These species were mostly crepuscular (dusk and dawn) hunters, and perfectly comfortable with daytime activity.

For our first session, the short straw was drawn by a huge Turkmenistan Eagle Owl named “Duke” (he walks like John Wayne, as you’ll see in the video).

Photos can’t do justice to the subtleties and gorgeousness of the plumage, nor the huge eyes with their mesmerizing 3-dimensional depth.

We managed a few snippets of video:

We managed a few snippets of video:

The trainer Georgie told us how intelligent raptors were but how dumb owls were. Yet watch its doglike attention after landing on the ground. It’s clearly making eye contact with her and reacting to (and obeying) her instructions. Then I pass my iPhone to Jaci as she hands me the glove. Duke was huge but weighed just 4.9 pounds. We were surprised to hear that he was 30 years old, (close to the max lifespan), as were many of the birds. They’re acquired from various hobbyist breeders and hand-raised from a week old (owls) or ~6 weeks old (raptors).

We were allowed to pet the owls, which they tolerated with aplomb. Afterward, our friend Jaymee (BMFA curator) was so inspired by our video that she booked her own session that week; she was able to literally cuddle her similar eagle owl. Precious!

For the “raptor” segment of our double bill, Georgie chose a Harris’ hawk. Though she could commune nose-to-razor-sharp beak with it, we were advised not to try to touch it. Whereas the owl flew from a low perch or the ground, upon release the hawk promptly disappeared into the nether regions of the surrounding trees. I was told to hold tight to my “prey item” (a little thawed chick), and sure enough, I was soon dive-bombed via an extremely rude, attempted “snatch and grab” fly by. That happened about three times until the tough guy’s exuberance wore off and it realized I was no pushover. We were soon best friends, or so I tried to assure myself through its intelligent, malevolent penetrating stare (hey, they can’t help it – it’s just a protective bony ridge above their eyes).

Jaci and I were blown away by this tiny but imposing ex-dinosaur. We’re hooked.

The hawk is “mantling” as he gets the rest of his daily protein from the trainer; this is an instinctive behavior to keep other predators away. I certainly wasn’t going near him.

This sweet little guy is a week-old little owl, a rescued local. It charmingly performed a full Linda Blair Exorcist 180 for me as I was allowed to stroke it.

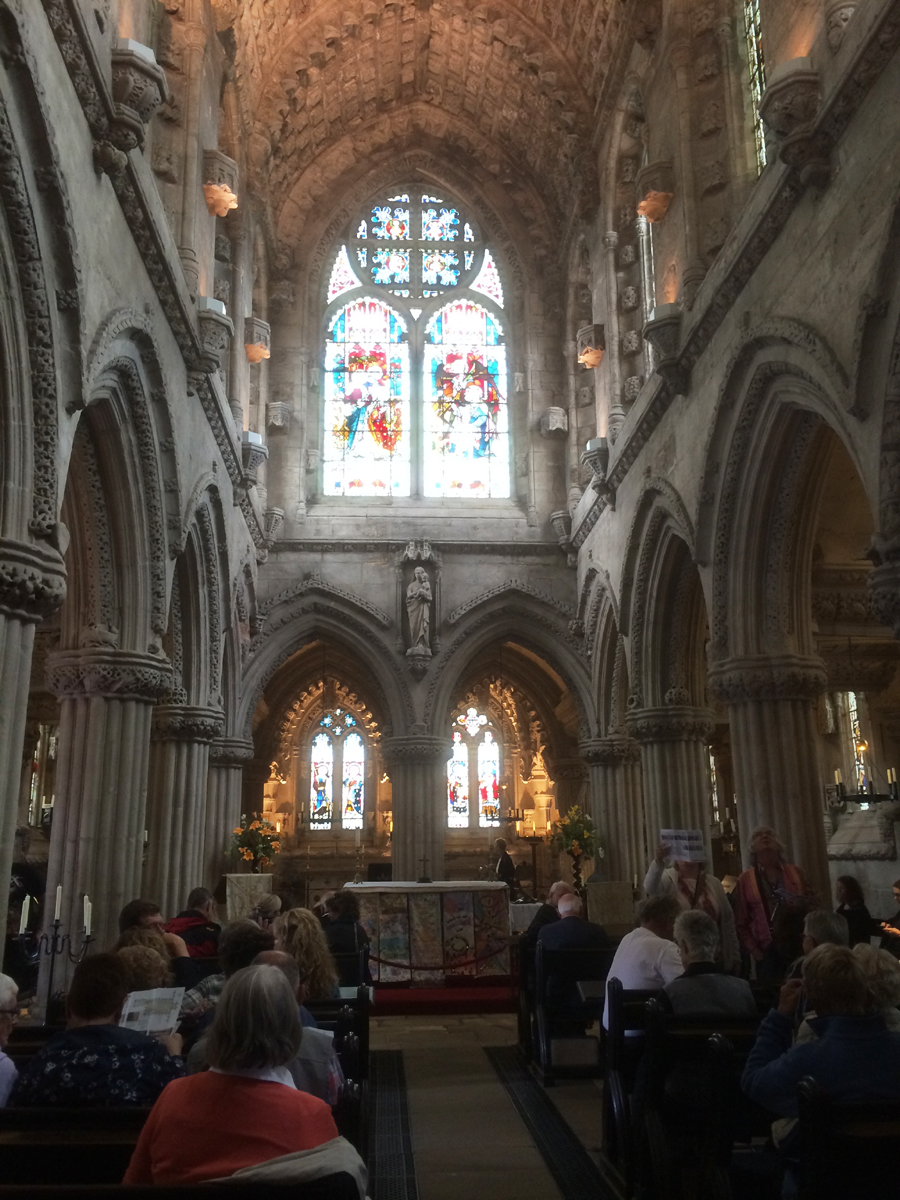

Though loathe to leave our new feathered friends, our time was up. As we were close by, we hopped in a cab and headed out a bit further to Rosslyn Chapel.

An ancient, weathered 15th-century historical site, it’s now a tourist attraction thanks to the Da Vinci Code book and film.

If there were any clues Robert Langdon missed, we couldn’t find them.

Pictures inside were not allowed; we snuck a couple.

Getting directions to a nearby bus back to Edinburgh, we got back just in time for the late afternoon papers I hoped to see.

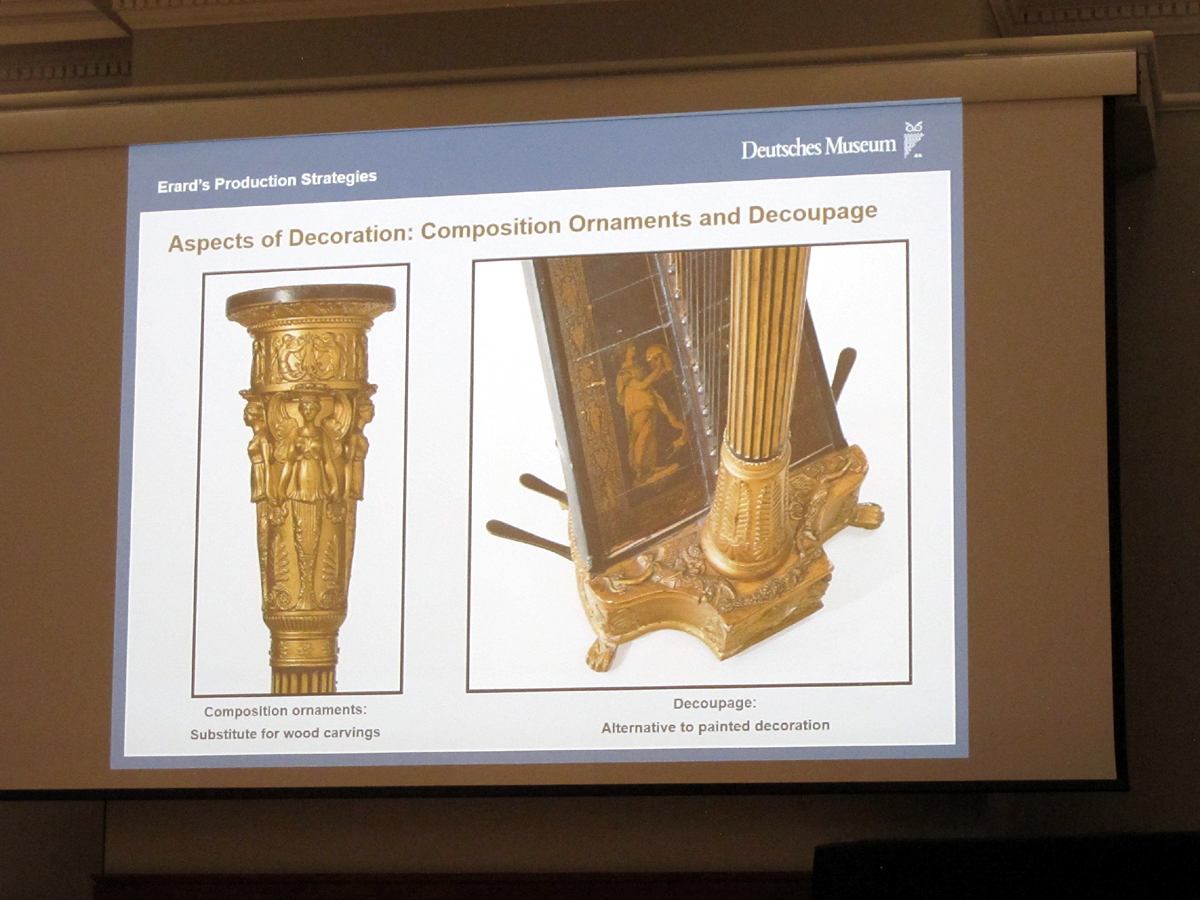

First up was Panois Poulopoulos, who had done a study on Erard harp production. He mentioned the gilt decoupage soundboard decoration and mentioned outside firms that specialized in the work. I’m still hoping someone can walk me through the specifics of the whole procedure, as this is obviously the semi-mass-producible technique for all the Edward Light harp-lutes and similar “spectacular from a distance” instruments I hold dear.

Karen Loomis from the States explained her fascinating experiment to string her Welsh bray harp with horsehair strings, complete with a sound sample comparison. I was unaware (as were many) that there were early sources mentioning hair strings – unfortunately without details or the ancient techniques, which she was able to re-engineer. Impressive!

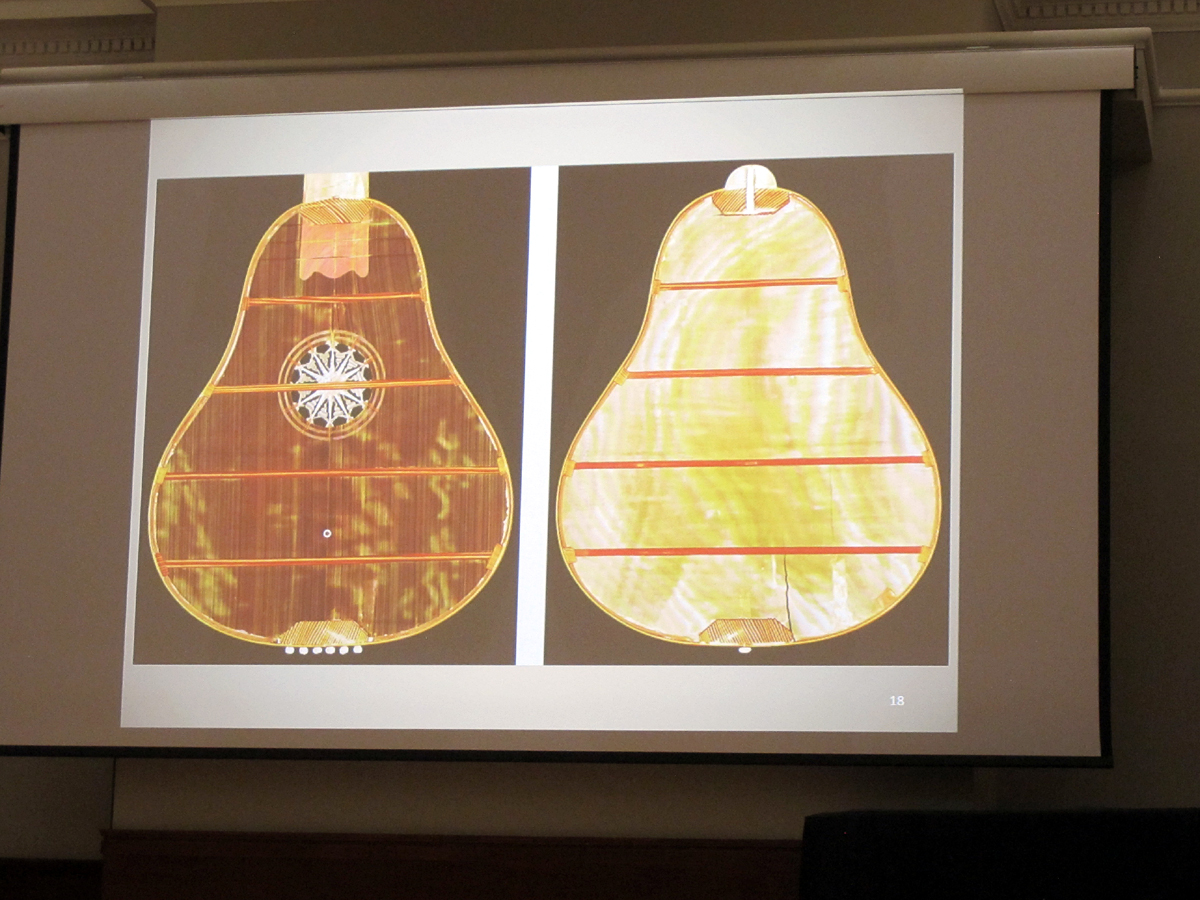

Geerten Verberkmoes from Ghent, Belgium showed analysis of a rare Dutch guittar, demonstrating its surprisingly early appearance in the Netherlands. (And people are still calling it the “English Guitar”…)

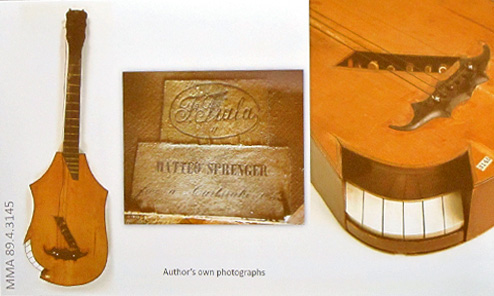

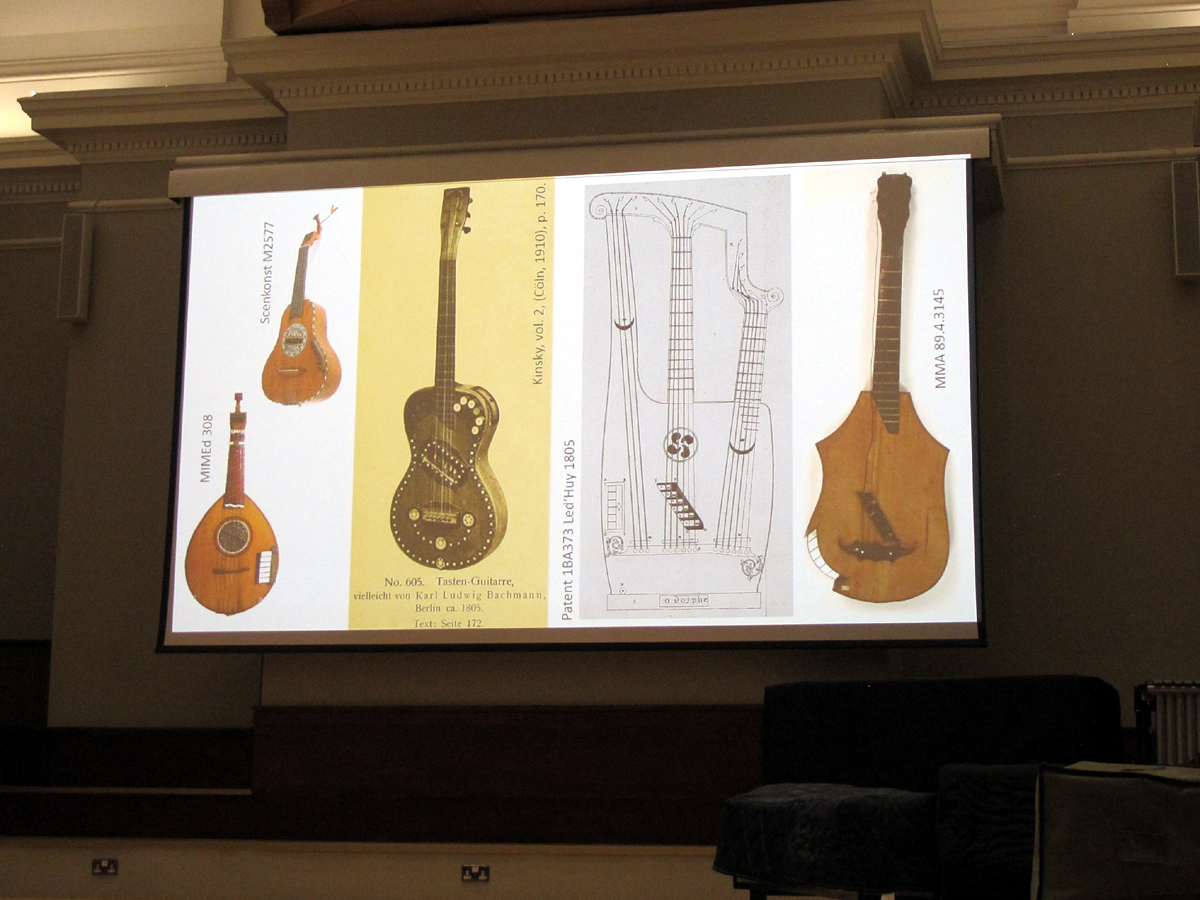

As I am to harp guitars, so is Daniel Wheeldon to keyed guitars (well, somebody’s got to!). In New York, 2012, where I first met him, he spoke of the keyed guittar (aka “English guitar”), and his obsession has now taken him to Tastenguitarre of the standard 6-string variety.

While doing a year string at the Met Museum, he was able to study a rare never-exhibited German specimen. His paper was intended to compare this to the only other surviving specimen, but even as his PowerPoint was drying he learned of a third, just discovered by our old German collector friend, Rainer Krause! His goal is to build a working reproduction, and I am holding him to it!

Papers over for the day, Jaci and I went out to dinner with friends (fish & chips, but really good fish & chips). Afterward, everyone gathered back at the hall after for music and dancing to a ‘20s jazz band. I fell asleep despite the cacophony, and don’t remember getting home…and tomorrow was another busy day.

Hi Gregg.Thanks for the blogg, just love the keyed guitars, never noticed those before. Best wishes.