One hundred and two years, to be precise.

The story:

In 1988, I bought a copy of the Third Edition Martin book by the late Mike Longsworth. Amidst all the expected guitars and ukuleles there was on page 214 this curious black and white photo of a very unusual lyre-shaped guitar – something completely bizarre and unknown to me at the time.

The text explained how one Dr. Robert Sands shipped his “Dubetz model harp guitar” to the Martin factory in October, 1912 to have them build him an improved reproduction. Longsworth’s information came from correspondence letters between Sands and Frank H. Martin that were found with the surviving original instrument that had been stored for decades in Martin’s North Street plant’s attic. The pieced-together information tells how Dubetz himself allegedly sold the instrument to Dr. Sands. I explore this (and Dubetz/Dubez) fully in my previous blog on the instrument.

In the fall of 2011 I was thrilled to learn that the original Sands instrument was on display in the Martin museum, after receiving these photos from my friend Joe Morgan.

Curiously, neither Longsworth nor the current museum curators thought to mention the “European builder” of the remarkable original instrument, who is of course Friedrich Schenk, pupil of J. G. Staufer and one of the most significant harp guitar creators known today. The coincidence (irony?) of this Martin-Schenk connection (both worked under Staufer) is surely one worth noting!

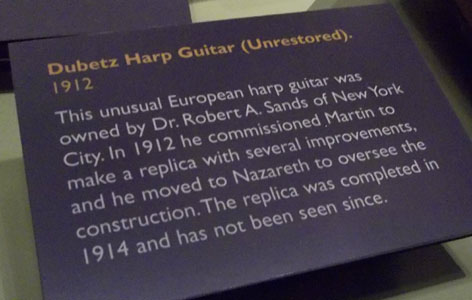

The sign in the Martin museum states that the “replica was completed in 1914 and has not been seen since.” In my previous post, I lamented this fact and expressed surprise at how such a distinctive project by this most famous guitar manufacturer could have just vanished.

Well, just last week I discovered that it had been hiding just off the beaten path for many long years! Its trail remains unknown, but at some point it passed from Dr. Sands’ hands to an intermediary or two and finally wound up in the hands of Henry Goldrich, the second generation proprietor of Manny’s Music, onetime legendary New York music store. It’s not known if Manny himself had originally acquired it. From its home on a wall of H. Goldrich’s home, it was then passed down to the third generation, Manny’s grandson, Ian Goldrich (current manager of the Manhattan location of Sam Ash Stores, who bought out Manny’s in 1999).

Ian has no current plans to get rid of it, but it would be well worth someone (from Martin, perhaps?) asking to inspect and document this fascinating specimen.

According to the records, Martin delivered Dr. Sands’ “reproduction” in 1914. The requested improvements included more room for the wrist and “thumb action on the neck up to the 17th fret” with “as many strings as practical to the harp portion, 16 more if possible.”

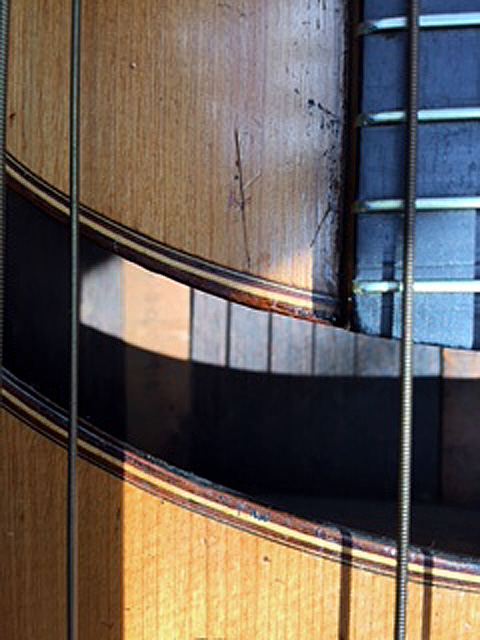

Italics are mine – I had always wondered how many sub-bass strings they managed to cram onto it (Schenk’s only had four). It looks like they settled on eleven, for a full chromatic scale (counting the neck’s E string). It was unfortunately altered somewhere along the way – that’s an obvious pickguard addition and rather ill-advised bridge replacement, which subsequently reduced the bass number to eight. I’d like to think that the original bridge was more reminiscent of Schenk’s Viennese design. Those goofy jazz age fretboard markers don’t exactly fit the Schenk vibe either!

It’s interesting to finally be able to compare the two. Ignoring the specific dimensions for the moment, it looks like Martin copied the body outline very closely, and even copied that same bizarre soundhole that all but bisects the top. They (or Sands) chose to omit the two “flower tip” arm soundholes and the circular headstock opening. Again, pending precise measurements, it appears that Sands requested the same short scale length of just 20”. At roughly 510mm, this is an extremely short terz scale (tuned a third higher), even for Schenk, who appears to have intended his double-arm “lyra-gitarres” as terz instruments.

It doesn’t appear that they gave Sands his “thumb action” to the 17th fret; the body on that side meets around the 11th/12th like Schenk’s.

The tuners – which could certainly all be original – appear to be friction tuners for the neck strings and Gibson’s sub-bass key type for the subs. They kept the same depth as the side walls for this entire head section, necessitating deep routed holes for all the tuners. Curiously, there are six extra non-routed holes that go all the way through (two of them plugged); I have no idea what someone was attempting there! It’s now strung with steel, though I wonder if that’s what was intended.

Nice Brazilian back and binding – what a wonderful instrument this must have been when new.

Thanks to Ian for sharing this incredible piece of harp guitar history!

UPDATE: While at the Martin Museum during my AMIS trip, Dick informed me that two of these instruments were made…so, hope of finding the other?!

That would be a good excuse to plan another trip to the Martin Museum.

Wow. I can’t believe you finally located this thing. Interesting to see the differences between the original and the reproduction. I would love to have seen it with the original bridge and fingerboard and without the pickguard. You never cease to amaze, Sir Gregg.

Thanks, Joe – but I didn’t find it, it found me. He did also contact Martin. Dick Boak tells me they’re now going to restore the Schenck and plan to eventually photograph the two side by side!