We were thrilled when the esteemed Dr. Brian Torosian accepted our invitation to present a unique series of performances and workshops at the Gathering this year. I was anxious for exposure to his particular expertise: historical music written for the 8-, 9- and 10-string guitar, with J. K. Mertz’ repertoire a specialty.

It still boggles my mind how obscure this music and performance practice is. Consider the endless thousands of professional and amateur classical guitarists across the globe. Narrow that to the “early romantic” guitar (long before Segovia laid down the law), and there are still hundreds (thousands?) of players, scholars and aficionados. Then consider how common and popular the 10-string and other early “harp guitars” were during this time – many of the virtuosos played and wrote for them. Yet I can count on one hand (well, no more than 2 hands) how many serious guitarists bother to explore this repertoire on the actual instrument.

Brian is one of those, and the first virtuoso I have heard authentically performing this music. (Dennis Cinelli, who also performs Mertz on 10-string, was scheduled for HGG5, but missed it due to a family emergency) I could have listened to Brian all day – both the music and the history – as he truly shows us a window into our harp guitar past.

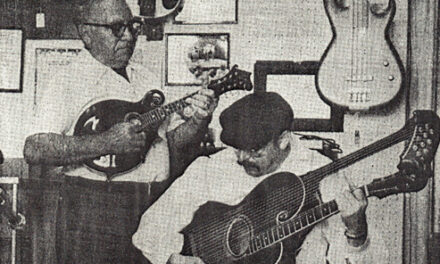

His instrument is a marvelous 10-string Scherzer reproduction built by fellow Chicagoan R. E. Brune, who had one of the surviving instruments in his repair shop. This is the infamous model said to have won the instrument competition held by Makarov in 1856. (However, Brian seems more inclined to believe that the prize-winner may have in fact been a nine-string…more on this when I convince him to spill his guts and go on record with an article for us) Below, Brian explains the 2nd “floating back,” added to preserve the resonance of the body.

Brian’s notes on the different players and composers were fascinating: Mertz, Makarov, Dubez, Bayer and more – especially how Mertz-fan Makarov freely borrowed (stole?) Mertz motifs for his own “compositions.” Most importantly, Brian’s discourse on the tricky analysis and interpretation of the music was invaluable, and another in-depth article we must ask him to write. Examples included: fretting with the thumb (common), notating the sub-bass with an 8va usually but not necessarily always, deducing how many basses were needed and/or actually used for a given piece, and even one example (performed in concert) of tuning the C to C# on the fly!

The highlight was probably the stunning Eduard Bayer 10-string solo Souvenir d’amour (Fantaisie Brillante), Op.22. Of all the multi-string music Brian has researched (most? All?) he said that this piece featured the most extensive use of the basses he has found (and very interesting use at that!). Brian went over some of the intricate techniques in our Sub-Bass Muting workshop on Sunday in more detail – techniques that are not notated in the rare scores.

I picked up Brian’s edition of Mertz’ Opern-Revue, Op. 8, Nos 9-16 and enjoyed the lengthy historical introductory chapters.

All in all, Brian proved a fascinating Gathering participant and a well-received change of pace from the army of Dyer players and other modern instruments. He seemed to thoroughly enjoy himself as well.

If you’re in the Chicago area, watch Brian’s web site for details on performances. He mentioned a major February concert he is giving, and my whole family (who were blown away by him) is going.

I very much hope to see Brian again myself someday, and yes, we’re all bugging him to record these rare works!

Prof. Brian is wonderful. I truly miss his presentations at NEIU stage and would love to attend his future performances, despite being far away. His performance is outstanding, while very relaxing and blows away the audience. By the way, I still own his book on classic guitar and I am proud to have been one of his students at NEIU several years ago.

Nice! I had to go looking for pictures of Scherzer guitars. That guitar is way too neat to be ignored, specially the back. It looks like there are air ways around it. Is that so?

Anyway, thanks for the cool blog!