Boston, Day 1 & 2

After nine days in Europe – our Genoa stay, then three days in Mulhouse – I had finally recovered from the jet lag…just in time to now head back to the States. Oh well, at least I was largely awake for this next leg. I was stopping off in Boston for the annual AMIS (American Musical Instrument Society) meeting, a mini-convention for museum curators and other instrument scholars from around the world. I would be giving a paper on the harp guitars of the Museum of Fine Arts. I know – “paper” is a weird term, as it’s all PowerPoint and narration, and in this case, also demonstration and performance.

It was now Monday, June 1st. Having a couple of days to kill and with no place to stay (our college dorm rooms wouldn’t be accessible for two more nights), my friend Steve Silva took pity on me. He, his wife Nancy and son Cory took excellent care of me for the next couple days and nights. It was like a resort, albeit an extremely thin resort.

Here we are in the backyard of their home – that’s Steve and none other than Frank Doucette, who had driven down from his new home in Vermont to hang with us. In a curious twist, this was originally Frank’s house when he lived in Boston many years ago. He sold it to the Silvas when he moved to Los Angeles, and Steve’s subsequently done some extensive remodeling, though not, apparently, making it any wider. Inside, I think it was just 12 feet across…everywhere! But with three stories, and their clever use of space (and the top floor’s guitar room opening into the high living room), it was more than ample, and quite adorable.

The next day, we spent some time in Steve’s guitar room. Here he is with his new Pellerin that I mentioned three blogs ago. This one is made with flamed Makore back and sides, which not only looks gorgeous but turns out to have a perfect tone for harp guitars.

I asked Steve to set up his ingenious string tension tester, so I could admire his handiwork and also do some new tests of nylon super-trebles for Jon Pickard.

On Tuesday afternoon, Frank, Steve and I headed over to the MFA so I could check out the three harp guitars I was expected to play.

We were greeted by my old friend Michael Suing, who once was on the MFA staff and was back to help, along with the amazing Jayme Kurland. In charge of the whole affair was curator Darcy Kuronen (at left), who is a keyboard and woodwinds guy, but ironically became known as the museum community’s “guitar guy” after putting on the “Dangerous Curves” exhibit and authoring the well-known book of the same name.

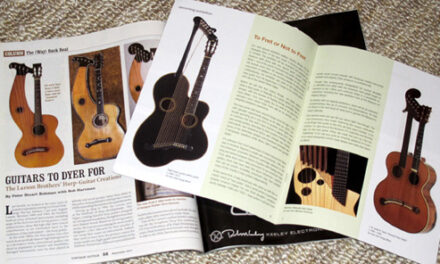

First up was to re-string their Dyer with the sub-bass set I had sent them. This went off without any mishaps (fortunately, the holes in the tuner posts were of sufficient size for once), and the original friction tuners held my light gauge set in pretty good tune. This was a nice, early five-bass Style 5 (no label) that Darcy acquired from Fred Oster. Its only issue was the severely undulating top above the bass side of the bridge. Despite this, the all-original instrument, still with its original frets and fret-wire saddle, intonated and played like a dream. Even better, it sounded spectacular – literally as good as these instruments can sound, a true 10 out of 10.

One down!

The very clean c.1919 Gibson, which neither Darcy nor I had any strings for, was a bit of a mess…at least if I hoped to play it.

The subs were old and pretty dead but would be fine for demonstrating the unique chromatic tuning. The neck strings were OK, except the first and second sounded strangely scratchy on my acrylics. And here’s when I discovered a first-time-ever interesting observation on early Gibson instruments.

I’ve seen plenty of Gibson harp guitars stored in original cases for decades with no ill effects, so this was a new aberration. The still-newish strings – specifically the first, and diminishing after the 2nd – had completely corroded with a thick layer of white oxidation (?) – but only at the 8-10” section adjacent to the celluloid pickguard. Clearly, the pickguard must be outgassing – nothing as bad as those D’Angelico jazz guitars, but probably a similar situation. It showed what looked like subtle splotches of super-fine dust – but they didn’t wipe off. It seemed more like micro-pitting from a chemical change; Steve Silva thought it went down into the celluloid as well. The museum will now have to store the harp guitar in a separate acid-free archival box and store the case separately – something I hope all Gibson owners won’t have to do! Perhaps this c.1919-1920 harp guitar’s pickguard came from a different batch or supplier of celluloid?

We steel-wooled the string corrosion and tuned it up. I had worked up a bit of Stephen Bennett’s “Down by the Old Mill Stream” with some clever use of Gibson’s chromatic basses, but I should’ve prepared a first position-only arrangement! The intonation was out by a mile. Not an uncommon problem, and Darcy OK’d me moving the bridge, which I was not excited about doing as it involves de-tuning and re-tuning 16 strings and we hadn’t much time! Above you see me only partially pretending how difficult this tweak was, especially on a near-mint top of a valuable MFA instrument. I made just one attempt, and it improved some, but not enough to make good music. Then there’s the design flaw where the outer basses angle much more at the bridge than the neck strings do, so they want to shove the whole bank of strings off-center. The high E string was thus almost impossible to keep on the neck while fretting anywhere up a ways! Oh, and the pickguard had lost its pin that fits into a hole in the bridge, so kept falling off; we finally just removed it completely for playing.

Oh well, I’d just have to make do!

Ah, but when I got to the Mozzani, everything changed. Here was an absolute dream harp guitar. This also came from Fred Oster (originally Music Treasures in Canada), and had I known what I knew now with it in hand, I would’ve definitely tried to acquire it. It was very different from my (now two) Mozzanis, which are huge, double-arm models. This one sounded very sweet and was a joy to play. A large part probably came from the fact that it was quite small, with a lower bout width of just 15-3/4” and a scale of 595mm (less than 23-1/2”). Was it built as a terz harp guitar? If you’ve read the new Mozzani book, you know that’s not a straightforward answer. I assume this one was strung with standard classical guitar strings, as they begged to be tuned higher and were exceedingly light to the touch. Still, at less than 3” deep, it put out an amazing sound!

Frank was apparently being clever, creatively tilting my camera. I don’t know which way this is supposed to go! (click for 90 version)

Ah, you noticed that someone drilled an unsightly hole in the top…I’ll let you think about it, and address this in the next issue (there’s more than meets the eye).

Darcy didn’t have time or means to show us any off-exhibit museum treasures, but as these two were sitting in their cases on the shelf right behind us, he got them out – he was understandably proud to show them off! As absolutely presentation-grade as I’ve ever seen on an American parlor guitar. The Tilton on the left was amazing, but the Bay State on the right was simply breathtaking.

The design of pearl and shell inlaid into the sides around the neck was exquisite. But that’s in an area that is easily seen…

…who checks out the endpin? An equally incredible and beautiful design. I would kill (Darcy) for this guitar!

Steve is pointing at the ridiculously tiny and meticulous “checkerboard” purfling strip that bordered every bit of binding everywhere – rosette, body, fingerboard. This guitar was tasteful while giving new meaning to the term “festooned.”

I’m re-experiencing complete visual overload just typing these captions…I imagine you are, too. So I think I’ll stop this issue right here.