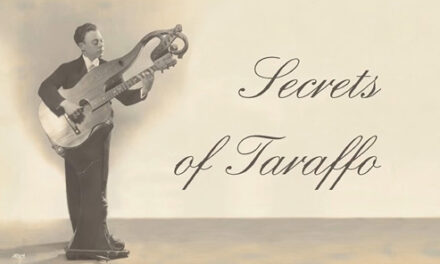

Readers new to my site and blog may have missed a rather critical distinction I pointed out some years ago in this article: What a Harp Guitar Isn’t.

Since people invariably confuse the issue, I reminded all that these instruments are actually “zither-guitars” in configuration, rather than “harp” guitars. Ironic, I know.

Thus, one of the extremely few “technically correct” “harp-guitars” therefore is Alan Carruth’s 2010 experiment:

You see it, right? … the sub-basses are attached perpendicularly to a miniature harp soundbox!

Having just done a big Facebook post on my harps, I thought the above would introduce this otherwise-unrelated topic here nicely. It never hurts to see more examples of harp configuration. And, so:

In other Miner Museum news…this happened.

When I’m not in there myself, I keep the Museum room locked up – which must be when these damn things are apparently breeding in there. I’ve had some recent questions about new objects in the museum, so now’s a good time to group these together for some show and tell.

Having recently shed my harp-guitar-playing acrylics to get back to another love (my modern harps out in the living room), the Miner Museum has similarly seen a serendipitous shift into that world. These are not quite yet playable (and one will never be). Let’s take a look!

The c.1915 New York Clark Irish harp is a direct replacement (color, etc.) of the one I played on A Christmas Collection and at my holiday shows until its neck separated (at a previous repair line). It’s still a favorite design and decorative piece to me. We classify all these gut/nylon-string instruments as “neo-Irish harps” – the original Scotland/Ireland harps being wire-strung with completely different body construction and physics. (“Neo” in this case means “new/revived/modified.”) The Clark specifically emulated (essentially copied) the original “neo” invention, the early 1800s Egan “Portable Irish Harp.” (Get my friend Nancy Hurrell’s wonderful new book on this subject!)

Next: an actual Irish neo-Irish harp, from Belfast. An early 1900s James McFall harp. While Clarks are fairly common, these I learned are quite rare. Also inspired by the Egan and the new revival, McFall’s design is his own, and quite wonderful (the Salvi Harp Co. loves it as well – they built a modern copy). On some, the Celtic knotwork is a decoupage decal, like on the Clark. On others like this one, the artwork is hand-colored within recessed lines carved into the soundboard. I was anxious to fix its loose neck joint and re-string it to see what it sounds like – until I got a look at the crude, heavy soundboard cross braces. Alas, I’m not expecting anything too magical.

Circa 1780 single-action pedal harp from Cousineau Pere et Fils a Paris (“father and son,” Georges & Jacques-Georges, respectively). It was affordable as it’s worm-eaten, not in fabulous shape and missing some hardware, but still plenty presentable. And let’s face it, I’m still pretty light on pre-1800 instruments. Plus, after her first Naderman, harp-playing queen Marie Antoinette apparently preferred the Cousineaus.

I touched up some joints and the soundboard, then replaced the glass in the clever see-through piece for the neck mechanics. I love the vaguely-Steampunk silhouette brasswork. They included different designs in the oval window; Jaci and I love that this one features a dog! (below right)

While all others’ single-pedal mechanism had crochet (hook) mechanisms, Cousineau had just introduced his “double crutch” system. For each pedal, two tabs swing in from either side to pinch and “fret” the string. For reasons unknown, the second set of crutch-shaped “nuts” was removed from the shafts on mine; perhaps due to warping/movement over time this corrected intonation and buzzing.

Bucket list time. Long ago, I knew of this from my harp history books – the Pleyel & Lyon cross-strung harp (circa 1900, Paris). This was the first one I saw…in 2004 in London in museum-dealer Tony Bingham’s office. Was simply out of my league, as were the couple others I saw over the years. Luckily, pretty much all the key museums have one, so this one (perhaps my favorite of the many different styles) hadn’t gone anywhere. Last year, everything just sort of fell into place (the pound was at its lowest ever – thank you, Brexit!), and last summer, thanks to Tony and staff, a giant 300 pound crate landed on my stoop.

Splay your fingers and interlace them. On the right are the naturals (the white keys on the piano). On the left, the black keys/accidentals. Fully chromatic without pedals, simple! A few dedicated musicians (in Belgium, mostly) still actually play these. Will I? Well, I gotta try! First have to deal with some missing (custom) strings.

This was a serious instrument, meant to sway orchestral players. At this critical juncture, it was either the already-common double-action pedal harp…or this. For the momentous occasion, they commissioned Debussy himself, who composed his Danses Sacrée et Profane for this very instrument.

He lost. (Though the fantastic piece endures on pedal harp today.)

Ok, let’s head out to the living room.

About 1998, I decided to finally up-size my smaller Style 17 Lyon & Healy harp. That was the one that I bought used in Chicago with my small life savings the week before I relocated to California (the trunk just cleared my van’s doors). It closed my A Christmas Collection Volume 1.

I sprung for this 1960s full-size Style 23-Gold (it was mainly for more right hand spacing). The gold 23 is essentially the big brother to the Style 17 (1 more string, a couple inches taller, heavier, and with the entire column gilded).

I quite like some of the other popular L&H harps, like the more prestigious Style 11 or the wild Art Deco Salzedo model – but if I had to choose one professional pedal harp (and I do), it has to be this one.

It is purely an aesthetic choice, and (honestly!) has nothing to do with the fact that this was also the model Harpo Marx owned and played in every movie from Animal Crackers to The Big Store.

Above: From yet another of my collections: Harpo with his Style 23-G in his Beverly Hills backyard getting a lesson from Mildred Dilling.

Below: Yours truly, age 24, getting his first (unplanned) lesson from Ms. Dilling in 1979.

During the lunch break for the master class she was giving, she walked me down a few Chicago blocks to an office building to introduce me to an ex-student who happened to have a used harp for sale. That was the Style 17 mentioned above. I cashed in my life savings ($3250) and bought it on the spot.

Upon purchase of the new 23-G, I had it shipped to L&H in Chicago and back for a full overhaul, after which I soon sadly mothballed it (choosing to concentrate on steel-string harp guitars – necessitating acrylic nails – once I saw my future with the Harp Guitar Gatherings and those musicians).

I’m happy to report it’s now out of mothballs, and I just had it serviced by L&H harp tech Jason Azem during his Southern Cal visit (interesting, albeit unnerving, how much things had shifted, even without being played or moved).

I now find myself strongly reminded of what an improbable, impractical, yet ingenious and impressive instrument is the modern orchestral harp.

The Triplett Celtic I is an original 1980s nylon-string “Celtic” model, before it was slightly redesigned. Before I bought it secondhand in the late 1990s (to replace the fragile Clark), the seller let me take it to the old Sylvia Woods harp center in Glendale, where they let me A/B/C it with the full line of then-available modern harps. There, I found the best new instrument (to my ears) to be a Dusty Strings bubinga…but this blew it away. Sounds closer to a shimmery steel-string harp in the top register, with great bass as well (rarely achieved in these instruments).

The wonderful-sounding little 1983 Markwood wire-strung harp was what I should’ve been playing all those years with acrylics! (I just didn’t have the time or wherewithal.)

Which brings us back to the harp guitar…or does it?